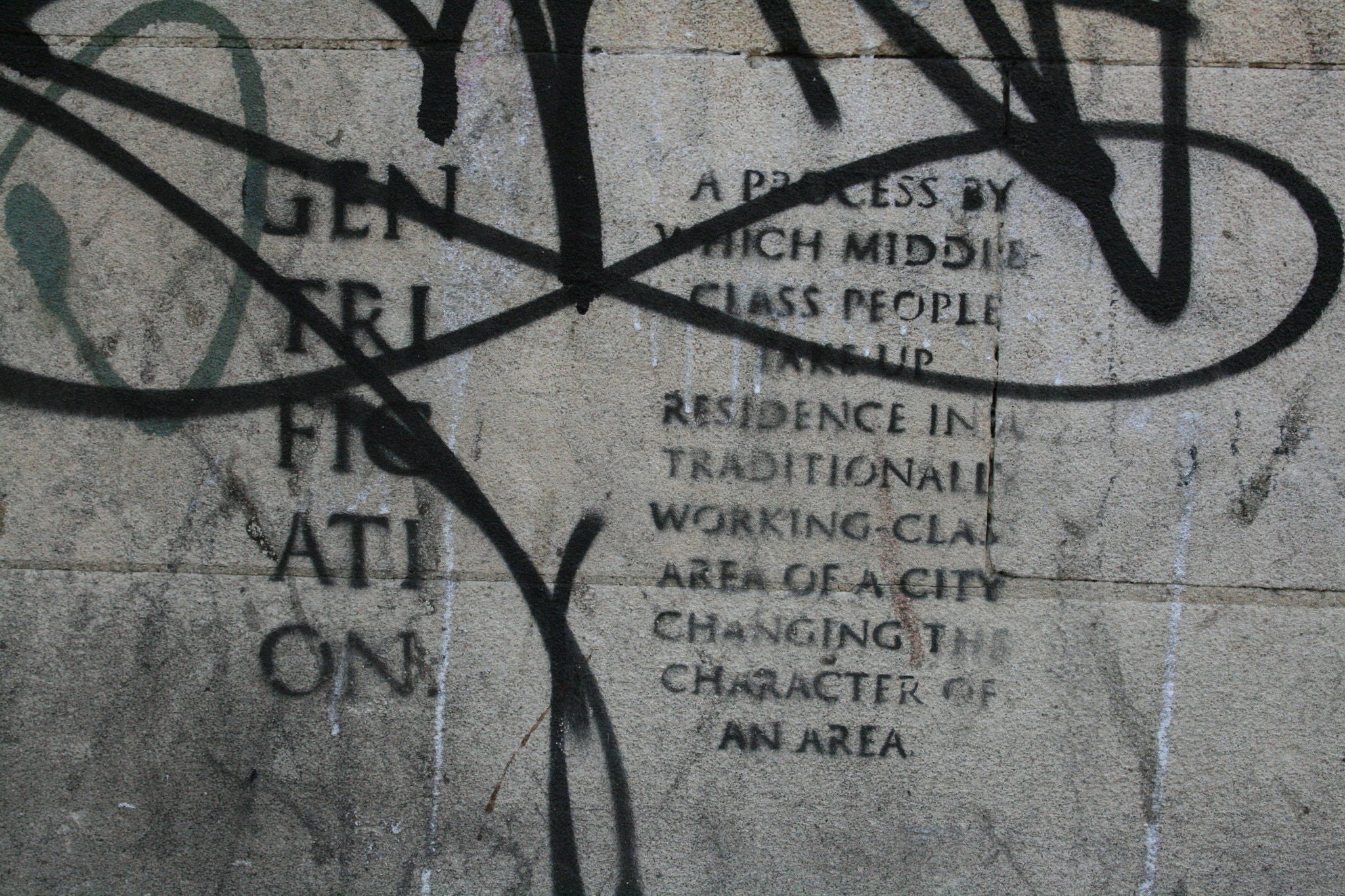

When a beloved Brooklyn deli was being pushed out of the neighbourhood due to a 250 per cent rent hike, locals took action. They created posters selling mock high-end products — baked vegan cat food, wind-powered kettle crisps, grass-fed Himalayan tuna salad — and plastered them onto the deli’s windows. It was an artsy jab against gentrification.

New York City has been dealing with such gentrification since the 1990s. In a vicious cycle, wealthier newcomers pushed real estate prices up, drove longtime residents from affordable homes, and attracted upscale restaurants and boutiques that did the same to mom-and-pop businesses like the deli, which finally closed last year.

With residents in some Canadian cities now facing similar challenges of displacement, a growing number of provinces are looking south for some solutions. Specifically, they’re looking to a legal tool that New York is also wielding in its fight to keep the Big Apple affordable for its 8.4 million people.

That tool is called inclusionary zoning. Invented in Virginia in 1971, it got a boost from a precedent-setting court decision in the mid-‘80s in New Jersey, and in 2014, newly elected New York Mayor Bill de Blasio made it a centrepiece of a $41-million USD affordable housing plan.

“If you leave the market to its own devices,” de Blasio told Bloomberg last year, “those big, shiny glass buildings will go up and you’ll see a lot of people displaced. The role of government is to create some balance, to protect the broader public interest. And until we had some muscular laws, that wasn’t going to happen.”

Here’s how “muscular” inclusionary zoning works. Developers who want to build a project on land with that zoning must ensure that a certain percentage of its units (usually between 10 and 20 per cent) are “affordable.” Typically, that’s defined as renting or selling at less than the market rate and available only to those with incomes below some determined level. On purchased units, those conditions are imposed on subsequent owners through restrictive covenants, which keep the affordable housing requirement in place. They can last anywhere between 30 years and the full life of the unit.

It sounds simple. Communities get affordable homes at no extra cost to taxpayers. Lower-income households can be housed near amenities they depend on, like transit and job opportunities. And residents will come from a mix of social backgrounds.

But mandating that affordable housing be included with market-price dwellings can meet resistance. Better-off residents might not want lower-income neighbours. Developers might refuse to build in those zones, worried about their profits if they have to sell or rent some units for less than the market will bear. And then there’s the question of fairness — if one family has worked and saved enough money to locate in a prized area, why should other people be allowed to move there for cheap?

But there are counters to those arguments, said University of Toronto’s David Hulchanski, an expert on housing and urban inequality. “If you let the market mechanism run wild, only people with lots of money will be able to afford popular and dynamic cities.”

That’s become a very real fear in increasingly expensive Canadian cities like Vancouver and Toronto. In response, Canadian provinces are slowly conceding inclusionary zoning powers to their municipalities. (Ontario has; British Columbia hasn’t.)

As they do however, experts say it’s important to get the details right. Done well, inclusionary zoning doesn’t just boost affordable housing. It can also mean cities with a greater mix of incomes, and the dispersion of wealth and poverty beyond concentrated neighbourhoods of each. But there can be doubts about how far to push a good deal, as well as the subtle ways that some supposedly inclusionary projects effectively ostracize lower-income tenants.

In or out in the Garden State

Inclusionary zoning made its breakthrough in New Jersey, where a landmark court ruling declared that affordable housing was the responsibility of municipalities. The case arose when a local government attempted to displace effectively all the black residents living in one town.

Mount Laurel, New Jersey, was steeped in black history. Many black people had lived in the farming town since the Revolutionary War, and it became a stop on the Underground Railroad.

In the 1960s, the local government wanted to develop the town. That meant attracting high-end homes, commercial centres, and industry. Affordable housing got no thought. Most members of the black community had modest incomes and would be unable to afford to live in their own homes once development raised real estate prices. That made “development” look like an attempt to force black residents out of town.

In response, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) sued Mount Laurel Township. After a decade of legal battles, the New Jersey Supreme Court handed down one of America’s most important civil rights decisions in 1983. It ruled that it was a mandate on every municipality in the state to provide a “fair share” of affordable housing.

The controversial decision — codified two years later into state law — proved to be a challenge to implement. Some municipalities complied. Some didn’t. Those that didn’t faced additional lawsuits.

Nonetheless, by 2014 over 65,000 affordable housing units had been built in New Jersey in the wake of the Mount Laurel ruling, a significant number for America’s most densely populated state, as well as one of its most expensive.

And inclusionary zoning has been the tool of choice to make it happen. New Jersey, along with California and Massachusetts, is now home to 75 per cent of U.S. inclusionary zoning areas.

The zoning mandate hasn’t eliminated NIMBYism. And that has tinged how some “inclusionary” projects are designed.

Some buildings with both market and non-market housing are equipped with so-called “poor doors” — separate entrances for the residents of the reduced-cost units. (Several buildings in Vancouver that include both types of units as a result of special deals with developers, do this. New York banned the practice in 2015.)

Other projects clump below-market units into one area rather than disperse them among other residents, a bit like an “affordable” ghetto.

Advocates say the apprehension about mixing income classes is undue. “You can see a lot of fear at first,” said Anthony Campisi, a spokesman for Fair Share Housing, a non-profit dedicated to ensuring compliance with Mount Laurel.

“But once affordable units are actually built, there’s a ton of evidence that shows there’s no negative side effects. Opposition disappears as these projects integrate with the larger community, and we’re seeing a growing consensus among many municipalities that they should, and can, [use mandatory inclusionary zoning to] meet their housing obligations.”

Canada plays catch-up

As Canada confronts housing crises of our own, a growing number of cities and provinces are experimenting with inclusionary housing policies. But mandatory zoning for affordable housing quotas remains mostly untried.

Some municipalities offer developers extra density in exchange for community amenities such as affordable housing. However, developers may choose to offer something else, like a park, instead.

Vancouver, Toronto and Montreal all require developers applying to rezone a large parcel of land to residential use to set aside a percentage for affordable housing. The idea is that the profit made from rezoning will compensate developers for the cost of including affordable housing. But the percentage isn’t defined or mandatory. Instead, city staff must bargain with developers over what each new project will include.

One thing holding Canadian cities back from adopting more “muscular” inclusionary zoning is our different constitutional setup. Canadian municipalities simply don’t have the same autonomy that U.S. cities do. They’re tightly constrained by what their provincial governments will allow.

According to Richard Drdla, a Toronto-based affordable housing consultant who has studied inclusionary zoning for 20 years, “the main obstacle has been that [Canadian] municipalities have lacked the authority to require developers to provide affordable housing as a condition of a development approval. In contrast, municipalities in many U.S. states can do whatever they want unless they are told not to do it by their state governments.”

Attitudes about who is responsible for affordable housing are also different. Whereas many U.S. “municipalities have clearly taken a much stronger initiative in using their own powers to provide for affordable housing without any state or federal involvement,” said Drdla, Canadian municipalities generally think of affordable housing as solely a provincial and federal responsibility. “It’s almost black and white in terms of how different our attitudes are.”

That’s apparent in Manitoba. The province was the first in Canada to give its municipalities the power to enact inclusionary zoning three years ago. But so far none has taken up the offer. Drdla says that it’s an indicator of municipal indifference to affordable housing.

The regional municipality of Halifax, by contrast, doesn’t have the power and wants it.

“The inclusionary aspect of where you can live is very important,” said Halifax regional councillor Steve Craig, “and it’s something that municipalities can influence through bylaws and land use.” There are 200 communities and neighbourhoods in Halifax, and Craig said he doesn’t want to see people limited in choice just because of their income.

But change is coming.

Toronto has been asking for inclusionary zoning powers for over a decade. Ontario granted it in principle just last month. And Alberta also approved draft legislation for inclusionary zoning last year.

Lessons from the US

For municipalities in the provinces that allow inclusionary zoning policies, there are lessons they can take from the U.S.

One is not to get too greedy in mandating affordable housing. San Francisco’s city controller, Ben Rosenfield, warned his mayor and council last year that the city could drive down development if its citizens approved a ballot proposal to hike the affordable housing quota to 25 per cent of new units. San Franciscans approved the measure anyway, in a vote last June. Reports began to surface that the number of development applications in those areas had “plummeted.”

Somewhat easing developer anxiety is that land in inclusionary zones usually sells for less than other properties, reflecting the fact that fewer market units may be built there. Municipalities can also waive other fees for projects in these zones.

Meanwhile, clarifying the requirements about including affordable housing, making them mandatory, and applying them equally to all developers, creates a level playing field for any who choose to build in inclusionary zones.

Inclusionary zoning probably won’t solve Canadian cities’ housing crises alone. But the evidence from the United States is that, done right, it can help ensure that people of all incomes continue to have a place in them. ![]()

Read more: Housing, Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: