[Editor's note: This is the second article in a Tyee reader-funded series looking at B.C. agriculture's reliance on migrant "guest" workers, who those workers are, and what challenges they face. Find the rest of the series so far here.]

The soccer fields around bilingual Ladner Elementary School, in Delta, ring during weekdays with boisterous young voices in both of Canada's official languages. But on summer Sunday afternoons, beneath the gleaming wings of passenger jets passing low overhead on their way into or from YVR, deep masculine shouts of "Pasar!" and "Aqui!" fly across the pitch, as migrant workers, enjoying a day off from local farms, jockey for the ball in competitive matches of futbol.

The first round of the afternoon pits Mexican and Guatemalan teams from different farms against each other. Some wear professional looking jerseys funded by their employers, others defend their net wearing the very same jeans and T-shirt they worked in all week.

Organized by a local pastor, the weekend league provides a respite from days of labouring in fields and greenhouses across the lower Fraser Valley. The matches, followed by burgers and a short Spanish sermon, happen every other Sunday through the summer. They offer a temporary sense of community for workers half a continent away from friends and family, until they can board one those planes for home.

By the numbers

How many are here, and who are they?

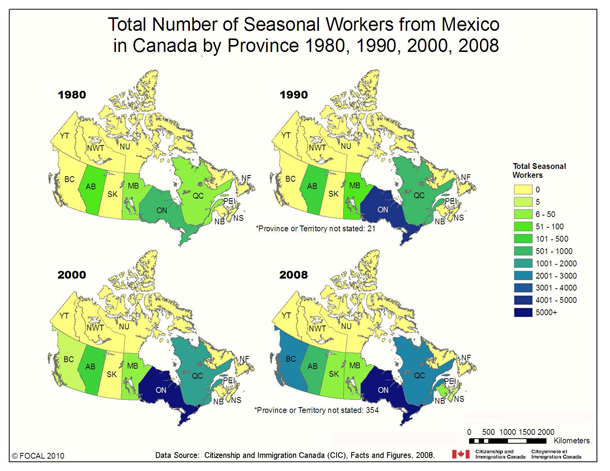

A mere 70 workers came to the province in 2004, the first year that the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP) was available to B.C. farmers. The number of SAWP jobs approved by HRSDC reached a plateau in 2009, and has remained since at about 3,500 positions a year -- placing British Columbia employers slightly ahead of Quebec (3,330 workers) and a distant second to Ontario (18,325) in use of the program.

B.C. farms were allowed to hire an additional 435 workers last year through the "low skilled" agricultural stream of the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP). That number has also grown since 2005, when farmers were only approved to have 11 workers come to the province under that program.

Mexico and Caribbean states can send workers to Canada through SAWP, but last year only nine came from Jamaica, St. Vincent or the Grenadines. Most TFWP workers in B.C. last year (278) were Guatemalan, but Indian and Filipino labourers have outnumbered Latin Americans in some past years.

Overwhelmingly, field hands are male. Federal records reveal that the dozen or so women among BC-bound SAWP workers in 2006 had grown to only 150 by 2010 -- "a minority within an already vulnerable labour force," as Evelyn Encalada Grez, a community organizer and University of Toronto doctoral student, put it in a policy brief reporting that only 2.5 per cent of SAWP workers nationally were women.

Breadwinner's aspirations

With an eye fixed on his flanking teammates, the goalie of one Mexican team hoofs the ball downfield, sending players scrambling.

A group of co-workers from Delta cheer on the action while lounging under the June sun. Every year, these men migrate here to live in a crowded bungalow and labour in sweaty greenhouses, creating futures that would be impossible in much of Mexico's rural agrarian economy.

Few work harder than Ernesto, a slim, fit, 27-year-old father of two from the northern state of Durango who used to cultivate cabbage in Ontario. His strong work ethic has earned him extra hours every week and an independent position at a new greenhouse. This year, he will stay into November, two months longer than everyone else. Working the fields back home, Ernesto sometimes makes less than $10 a day; here, he makes that hourly.

"We use the money in many ways," Ernesto says. "To build a house or make it bigger. You can have a business, you can do other things. But if you stay in Mexico you can't do anything. In Mexico we don't have what we have here."

Ernesto will spend some of his money to improve his house, but he'll also invest in his own land. He wants to expand, and improve has land’s productivity.

New to the program from the state of Oaxaca, Ernesto's shy roommate Javier is focused on paying off some personal debt with his earnings before building a house or investing in any business ventures.

In contrast, the stout, long-haired Rolando has been working at farms across Canada for the past 13 years. Seasons of labouring in Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba have allowed him to build two nearly completed houses and a small fleet of taxis.

Rolando's time away has kept him from his most important investment: his daughter. From a poor rural community near Toluca in southern Mexico, he wants his family to enjoy a better standard of living. Putting food on the table, paying for clothes and school are his main priorities now.

"I talk to my daughter and I always tell her that the reason why I come to Canada is because I don't want her to suffer what I suffered."

Mexico's barren prospects

Now, more than ever, these men say, they value the back-breaking work they find on B.C. farms, work that farm owners can't find British Columbians to do.

In Mexico, the program is oversaturated with applications. Many people applying from his community are rejected, says Ernesto. Mexican workers also have increased competition from Guatemalans, who work hard and are being hired in greater numbers, says Rolando.

"We have to take advantage of this luck that we have," says Ernesto.

After four games, the Mexicans emerge victorious over Guatemala. Revenge will be sought in two weeks. Same time, same place. The competitive spirit, however, gets left on the field, a young Guatemalan player tells us. "After the game, everything goes back to normal," he says, lying back in the sun.

Players eat plates of post-game hotdogs and burgers with the works while they form a congregation around Carlos Carrion, head of the Evangelical Baptist Church's B.C. and Yukon migrant worker ministry. Carrion has provided the meal. In return, he asks the group of life-long Catholics to hear his passionate pitch for the virtues of his brand of Christianity.

Workers stand or sit cross-legged on the grass, listening patiently and politely, but most plainly ready to return to their temporary homes. Still, when Carrion calls for those willing to stand next to him for the Lord's Prayer, a few leave their seats to stand with him.

The good and the bad

Carrion has organized these afternoon respites for the last three years, but he also takes workers to doctor appointments, helps with taxes and bank accounts and speaks to employers on their behalf. During those errands he says has also seen poor housing, breaches of health or safety regulation, and broken contracts. However that's not always the case -- or even the rule.

Some farmers, Carrion said, go to great lengths to help workers, even going so far as to hire a Spanish translator to help communicate during the workday. It might seem like a small gesture, but greenhouse workers we spoke with in Surrey this summer said it was a relief to find translators ready to help clarify their instructions.

"I don't want to say that all employers are bad employers, there are really good employers," said Carrion. "They are taking workers to the doctors."

Father Saul Alba's perspective on B.C.'s farm employers, and the conditions some provide for their workers, isn't as kind.

"We have been to places where the living conditions are terrible," says Alba, a Mexican lawyer turned priest who spent the last 13 years at a diocese in Oregon.

When his U.S. work visa expired last year, Alba took a temporary job delivering Spanish Catholic mass in Abbotsford and Cloverdale. The assignment kept him close to the border so he could re-enter the U.S. quickly when his application for entry went through, but it also allowed him to offer support and spiritual counseling to migrant workers in the area.

During those visits, he says, he generally found his countrymen enjoying comfortable homes, complete with Spanish cable T.V. and air conditioning. However, the less fortunate, he claims, drank dirty water and seldom travelled to town for groceries, instead eating the food they harvest during work.

During one visit to Surrey workers, Alba says that an employer chased him and other church volunteers away with threats, while they were parked on a side road attempting to talk to workers on the other side of a fence.

At another house in Surrey, he says he found workers locked inside their house overnight with chains and locks installed by employers. He doesn't provide an address, but maintains, "They couldn't even go outside, neither [could] we go in and visit them. We had to talk through the gate."

But even in those cases, Alba tells me, it's the only option many workers have to get ahead. So they put up with injustices, work hard and hope to come next year. "You take it or leave it."

Luck of the draw

Once the sermon finishes, players load into the minivans and cars of church volunteers who give them a ride home.

One group of Guatemalan players employed by a major Aldergrove pepper producer lives under the watchful eye of a demanding foreman with little privacy, forced to work at breakneck speeds. Another crew of Mexican workers enjoys a comfortable, furnished home within biking distance to amenities in Delta.

On the soccer pitch, at least, everyone has enjoyed an hour or two of life on a level playing field.

Next Wednesday: Labour unions and B.C.'s temporary migrant workers. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: