The chill of a June evening in Victoria had settled over the ball park. The local squad, an expansion team with the inexplicable name HarbourCats, was down to its final strike.

At bat was Dylan LaVelle, a teenaged prospect from Lake Stevens, Wash. The young man had awakened at dawn to travel to Vancouver Island to join the club, arriving just a few hours before the game's first pitch.

The 'Cats had trailed by 9-1 to the Medford (Ore.) Rogues, but scratched and clawed back. With LaVelle at bat, the home team still trailed the visitors by 11-10. The count was 1-2 when LaVelle stroked a shot to the base of the fence in right centre for a double, two HarbourCats runners racing home with the tying and winning runs.

His teammates, few of whom he had even had a chance to meet, raced from the dugout to mob the latest recruit.

"That was baseball magic," HarbourCats general manager Holly Jones said later. "Those are the kinds of games you see in the movies."

The 'Cats play in the West Coast League, which provides a 54-game, summer playing venue for athletes who compete for American colleges and universities. Many of them will go on to enjoy professional careers. Included on the current roster are the Russell brothers from Victoria. Austin, 21, is an outfielder for Southern Polytechnical State University in Georgia during the school year, while Ty, 19, is a first baseman for Marshalltown Community College in Iowa.

The team is owned by John McLean, the founding partner of a Vancouver venture capital firm. The 'Cats are the third baseball team to try to establish a business in Victoria in the past decade. The Victoria Seals of the Golden Baseball League lasted two seasons, while the Victoria Capitals of the Canadian Baseball League lasted just two months before folding.

The 'Cats have one financial advantage over their recent predecessors -- the players earn no salary, as they need to maintain their amateur status while playing for colleges and universities.

The 27 home games are to be played at Royal Athletic Park, more often used in recent years as a soccer pitch. (It is also home to such events as beer and music festivals.) Top ticket is $15. A glass of craft beer costs $6 and a hot dog with grilled onions goes for just $3. As well, food trucks offer such delectable goodies as curry and pulled-pork poutine. It is a fine way to spend a Victoria summer evening.

So far, attendance has been promising, though not overwhelming. The city is notorious for having walk-up crowds, patrons deciding at the last minute (and after checking the weather) whether to take in a sporting event.

Diamond duels

The summer game has long struggled to establish a permanent presence in the garden city.

The city named for a monarch is more often associated with genteel cricket and old-boy rugby, but baseball's roots are almost as old as the city itself. Over a century and a half, local fans have rooted for teams with such nicknames as Bees, Blues, Mussels, Chappies, Athletics, Islanders and Legislators. From 1952 to 1954, the Victoria club was known as the Tyees, a fine name.

Baseball was introduced to Vancouver Island by American prospectors off to the gold fields.

One of the earliest recorded accounts of a baseball game played in Victoria involved an incident in which two men in a buggy interrupted a match being played in Beacon Hill Park. Words were exchanged. An angry player pulled a man out of the vehicle while brandished a pistol. Bystanders ended the standoff before further violence was committed.

An 1863 match pitted the city's cricket players against proponents of the newer sport. The cricketers prevailed, 40-34.

The formation of the Olympic Base Ball Club at a meeting at the Gymnasium Hall in 1866 marks the formal beginning of baseball in the British Columbia capital. The club's president was James Gillon, an accountant with the Bank of British North America, while other directors included Robert Adams, a hatter, and Joshua Davies, an auctioneer.

The Olympic club exhibited the new sport in matches against cricket players. With any rival team needing to travel by boat to the island, the club often played against itself, having formed a Pretty Boy nine to take on the Ugly Beauty nine.

The Olympics challenged visitors to matches in the years before the colony joined Confederation, including a showdown against the officers of the American frigate Pensacola (won by the locals, 71-46, on the strength of a 29-run sixth inning).

The Olympics unveiled smart uniforms for a game against a team from the Washington Territory in 1869. The Victoria side wore white flannel shirts with a blue letter O on the breast along with white pants with white caps, all with blue trim. The Rainier club of Olympia wore white shirts and dark pants. The Olympics spanked the visitors, 45-23, before entertaining them with a dinner at a downtown hotel.

Cheap seats and sketchy umps

Professional baseball made its debut in the capital city of British Columbia in 1896 when a team called the Chappies joined the New Pacific League. Rival teams included the Portland Gladiators, the Tacoma Rabbits and the Seattle Yannigans (also known as Rainmakers). The players competed for a $100 silk pennant donated by Spalding, the American sporting goods manufacturer.

The Victoria team was supported by business interests who saw the sport as a means of promoting opportunities in the city.

A report from Portland described the Oregon city covered in posters hailing games against what was then British Columbia's largest city.

"As a matter of fact there is nothing so advertises a city, especially in the United States, as a good baseball club," the Victoria Daily Colonist said. "The result of each day's game is telegraphed everywhere by the press associations, and the weekly sporting papers add to this publicity by publishing weekly letters from the cities supporting league clubs."

The Chappies played home games at the Caledonia Grounds on Niagara Street in James Bay, just west of Beacon Hill Park. Admission to the grounds was 25 cents, while a seat in the grandstand cost an additional 15 cents.

The first professional game was played on May 20, 1896. The Fifth Regiment band led a parade to the grounds. The Portland players, wearing black and white uniforms, led the way, followed by the Chappies. Spectators along the parade route joined in the march to the grounds, where Mayor Robert Beaven, a former premier, was given the honour of throwing the ceremonial first pitch. It was customary then for a batter to swing at the pitch. Gus Klopf, Victoria's playing manager and third baseman, managed only to pop the ball into the air.

The first professional game in Victoria also induced the first local criticism of a game's arbiter.

"Umpire (Frank) March would make a splendid mariner, as his stentorian tones could be heard in a gale without the aid of a (ear) trumpet," the Colonist noted. "Would that the accuracy of his decisions were in keeping with his vocal powers."

The Chappies enjoyed a comfortable 5-2 lead going into the late innings when disaster befell the team. Klopf had a rough game. He was shaken up when a Portland runner crashed into him on a steal attempt. Then, in the seventh inning, after he smacked his third hit of the game, Klopf stole second base, only to be struck in the head by the thrown ball. The player writhed on the grass. "After a short interval," the Colonist reported, "Klopf was apparently revived, although he reeled rather than walked towards the players' bench." He was examined by Dr. John S. Helmcken, the first medical officer at Fort Victoria who, at 71, was the province's best-known physician. The doctor urged Klopf to call it a day, but he returned to the field only to commit the error that led to a 8-7 defeat.

"It was reported last evening that Capt. Klopf was dangerously ill," the newspaper stated. "Fears are entertained that he is suffering from concussion of the brain."

Klopf would survive, though the Chappies and the New Pacific League soon after foundered.

Where legends were made

Pro ball disappeared until the new century, when another franchise began play in 1905 in what is now Windsor Park in Oak Bay. That squad is remembered mostly for providing brief employment for first baseman Hal Chase, who went on later that season to join the New York Highlanders (later the Yankees). Chase is regarded as the most notoriously crooked player in the history of the game.

After a six-year hiatus, pro baseball returned to the capital with the creation of the Victoria Bees in 1911. The club signed a fleet outfielder who was the son of prominent Washington state judge E.C. Million. The judge's wife indulged her eccentricities, naming the son Ten, as in Ten Million, which in those days was a name and not yet a baseball salary. (She also convinced her son to name his daughter Decillion, which has 33 zeroes if you're keeping score at home. She was known as Dixie.) Ten Million hit a solid .276 for the Bees and signed with Cleveland of the American League, though injuries prevented him from ever playing in the major leagues.

In 1914, a promising teenager from San Francisco named George Kelly made his professional debut after signing with the Bees. The first baseman stood 6-foot-4, a giant in his day, earning him the memorable nickname High Pockets. He hit so well he got a mid-season call up by the New York Giants the following year. Kelly hit .297 in a 16-season major-league career and was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1973.

The best homegrown athlete ever to come from Victoria was Doug Peden, who won a silver medal for Canada as a basketball player at the 1936 Olympics. He teamed with his older brother, Torchy, to become champion cyclists, specializing in six-day races, a grueling marathon popular as cheap entertainment during the Depression. In 1941, Doug grew his whiskers long to join a barnstorming squad sponsored by the House of David, a religious commune that promoted its cause with the traveling troupe of bearded and long-haired players. After the war, Peden kicked around the Pittsburgh Pirates system, hitting as high as .360 for the York (Penn.) White Roses in 1946. Peden eventually returned home to be the sports editor of the Victoria Daily Times.

In 1949, another San Francisco-born player made a mark in Victoria. Gil McDougald, played 140 games, leading the team in average (.344) while hitting 13 home runs. Two years later, he was named American league rookie of the year, the beginning of a stellar career with the powerhouse New York Yankees.

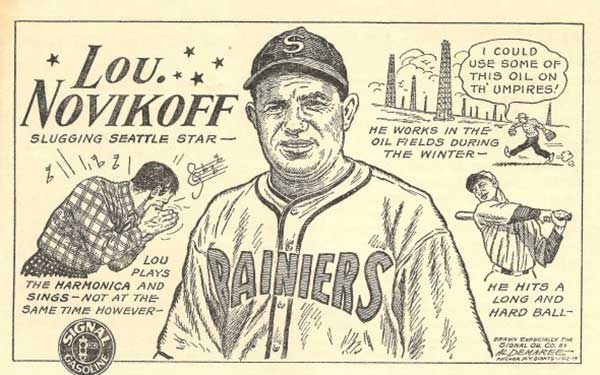

In 1950, a legendary baseball character wound up his pro career with a brief stint in Victoria. Lou Novikoff was an affable longshoreman and oilfield roughneck known on the diamond as the Mad Russian. He gained a following when sportswriters recorded his eccentricities -- harmonica playing, spontaneous singing, outbursts of Russian oaths, indifferent fielding -- while playing for the Chicago Cubs, whose ivy-covered wall at Wrigley Field he considered poisonous. He refused to chase balls landing in the shrubbery. When a teammate sought to allay Novikoff's fears by rubbing ivy leaves over his body with no ill effect, the Mad Russian asked, apropos of nothing, "What kind of smoke would they make?"

And Bill Murray too

The wackiest team in all of Victoria's baseball history took to the field in 1978. Two baseball-loving owners maxed out their credit cards to buy an expansion franchise in the Northwest League, a single-A circuit with such rival clubs as the Boise Buckskins, Grays Harbor Loggers and Walla Walla Padres. They named their new team the Victoria Mussels, later commissioning an artist who created a logo featuring a bicep-flexing bivalve mollusk.

"It was probably the first stupid name of all time," owner Jim Chapman once told me. "We were the initial idiots on that bandwagon."

A crew of rejects and castoffs wound up at Royal Athletic Park, including a pitcher with a reputation for doctoring the ball, another desperate to learn the knuckleball, and a first baseman better with his impression of John Wayne than of Lou Gehrig.

The most famous player on the roster played but a single game in 1978. The comedian Bill Murray, known then for his role on Saturday Night Live, signed a one-day contract, suiting up for the Mussels to razz the umpires and play to the crowd. He even managed a bloop single before the umpires tossed him from the game.

As an act, it was an amusing preview of his screwball performances in movies such as Caddyshack. As a promotion, it was a failure. The game failed to sell out. The Mussels averaged fewer than 250 fans per game. They were truly Victoria's secret.

Too bad. The lanky kid learning the curveball was Tom Candiotti, who went on to enjoy a 16-season big-league career; the slugging first baseman who did impressions was Danny Gans, who went on to fame as an impressionist in Las Vegas, where he played nightly for crowds five times as large as those the Mussels drew; the pitcher who doctored the ball was Dale Mohorcic, who finally made the majors as a 30-year-old rookie. Once, an umpire frisked Mohorcic looking for a foreign substance. He found nothing. After the game, the pitcher complained of a sore throat -- he had swallowed a strip of sandpaper.

You can look it up. ![]()

Read more: Travel