Penny Gurstein remembers the bustling energy that electrified a dramatically refurbished Air Force hangar on Vancouver's Jericho Beach 40 years ago this month.

For 12 days starting in late May 1976, world leaders, top urban thinkers and activists descended on Vancouver for what then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau described as "one of the most important meetings ever held by the United Nations."

At the time a 25-year-old architecture student at the University of British Columbia, Gurstein volunteered to report on the UN's inaugural conference on human settlements -- dubbed Habitat I -- for the official daily bulletin.

Today, with a third Habitat conference approaching in Ecuador this October, few recall an event that experts say marked an historic turning point in housing and city planning. Instead, the city that hosted that original meeting has drifted far from the principles it identified for more successful urban living.

Back then, the so-called Vancouver Declaration on Human Settlements -- perhaps presciently -- called for curbs on commercial real estate speculation and foreign investment in land.

"The use and tenure of land should be subject to public control because of its limited supply," the Declaration read. "The increase in the value of land as a result of public decision and investment should be recaptured for the benefit of society as a whole."

Those issues continue to haunt the city of Vancouver and the Lower B.C. mainland four decades on. A sense of frustration with existing housing policy has replaced what Gurstein and others recall as a mood of optimism and possibility.

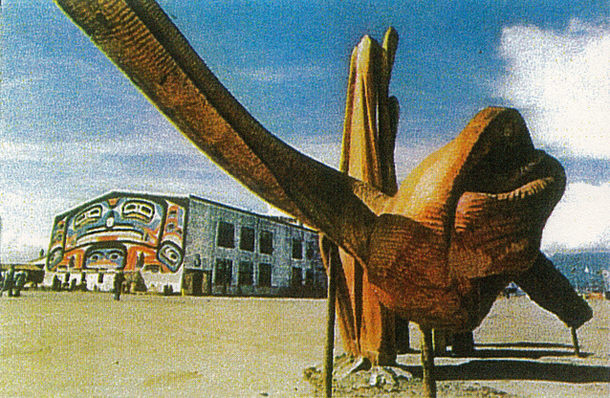

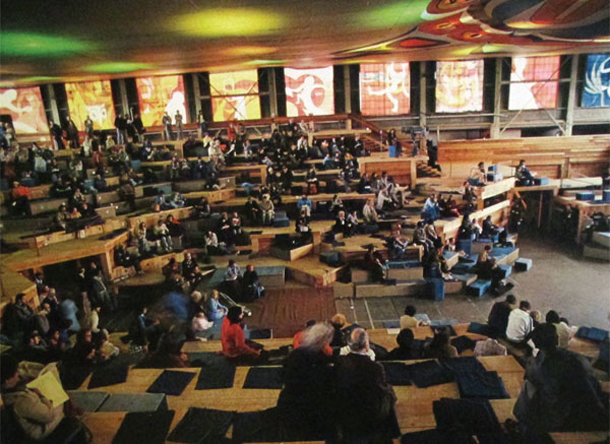

Then, as politicians bickered over geopolitical conflicts in the main conference venue at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre downtown, nongovernment organizations, housing advocates, and ordinary citizens filled an echoing hangar converted for the occasion into a display space of massive stacked wooden blocks where the likes of architect Buckminster Fuller, anthropologist Margaret Mead, and Mother Teresa could be spotted exchanging ideas with the masses.

"There was an amazing air to the place," Gurstein recalled. "The people there for the Habitat Forum were some of the most critical thinkers in the world.

"I learned about how important it was that people are able to participate in defining and even building their housing. These were all new ideas; now they've become mainstream."

The conference also set Gurstein on a new personal course toward urban planning, where she felt she "could be more influential on a larger arena." Today, she’s director of the UBC School of Community and Regional Planning.

Fewer rules, more optimism

Another participant was half Gurstein's age at the time. Lindsay Brown was 12 when she walked onto the Jericho grounds in spring 1976. Men with chainsaws were cutting up logs hauled from the beach to transform the site's five buildings into a bizarre and forward-looking alternative congress venue.

As an example of how unregulated life was then, she and a friend walked onto the site one day and were promptly put to work.

"They issued us hardhats and we started sweeping up sawdust," she recalled. "Everybody wanted to be involved. It was an era of incredible idealism -- that we were part of a global, no-borders society, that we were going to help end poverty for children."

Brown later befriended the man whose idea it was to reclaim the Jericho hangars, the late broadcaster Al Clapp, who died in 2013. She asked him why he allowed so many local children onto a dangerous industrial work site, full of "guys in big steel toed boots" and heavy machinery.

"I didn't see any reason to keep them out," she recalls he replied.

Brown, who has become something of an expert on the utopian 1976 gathering, credits Clapp with "cleverly" manoeuvering officials to let him redesign the Jericho site to demonstrate how ageing buildings and disused land could still be "saved for public use." The idea was echoed in the final Vancouver Declaration.

Yet outside planning circles, and the dwindling number of original participants, few remember what at the time was a world news-making event.

"It's an odd paradox," Brown said. "For those who participated who are still alive, the memory is completely vivid. Beyond that, there is almost zero public consciousness.

"It's shocking how buried it is. Even the UN doesn't seem to know the history of Habitat I!"

Brown hopes to change that with an upcoming book, Habitat '76, to be published this fall and launched at Habitat III in Quito, Ecuador. (The book can also be pre-ordered on Amazon).

‘Amnesia’ about needed lessons

Monty Wood is one for whom the long-ago event remains fresh. A recent graduate at the time, he attended both the official UN congress and the non-governmental forum at Jericho, the now semi-retired architect jokes, "with a degree of naive enthusiasm."

It was an experience he now calls "profound," memorable for the enthusiasm of the attendees, but even more powerfully for their common idea of "maintaining a non-commercial approach to housing."

The Declaration that flowed from the official event became "a sort of manifesto," he said. "Most of it was benevolently wise. One [idea] in particular was how to take the speculation out of domestic real estate."

Wood dismisses the suggestion that the conference failed since neither Canada nor most of the other countries that sent representatives ever followed many of its recommendations, nor did delegates reach full consensus before adopting the declaration.

"I don't think it was a failure at all," he said. "We needed those discussions."

And, he adds, as Vancouver struggles with skyrocketing real estate values, disruptive property speculation, and shadowy offshore investment, it needs to remember those discussions today.

Brown agrees. "Why is there such amnesia about Habitat?" she's asked many of its former participants. Some blame generational change, with declining interest in the issues. Others speculate that it was "too wonky" for citizens today.

"But some," she said, "believe there is a reason the principles of the Declaration were suppressed.

"It was very radical. The geniuses behind it knew that unless you were talking about national control of the economy, you weren't going to get anywhere. Without addressing inequality, you'd never get anywhere building liveable settlements."

But the election three years later of Margaret Thatcher in Britain, and in 1980 of U.S. president Ronald Reagan, brought an abrupt end to such communitarian thinking. In the years that followed, they drove the world’s adoption of "free" market policies and public service cuts, justified by hard-line neoliberal ideology.

The decade's idealism proved "no match for neoliberalism and globalization," Brown observes. And as a result, she argues, "the failures of Habitat were not really its own. You had very good principles that made a tonne of sense, up against a tidal wave of history going in the other direction."

That toll of that history is now apparent in Vancouver, she says: "We have the second-worst affordability in world, which is pretty ironic considering we hosted the conference."

Idealism flagged

Her analysis is shared by one of today's most influential urban thinkers. An emeritus professor of planning at the University of California, Los Angeles, and honorary professor at UBC, John Friedmann was seven years into his research after two decades as an overseas development planner when the Vancouver Declaration was adopted.

"At the time, no one knew that 1976 would be what, in world historical terms, I would call a 'hinge' year," Friedmann told a UBC Urban Design Forum in March, one “that marks the end of one era and the beginning of another that in 1976 none of us clearly envisioned."

In the new era, he said, "neoliberal gurus encouraged fierce inter-city competition to attract footloose capital. There would be winners and losers."

So, what should we learn from Habitat's failure to stand up to the neoliberal assault on the very idea of a public interest in affordable, appropriate housing?

Not to abandon that distant era’s impulses to social justice, Friedmann says, but rather to build new solutions from the ground up, directly engaging those citizens who will be most personally affected by urban planning decisions.

"Long-term, visionary planning," he said, "makes little sense, since many of these plans are likely to come to grief."

Gurstein chuckles at Friedmann's grim assessment of idealistic urban design. "I'm not as pessimistic!" she said.

The problem, she believes, isn't idealism. Instead, it's our government's failures to uphold the Vancouver Declaration's vision of housing freed from the influence of real estate speculation and developments disproportionately aimed at the wealthy.

"All the other forces will do what they're going to do," the city resident and UBC authority argues. "We need government intervention in the urban realm again."

A moment to think of neighbours

Today a small historic plaque at Jericho Beach recalls a singular "moment in time … when people came together to think of their neighbour."

The city tore down the Jericho Beach wharf that once welcomed the world outside the long-gone aircraft hangars in 2011. One of the last Habitat demonstration projects, Marine Gardens, is slated to be replaced by new housing towers.

Another, in False Creek South, frets about its future when city land leases expire over the coming decades.

Forty years after the last gavel fell at the UN’s inaugural Habitat conference, Gurstein serves as a director of the Centre for Human Settlements at UBC, which seeks to preserve its documents and knowledge.

But she believes Habitat's real influence can't be read in buildings or archives, but in what the city has since become. "It really did help shape what happened to Vancouver after," she said, "because there was a critical mass of people who started to really understand our city."

Nonetheless, she adds, "we've gone down a different path" since then. Had the city followed the Declaration that bears its name, Gurstein believes, "we'd probably have much better cities than we do now." ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Federal Politics, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: