On Thursday, Sept. 8, 1983, two men came together to meet at the Sandwich Tree restaurant on 1861 West Broadway St. in Vancouver. They were Larry Kuehn, president of the B.C. Teacher’s Federation and Fred Wilson, the Communist Party of Canada’s provincial labour secretary.

Unbeknownst to them, they were being closely watched by agents from the Security Service of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

These agents wrote in a memo that: “Wilson told Kuehn he was unable to tell the purpose of the meeting over the telephone,” but “it is felt that this meeting was brought about to formulate plans for the general strike.”

Once there, the two RCMP constables sat nearby and tried to eavesdrop, but (as they later wrote) Kuehn and Wilson “were too far away for any of their conversation to be overheard.”

Kuehn says today that he can’t recall what happened at the half-hour rendezvous. “All I got from that meeting was a good sandwich,” he chuckled during an interview with The Tyee. “I always had the same sandwich there.” He’s seen hundreds of archival pages about the RCMP counter intelligence branch’s spying on the BCTF from 1959 to 1984, and so he voiced no surprise or indignation. (Wilson could not be reached for comment.)

The potential “general strike” the Mounties referred to would have been the dreaded climax to the epic battle over the “Restraint Budget” of Social Credit premier Bill Bennett.

On July 7, 1983, the provincial government unexpectedly dropped a bombshell in the form of 26 bills that abolished rent controls, the Rentalsman and the Human Rights Branch, slashed social spending, gave public employers the right to fire employees "without cause," and called for reducing the provincial public service by 15 per cent. (The labour movement plans to mark the 35th anniversary this July 7.)

This shock wave of change was inspired by the neo-conservative Fraser Institute economic think tank and its chief Michael Walker, who nonetheless says today, “Nobody was more surprised than I to discover that almost all of the main issues I raised were addressed in the Restraint Program.”

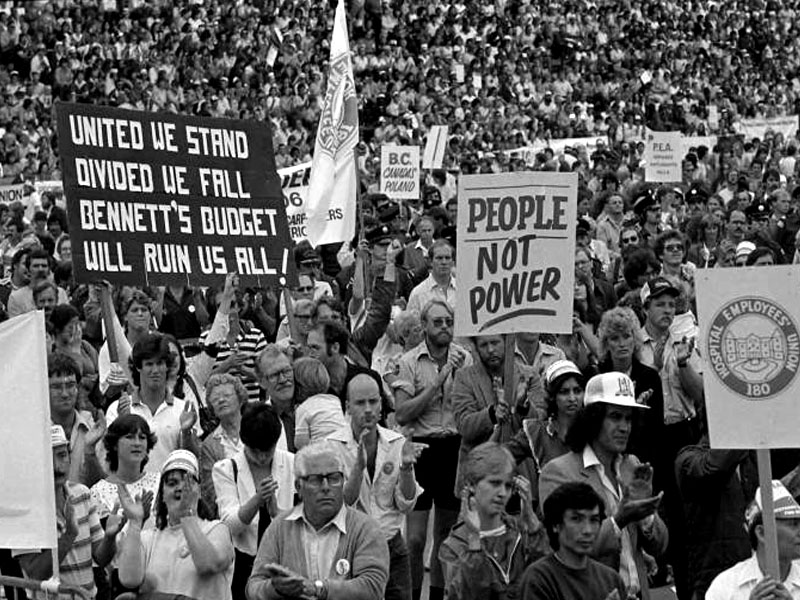

In response, it prompted the largest protest movement in B.C. history, one with no blueprint. The summer of 1983 was consumed by a feverish power struggle with the highest conceivable stakes, with odd alliances joined in a tangled web and factions that seemed (to the delight of the Socreds) to spend almost as much time fighting each other as Bill Bennett. “Some union leaders hated each other’s guts, and would have shot their union brothers if they could,” said former B.C. Federation of Labour president Art Kube, who sat down in his Surrey home to talk for an hour to The Tyee.

The B.C. Solidarity Coalition citizens’ protest movement was soon formed, separate from the unions’ more moderate Operation Solidarity. (Kube was the key link by being on the board of both groups.) It was a diverse, broad-based gathering of dozens of community groups, some of whom hitherto had long shunned each other, now banding together for their mutual survival.

Yet worried RCMP agents wrote in memos that “subversives” from the Communist Party of Canada created and controlled the coalition. The Mounties believed the party exploited public fears and exacerbated labour unrest like puppeteers, all with the goal of taking over the provincial government and toppling the B.C. capitalist economic system.

More than 300 pages of fascinating RCMP records were obtained by The Tyee under the Access to Information Act. These are at times contradictory and raise several questions. How influential — if at all — were Communists in the Solidarity movement? Did the movers and shakers within the coalition indeed have a different and darker real agenda from their public one?

‘Pretty ridiculous’

When The Tyee told union leaders of the memos, most burst out laughing. Cliff Andstein, then chief negotiator for the BC Government Employees Union (BCGEU), called the Mounties’ claims “paranoid and stupid.” UBC labour relations professor Mark Thompson said, “That’s the biggest load of nonsense I’ve heard in decades. I don’t know what they were smoking, but it says more about the RCMP than about Solidarity.” “The memos sound pretty ridiculous,” said journalist Allen Garr, author of Tough Guy, a 1985 book on the Bennett budget. “Those claims are all new to me.”

“I don't know whether or not to laugh or cry,” former Communist and famous folk singer George Hewison told The Tyee by email. “What is incredible based on the memos is that they actually believed their own propaganda. It should be abundantly clear they have learned nothing in a century, i.e., communism is not a foreign import. It grows out of the injustice of a very chaotic economic system, and no amount of state spying/subversion can change that reality.” (Hewison would not reply to specific questions on his role in Solidarity.)

The RCMP interest was first aroused when Hewison, secretary of the Communist Party-influenced Fisherman’s Union, organized a meeting that July 11 in the Fishermen’s Hall. Nearly a hundred people including teachers, union members, feminists, church members, seniors and tenants crowded into the room, and then promptly formed the Lower Mainland Budget Coalition (a forerunner of the Solidarity Coalition).

“It becomes fairly obvious... that the Coalition is completely controlled by persons considered subversives,” the RCMP wrote. Former B.C. labour journalist and author Rod Mickleburgh has a different version of events: “The first meeting after the budget was called by Hewison indeed, but then he turned it all over to Art Kube, who had fought against Communists his whole life.”

The RCMP added on Dec. 6 that the Communist Party wanted to make the Solidarity Coalition into an “extra parliamentary opposition” to ultimately lead the workers “in the overthrow of the capitalist system.” Then in January 1984: “The Communist Party of Canada appears to have been the main impetus behind the launching of both the LMBC and the Solidarity Coalition. The organizational strengths and cohesiveness of such groups as the CP of C would easily allow it to dominate such a structure.”

Yet later in the memo the RCMP qualified that statement. “There is no intent on our part to imply that the entire Solidarity Coalition is subversive; nor that the [CP] has been the sole instigator of the labour unrest in British Columbia. We do however believe that the CP of C and other target groups are actively trying to exacerbate the unrest that exists, and use their current efforts to build political momentum for future advantage.”

What exactly was a subversive? “‘Subversion’ was always a very slippery concept, never clearly defined in law,” said Reg Whitaker, a University of Victoria security expert. “It necessarily assumed intent rather than actual action. But intent is in the mind and of course raises questions of freedom of thought and expression. In practice, the RCMP tended to define Communism as subversive, so they didn’t give much thought to the implications.”

Critics say there are many reasons the RCMP needn’t have worried about Communist influence at all. Firstly, “they had no real world power,” said Mickleburgh. “How could they when they only got 200 votes or so in elections? Most were political nobodies.” Secondly, Whitaker said that some Communist Party leaders successfully improved workers conditions and benefits, a result that was more likely to lower the revolutionary urges of workers than to heighten them. Thirdly, the Mounties couldn’t or wouldn’t see that the Communist-union political influence was more likely to work in reverse. “The Communists were no real power in Solidarity, really the opposite,” said Kube, chuckling merrily. “In these situations I would use them.”

“Everyone knew who the Communists were, they put the views out there openly, so there was nothing subversive about them,” said Mickleburgh.

On the RCMP claims, Whitaker said, “That’s classic security service Cold War boilerplate on the revolutionary nature of the CP. The curious thing is that they never did find a smoking gun: not a shred of evidence of actual revolutionary activity. CPers who did enter trade unions never had the opportunity to turn revolutionary rhetoric into practice: they were too busy just being good unionists securing better wages for their members. Even a few unions that ended up being run by CP officials were not really distinguishable from those closer to the CCF/NDP.”

“Those were certainly difficult times and agitators of all sorts like to fix on other’s disaffection to push their own brand,” said the Fraser Institute’s Michael Walker, whose father was a union leader. “So you know, commie, schnommie — what matters is the ideas people run with, not with what they call themselves.”

Nonetheless, union leaders abhorred extremists in their higher ranks, and at times cleaned house. The RCMP wrote in November 1983 that the BCGEU was “void of subversives at the senior decision making level, following a carefully planned, in-house purge by General Secretary John Fryer.” They added that the BCGEU had been trying to purge itself of aggressive radicals since 1980, and B.C. Communists had tried to start a general strike as early as 1981.

In another memo, an informant reported on a meeting of the Solidarity Coalition on Sept. 15, 1984: “Kuehn and [Jean] Swanson dealt a crushing blow to the influence of [Communist] Party members in running the Coalition.” With Kuehn in the chair, “the whole meeting was carefully controlled by him and he used some sneaky maneuvers throughout… It is interesting to note the Party’s reaction to a taste of their own medicine. However, source feels that Kuehn will continue to use the Party and its members when he feels it is to his advantage.” (Kuehn said he can’t recall the meeting.)

On the members within the Solidarity Coalition, the RCMP wrote, “Most of these groups are union sponsored and controlled, and do not represent radical interests such as homosexuals or racial groups,” and yet later, by contrast, the coalition might “create a forum for all the politicos and crazies that are presently without structure.”

In its coverage of the Empire Stadium rally of Aug. 10, 1983, the Vancouver Sun was chastised for unfairness after running a front page photo that may have suggested that the parade was led by a small delegation walking some distance from the front of it: the Communist Party of Canada. Yet if that impression was created, the RCMP would have fully agreed with it.

Melting into the shadows

There is a second level of historical interest here, for the memos represent the last hurrah, or gasp, of the old hardline RCMP Security Service. In July 1984, the Mounties intelligence branch was replaced by the more educated and cosmopolitan Civilian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), and this transition overlaps with the B.C. Solidarity movement. But the early 1980s was the totalitarian pre-Gorbachev era in Russia, and the RCMP’s political outlook appeared largely unchanged from the 1950s Cold War period. “It was a different world then,” said Walker of 1983. Still, RCMP memos never mentioned foreign influence in the B.C. protest movement, and some contradict each other on their estimates of Communist influence.

The Tyee searched but was unable to locate any RCMP agents of the time either willing to speak or who were still alive.

There is a popular image of the Mounties — the “Horsemen” — as old-school cops labouring diligently on political analysis, with their trenchcoats, cigarettes, handlebar moustaches and bushy sideburns, peering through bulky binoculars on late night stakeouts in their big sedans. (Their scandals and lawbreaking are chronicled in John Sawatsky’s 1980 book Men in the Shadows.)

It is also important to recall the context the memos were written in, which might partially have elevated their writers’ fears of “revolution.” In the stormy summer of 1983, many B.C. Mounties — separate from the intelligence branch — had their hands full on other fronts. The legislature was turned into an armed camp. The RCMP set up a security headquarters in the basement and added bodyguards for Bill Bennett upon verifying death threats made against the premier and his wife, Audrey. Such death threats and heavy vandalism also plagued the Fraser Institute’s Walker and union leaders such as Cliff Andstein.

As Garr relates in Tough Guy, the legislative clerical staff was run through the RCMP’s lectures on terrorist attacks, and shown a slide presentation depicting the remains of bombed buildings and bodies dismembered by explosions, letter bombs and telephone bombs. On Sept. 21, a false bomb scare drew the army’s bomb squad to the legislative mailroom. The Mounties also worried in memos about a general strike’s impact on crime and public order, and Attorney General Brian Smith said it was not impossible that if unionized B.C. prison guards walked out, RCMP personnel might have to fill their places.

“There were lots of local agitators including many academics from UBC who joined in villainizing those like myself who supported the objectives of restraint and did so in such a way as to inject a kind of class struggle/war meme into the discussion,” said Walker. “Some of them were so inflammatory in their allegations about me and the Institute that they crossed the line from scholarly criticism to rabble rousing and a deliberate attempt to inflame the passions of people with alarmist rhetoric, which undoubtedly encouraged those who the RCMP were worried about posing a threat to my family’s security. I have never forgiven those left of centre people at UBC.” He recalled how he had been burned in effigy in 1983, and how a bomb had destroyed a Fraser Institute elevator in 1978.

In regards to RCMP surveillance methods, Whitaker said these probably included informants, plants, phone tapping and mail opening. Some unionists said the information in the memos could only have come from highly placed insiders, although one can only speculate on their motives and if they were paid or not. “It was pretty clear someone was sitting in our BCTF meetings and reporting out,” said Kuehn. (At one point in 1983, the RCMP wrote the existing “Level 3” surveillance was not enough, and so a more intrusive “monitoring Level 2 is now required,” though it is not clear what these terms mean.)

“The RCMP had developed a pretty extensive network of sources, which could include everybody from social democratic Cold Warriors thinking they were doing their patriotic duty to union bureaucrats just trying to fend off Communist or left-wing challengers,” said Whitaker. He doubts there was any extensive use of money as the main inducement for informants.

A union leader, who asked not to be named, strongly suspected that one obscure activist, who popped up at meetings to urge radical action and then abruptly vanished after the Kelowna Accord, might have been an RCMP agent provocateur, of the sort infamously used in Quebec in the early 1970s. Whitaker said that a scenario of a mole is quite possible, but it is hard to determine if such a provocateur would have been controlled by the RCMP or acting on his or her own. Such people were not always easy to manage, and would sometimes file exaggerated reports of radicalism.

Did the RCMP oppose the 1983 B.C. union and citizen political goals in general, or only the possible Communist Party influence — and did they do so for legitimate public security reasons or political philosophy?

“That’s a difficult question,” said Whitaker. “They can say they were only interested in the bad apples, but if in order to find the bad apples they have to intrusively surveil the entire barrel, and it’s hard to tell the difference between targeting bad apples and targeting all apples. I see precisely the same dilemma today with regard to the anti-TransMountain protest groups.”

No revolution

The grand Solidarity campaign ended anticlimactically. Two weeks after a protest rally of 70,000 people in downtown Vancouver on Oct. 15 (one that some union moderates wanted to cancel, fearing a riot), 40,000 members of the BCGEU legally walked off the job, followed by thousands of teachers illegally striking, with more sectors soon ready to join them for a total of 200,000. The BCGEU negotiators won a deal on wage increases, and the death of Bill 2 and Bill 3 concerning employment rights — achievements underrated today.

Oct. 31 was, as Mickleburgh put it, “the night that B.C. held its breath.” (His account of the events can be found here, and here.) Fearful of a looming general strike, one resulting in dire consequences, BC Fed vice president Jack Munro settled with Bennett on Nov. 13 in a truce dubbed the Kelowna Accord, which left the other bills slashing social services intact. The move pacified the BCGEU but left the citizen groups in the Solidarity Coalition feeling betrayed and bitter to this day. (“It was a total mistake in my view,” said Kuehn. “Jack gave up too much.”) As the RCMP noted, while the BCGEU and other unions opposed the whole Restraint package, “they did not appear ready to include its abandonment as a prerequisite to end the strike,” whereas the coalition insisted upon it.

Summing up the RCMP complaints of Communist-union influence, Kube’s reply, after a pause for reflection, may surprise a few: “Listen. Sometimes I wish we had more of them now, to push the leadership of the trade union movement to the forefront. Because we’ve grown too soft.”

ADDENUM: Under their eye

A selection of quotes from RCMP memos on the Solidarity Coalition. (See the link above for pdfs of some of the actual documents.)

June 28, 1983 - “The depth of subversive involvement in the Solidarity Coalition is extensive, with Party people holding major positions within the group.”

Nov. 2, 1983 - “The involvement of subversives in this labour conflict is insignificant and negligible in that they are not in a position to influence negotiations.”

Nov. 14, 1983 - “If public peace is not now a concern to law enforcement agencies, and the public welfare a concern to government, it is my opinion that both agencies will be forced into intermediary action on a large scale.”

Nov. 15, 1983 - One RCMP assessment suggested “minimal role” played by Communist Party (CP) in Solidarity Coalition. But the B.C. branch said, “Some questions remaining about the role of certain radical elements,” pointing to leftists within the Social Workers local who had tried to overthrow the current BCGEU executive years before.

The BCGEU was moving into facilities of the Union of Unemployed Workers, which has significant input from CP of Canada, the RCMP wrote.

“HQ request to have ‘surveillance’ placed on [CP official Fred] Wilson to ascertain through whom the Party will attempt to influence the stand of the unions and/or Solidarity Coalition, with respect to demands upon the Socred government.”

The RCMP also worried about “subversive influence” in the B.C. Teachers Federation.

April 2, 1984 - Because of unrest in forestry and construction industries, Solidarity might soon be needed again. Yet one source “expressed the feeling that many senior trade unionists are hesitant to reactivate the Solidarity machine unless absolutely necessary, as it had come dangerously close to getting out of control during the BCGEU and Teachers’ strikes of 1983, and had in fact brought some discredit to the labour movement because of the many less than reasonable demands it made of the provincial government.”

In one opinion, Operation Solidarity is labour-run and controlled, staffed by moderate unionists and not a threat at this time. The more radical unionists have joined Solidarity Coalition, and this may cause friction in future.

“The labour movement, both at the provincial and national levels, were said to have been reluctant, initially, to actively organize unemployed workers, because of the possibility of the radical left using them to their own political ends.”

“While membership is quite broad, COPE [The Committee of Progressive Electors, a Vancouver civic party] is considered a Communist Party front.”

May 21, 1984 - “The labour movement is gravely fragmented and the labour leaders are fighting among themselves.”

July 31, 1984 memo - “It was indicated that the BC Federation of Labour was afraid the CP of C was trying to take over Operation Solidarity, however Wilson advised that this was not their intention.”

“Wilson mentioned that the CP of C wanted a one day general strike, however Operation Solidarity would not sanction that.” The Solidarity Coalition seemed to go “stagnant” after the Empire Stadium rally of June 10, 1983.

CSIS memo, Sept. 24, 1984 - “It appears the [Communist] Party is struggling to keep the Coalition alive, but it seems to be an uphill battle.” ![]()

Read more: Labour + Industry, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: