[Editor's note: This article was corrected to reflect the fact that since being interviewed but before this story was published, Leslie Carson no longer works at St. Joseph's.]

Guelph, Ont. -- "Hospital food" is one of those phrases that evokes an almost visceral reaction from anyone who has had the displeasure of experiencing it first-hand.

Bad hospital food stories are nothing new, but in the past few years there has been a renewed call to improve the healthcare system's approach. Not just for the sake of patients' palates and morale, but for the local food system and environment.

We expected that hospital administrators must know about their bad food problem. But we wondered: Are they doing anything to fix it? And if so, what?

The good news: it's happening. There are local food champions within hospitals and the wider healthcare system. The bad news? They're up against a system that has put food on the chopping block for the past two decades.

When Leslie Carson was hired as food services director for St. Joseph's Hospital in Guelph, Ontario, in 2006, her boss had one question for her: Can you make my really bad food complaint headache go away?

"And basically, if you can, you can do no wrong," Carson said laughing, when I spoke with her earlier this year. "So I had a lot of freedom to correct things."

In the six years since then, Carson helped transform the food service at St. Joseph's by going back to the basics she learned studying nutrition and food science at the University of Alberta. In other words, going back to cooking from scratch, 'home'-made meals from fresh, whole ingredients.

Her approach turned heads and caught attention. Carson was recognized as a local food champion by the Ontario Greenbelt Foundation last year, and received an award for leadership from the Ontario Hospital Association and the Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care.

And then, in September of this year, she and St. Joseph's parted ways.

Carson told the Guelph Mercury that she was fired, but was not given a reason by her employers. Barbara MacRae, the hospital's director of communications confirmed that Carson is no longer with St. Joseph's but would not comment further, citing confidentiality. When asked if food service has changed since Carson left, MacRae said "not to my knowledge."

Carson could not be contacted for comment.

A kitchen never meant to cook

When Carson graduated from U of A in 1987, most Canadian hospitals still had well-equipped, well-staffed kitchens, where cooks produced almost everything from scratch.

That changed in the 1990s. Budget cuts and pressure to privatize saw many Canadian hospitals outsource food service to companies like Aramark, Sysco, Compass and Sodexo. Cooking staff were laid off, and kitchens renovated to accommodate larger freezers and "rethermalization" ovens that could quickly heat up pre-packaged meals from centralized plants. The shift from conventional cooking to heat-and-serve meals reduced labour costs by as much as 20 per cent.

A decade later, however, the "good food" movement has turned its focus from individual consumers to big public institutions like hospitals -- with some successes.

Kaiser Permanente, a private, non-profit health care provider in the U.S., has received widespread recognition and nods from the likes of authors Eric Schlossinger and Michael Pollon, whose bestselling books (Fast Food Nation, and In Defense of Food, respectively) drew the connection between food industries and environmental and health problems.

There's plenty of appetite for a serious conversation about food's role in health care. And champions like Carson are making important inroads. But they're also facing some strong barriers.

On a tour of the St. Joseph's kitchen in January, Carson showed me a facility "built from the ground up to basically not cook." She was sort of joking, but not really. This impressively large but mostly empty kitchen at St. Joseph's hospital was built in 2002, ready-made for re-thermalization.

With no ceiling fans, no floor drains and only a small sink, the actual cooking doesn't even happen here; it's done in a cafeteria down the hall equipped with baking ovens and proper ventilation. Food is shuttled to the kitchen to be prepped, portioned and plated. "That's why we're all slim," Carson joked. "From going back and forth. It's quite inefficient."

One thing the kitchen does have is plenty of refrigerator space: a must if you're in the business of buying frozen lasagna, says Carson. And over the years she has managed to convince administrators to add appliances. "For Christmas," she said proudly, "I got a $7,000 food processor."

Carson estimated that 60 to 70 per cent of St. Joseph's operating budget is labour. That leaves just 30 to 40 per cent for supplies, which is typical for most hospitals, she says. Of that, about one per cent is spent on food: a bare-bones budget of $7.43 to cover three meals and two snacks per patient, per day.

"If you think about it, just personally, you could never afford to shop in the frozen aisle section every night with $7.43," she noted. "You would actually have to produce and make your own food."

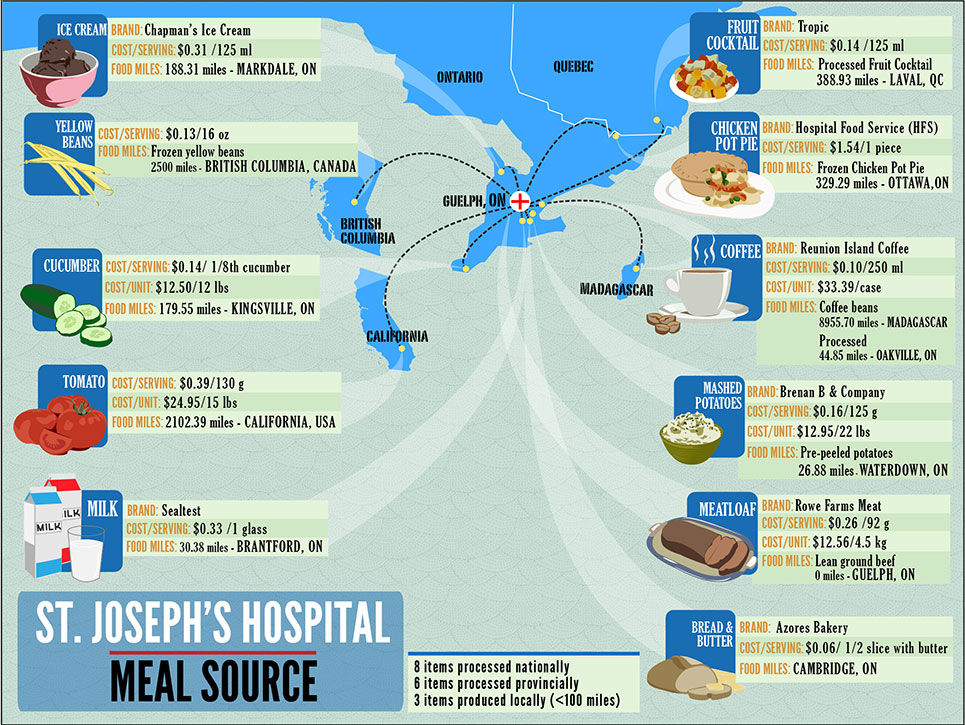

Carson said she prepared simple meals relying on cheaper whole ingredients, buying canned tomatoes and raw onions and garlic, instead of more expensive frozen prepared pasta sauce. Local, hormone-free veal with a baked potato and side salad, for example, is one of St. Joseph's regular dinner options.

There are advantages to buying local beyond better-tasting food, said Carson. She noticed staff morale "go through the roof" when she started introducing more conventional cooking at St. Josephs. "Our cooks are feeling really proud of what they're producing and creating," she said. "That's a huge factor."

Not just healthier, safer too

Working with raw ingredients also made it easier to avoid things like gluten, salt, dyes, allergens or other contaminants that could harm individual patients, said Carson.

St. Joseph's buys lettuce by the head and washes and chops it rather than buy pre-washed and pre-packaged salad, she says. "It's not coming from very far, so if there is a problem the impact is going to be very localized," Carson explained. "But, say you have all the Toronto hospitals buying their lettuce from some supplier in California and there's a problem with salmonella or something. That could be really bad."

Anyone who was working in a hospital or long-term care (LTC) facility in Canada in 2008 knows just how bad. That year a listeria outbreak infected 57 people, killing nearly every second victim. Most of the 22 fatalities were elderly people living in long-term care facilities. In fact, some contaminated deli meats had been packaged specifically for those long-term care facilities.

According to an outbreak analysis by the Public Health Agency of Canada, almost 80 per cent of confirmed cases lived in a long-term care home, or were admitted to a hospital that had served deli meats taken from large packages.

"When all that was happening, I was just sitting in my office not worrying at all," said Carson. "Because we actually buy whole pieces of ham and we slice it ourselves."

'Naturalness' rates low

In early 2012, the Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care produced a report on food service in Ontario hospitals and LTCs that looked specifically at the challenges and opportunities of incorporating local foods. It surveyed 137 food service managers, representing 16.7 per cent of the food service departments in all the hospitals and LTCs in Ontario.

Food services managers placed safety at the top of their priorities (100 per cent). It was closely followed by nutrition (97 per cent); sensory qualities, like texture and temperature (97 per cent); and low cost (88 per cent).

Least important to Ontario hospital food managers, according to the survey, were fairness or fair trade in product sourcing (30 per cent); food origin (24 per cent); and "naturalness" (15 per cent).

The responses also showed that long-term care facilities were already much more likely than acute-care hospitals to practice conventional cooking methods.

Eighteen per cent of acute-care hospital administrators reported using conventional cooking methods for patient meals "most" (80 to 100 per cent) of the time, while 70 per cent of long-term care administrators reported doing so.

Long-term care facilities are more likely to cook from scratch partly because patients are living there for years, rather than weeks or months, and longer stays mean more meals.

"Food in these facilities is often considered more a part of the healthcare experience, whereas in acute care food is sometimes considered secondary to healthcare treatment," explained Brendan Wylie-Toal, Sustainable Food Manager for the Canadian Coalition for Green Health Care.

Bulk and "re-therm" food systems are more prevalent in large urban facilities also partly because it makes catering for 500 to 800 patients a day much easier. "The food quality suffers though," added Wylie-Toal.

While Carson argued that the hurdles to putting something fresh, tasty and local on every patient's plate each day are more mental than financial, in September St. Joseph's Hospital President Marianne Walker told the Guelph Mercury that the facility is facing challenging circumstances this year, in particular due to the rising cost of food and with no increase to its food budget.

She said the facility spends more on food than is allocated by the province -- a figure that is roughly $7.30. "Our plan is to continue with the local food," Walker told the paper. "At the same time, we always have to make sure we stay within budget."

Tomorrow: Why can't British Columbians find out what is in Grandma's hospital food? ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: