On the outskirts of Langley City, thousands of writhing maggots are fed by conveyor belt into a kiln-like dryer, emerging half-baked and lifeless on the other side.

This drying room is part of a sprawling 5,600-square-metre commercial insect farm, one of the world’s first. In the span of minutes, these black soldier fly larvae have become nutritious, high-protein food that chickens, dogs, cats and farmed Atlantic salmon love to eat.

“This is the future of food,” says Bruce Jowett, director of marketing for Enterra, a private B.C. company that sells farmed fly larvae products directly to commercial feed companies. “We are diverting food waste from the landfill, and black soldier fly larvae are converting it into protein.”

My visit to this facility took weeks to arrange, and frankly, I wasn’t looking forward to it. That’s because every encounter I’ve ever had with maggots came with a vomit-inducing smell attached. But the faint scent of peanuts wafting around the cooking room was a surprise — and seemed to signal that these creepy crawlies had gone from gross-outs to real food.

Enterra’s larvae (Jowett prefers this term to “maggots”) are technically livestock, making this, by population, one of the largest animal husbandry operations in the world — part of an early-stage farming experiment that is already making the world’s biggest feed producers take notice.

In recent years, the $400-billion annual global animal feed market has grown hungry for alternatives to wild fish and soybeans — currently two dominant animal feed protein sources.

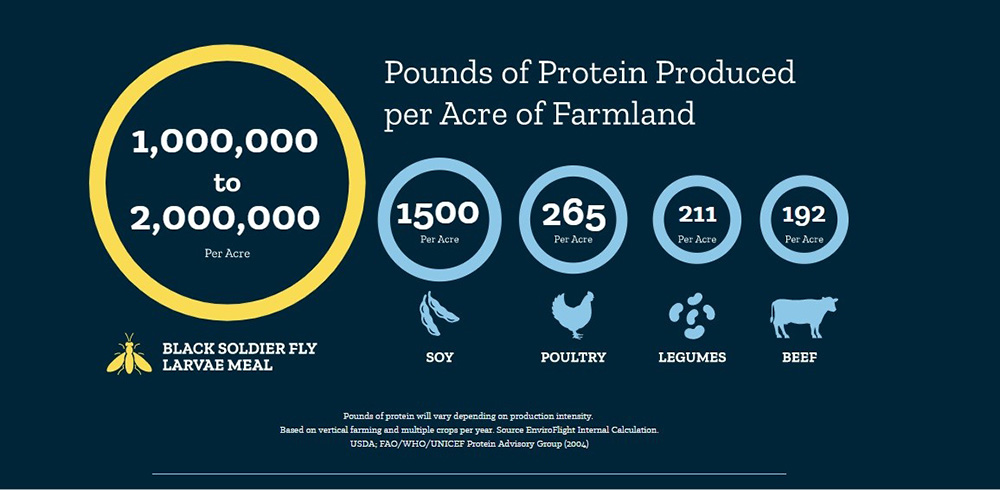

About one-quarter of the world’s entire commercial fish catch — mostly forage fishes like herring, menhaden and anchoveta — are reduced into protein meal and oil for livestock and aquaculture. Meanwhile soybeans consume vast tracts of forests and land, relying on herbicides and other chemicals.

Enter the black soldier fly, a quick-to-mature, non-invasive insect that has a voracious appetite during its larval stages. In Langley City, they thrive on a diet of 100 per cent pre-consumer food waste, diverting otherwise unsaleable food from local landfills. Jowett says the operation requires no water, a miniscule footprint of land, with negligible methane or greenhouse gas emissions.

Our visit to Langley in early June comes at a critical moment for the fledgling insect agriculture industry: companies like Enterra must now demonstrate that insects can be farmed on a commercial scale, capable of satisfying the world’s growing appetite for chickens, farmed seafood and pets.

As of this writing, Enterra and at least five other fledgling bug agriculture companies around the world are at various early stages of commercial readiness. This summer, Enterra will open its new $30-million, 17,000-square-metre insect farm north of Calgary, with new farms coming to Greater Vancouver and Ohio in the next five years.

Jowett says Enterra will soon be ready to supply its sustainable bugs to a protein-hungry world. But is the world ready to embrace farmed bug larvae?

Enterra was founded in 2007 with a vision of reducing the reliance on wild fish protein fed to Atlantic salmon in fish farms.

The company was born after a series of conversations between founding CEO Brad Marchant and environmentalist David Suzuki.

As Suzuki tells it by email, he met Marchant by chance on a Yukon rafting trip. “Brad listened to me bitching about farming carnivores like Atlantic salmon. I was saying that since salmon live in freshwater in their early lives and eat insects, [that] should be fine in fish food.”

Marchant liked the idea, hired a scientist to find the right insect, and sent Suzuki shares in the company for coming up with the idea. Suzuki donated those shares to his foundation, and later invested in the company.

By 2014 Enterra moved to the Langley site, where the production system was designed by trial and error, converting a greenhouse complex into one of the world’s first bug livestock farms. Enterra says Marchant retired as CEO in 2016.

Walking around the site with Jowett and vice-president of operations Victoria Leung in early June, secrecy is tight. That’s because bug farming at this stage is cutthroat. Everything in this plant has been designed from scratch, much is proprietary. Not only did photographer Christopher Cheung and I have to sign non-disclosure agreements to get onto the property, Leung at one point asked Cheung to delete a photo that showed the details of one of the machines on the site. Lessons gleaned here are being applied to the new Calgary farm, which at 17,000 square metres, is three times this size.

An insect farm like this must continually breed new bugs, grow them to maturity, and turn the bodies into saleable feed products. To that end, Enterra produces three end products: whole dried “grubs” which are popular as wild bird feeder and pet fish food; a ground protein-rich powder or “meal” ideal for aquaculture; and a fatty oil, created by pressing the dried bugs, which is typically applied to animal feed as a coating.

Our first visit is a warehouse building Leung calls “the love shack” — where adult black soldier flies reproduce and the females lay up to 600 eggs at a time. About 99 per cent of each new generation is harvested and turned into feed, while the lucky one per cent end up here.

It’s an unnerving place to visit: black soldier flies do not bite (they do not have mouths, the adults subsist on a small abdominal fat sack), but they are not shy about landing and crawling all over you. Most are contained by netting and stacked vertically — virtually no land is needed for breeding, which Jowett points out, is happening all around us. He points to a male and female connected rear-to-rear on the netting.

“We should be playing Marvin Gaye in here,” he laughs, adding the room must be kept hot and humid for optimal year-round production — one of the biggest production costs.

As thousands of flies around us buzz and copulate, I’m finding it strange how matter-of-fact are our hosts. As if designing a room optimized to maximize bug sex and then spending a lot of your life hanging out there is business as usual. Then I remember they are farmers. Maximizing healthy breeding is critical to raising livestock, and if Enterra’s gamble plays out, this will just be another livestock farm.

The eggs are taken to another area to hatch and grow progressively larger through several larval stages; all the bug feces and molted skins are collected and sold as fertilizer.

Black soldier flies are ideal for farming for several reasons: they mature faster than many other insects — including farmed bugs like mealworms (used for feed) and crickets (often raised for human consumption). They are also less picky about what they eat, which is one of the biggest environmental benefits.

We visit a food mixing warehouse, where “pre-consumer” food is collected from bakeries, food processors and warehouses. Most is discarded because of sub-optimal appearance or age. (Jowett estimates 30 to 40 per cent of all food produced for human consumption is wasted). On this day there are dozens of watermelons in the corner, hundreds of crates of ripe Roma tomatoes, and about a tonne of fresh pasta.

The food waste is mixed together and fed to the larvae in liquid smoothie form — Enterra even has a nutritionist on staff to ensure the optimal mixture for health and growth.

Enterra’s bugs are seasonal locavores, living a 100-mile diet particularly during the warmer months, when a steady flow of reject berries from local processors turns the feed a consistent shade of purple.

The larvae are not allowed to eat composted food collected from consumer households because regulators are adamant that the farmers know exactly what is going into the bugs. Enterra protein will ultimately produce food for human consumption, and feed our beloved pets, after all. To date, Enterra grubs have been approved as feed in Canada for poultry, pet (dog and cat) and salmonid feed, with approvals currently under review for their other products in Canada, the European Union and the United States.

After the bugs are cooked and dried (which kills the insects and any pathogens therein), they are pressed for oil and the remaining solids converted into a powdery meal. All products are then sold directly to feed companies. For example, Enterra sells grubs to a local North Vancouver pet food company called FirstMate Pet Foods, which produces a line of wet canned dog and cat food called Kasiks Fraser Valley Grub Formula.

The dog food, which was launched in March 2017, gets its protein from a combination of black soldier flies and wild coho salmon processing byproducts, with a tiny amount of vegetable protein.

"The response to a diet for dogs and cats containing insect protein has been overwhelmingly positive,” says FirstMate head of sales and marketing Matt Wilson. As consumers strive to find clean, healthy ingredients and give more consideration to their carbon footprint, they have also become increasingly open minded.

It’s this $29-billion-a-year pet food market that is a particularly promising area for growth according to Leung, in part because many pet owners are increasingly conscious of the impact feed from wild fish and factory-farmed animals has on the planet.

Jowett says millennials in particular, including many vegan pet owners, are “forcing manufacturers to look for alternative protein sources.”

Commercial aquaculture and particularly farmed salmon, the original market envisioned for Enterra bugs when the company began, remains a target market, albeit a distant one.

Jowett says supplying it will take more time. The Atlantic salmon fish farmer is demanding “‘where can I get my protein for the lowest cost of feed?’” says Jowett. So while his firm strives to match the current price charged for other feeds, it’s also keenly interested in a question that will set future prices: “Will society and the younger generations say, ‘I want fish that has been raised in a sustainable manner?’”

Shawn Hall, a spokesman for the BC Salmon Farmers Association, representing many of the province’s biggest net pen salmon farmers and feed companies, says there is interest in bug protein, but the reliability of bug meal supply will be a critical consideration influencing future adoption.

“Volume availability has been [a] challenge so far. Price certainly enters into it, but the trials that have been conducted [by B.C. salmon farmers] so far, and those done in hatcheries have been successful. So we’re really interested to see where this goes.”

Fish farmers could be forced to seek out protein from alternatives like bugs sooner rather than later. Faced with dwindling wild fish stocks and climate change, the availability of wild fish is an open question moving forward. According to a June report by the FAIR network of investors, warming waters in 2014 caused a reduction in anchovy yields in Peru, the world’s biggest exporter of fish feed. As a result, fish feed costs ballooned from $1,600 to $2,400 per ton.

Hall says that B.C. salmon farmers have reduced their wild fish meal and oil use to about 15 per cent (of each feed pellet) on average. This includes protein from B.C.’s Strait of Georgia herring roe fishery, where the eggs are the coveted product and most of the actual fish is reduced into fish meal and oil to be sold mostly as salmon feed.

“As aquaculture continues to grow, fish meal substitutes will be necessary, and this is where insects can play a key role,” says Cheryl Preyer, a spokesperson for the North American Coalition for Insect Agriculture, a trade group promoting the growth of the insects for food and the feed industry. “With amino acid profiles very similar to those of fish meal, insects can help by extending or replacing fish meal in those diets.”

Recent developments bode well for companies like Enterra offsetting wild fish used by aquaculture. In 2015, multinational agriculture company Cargill — the biggest private company in the United States — paid over $2 billion to buy Norway’s EWOS, which produces about one-third of the world’s feed for farmed salmon and trout. That same year, Reuters reported that Cargill launched trials testing bugs as chicken feed, but abandoned chickens to focus on using insects as fish feed instead.

“Sustainable protein is a key challenge, which is why Cargill is evaluating the viability of insects as part of the solution to nourish the world,” Cargill’s Benoit Anquetil told Reuters. The same article revealed McDonald’s is in the early stages of investigating the use of bug protein to offset their use of soy to produce chicken.

Preyer says commercial chicken production will be another key market for insects in feed and a natural one at that — left to their own devices, free-range chickens seek out bugs for food.

She added that the biggest players in the “insects as feed space,” are currently located in Canada (Enterra), the U.S., Europe and South Africa. Four of these grow black soldier flies, two are focused on mealworms, with one of these expanding into locusts and crickets.

Here’s a fun fact: forget bug larvae and any qualms you have about your pet or supermarket chicken eating them, because right now, you can walk into a Loblaws store, anywhere in Canada, and buy cricket flour approved for human consumption.

Which suggests we are already on the cusp of a redefinition of what constitutes animal feed and human food as well.

“The future is very bright for insects as feed,” says Preyer. “I’m hesitant to say that insect feed or food will replace anything outright, but with our global population expected to reach nearly 10 billion by 2050, we need to explore all options available to feed everyone." ![]()

Read more: Food, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: