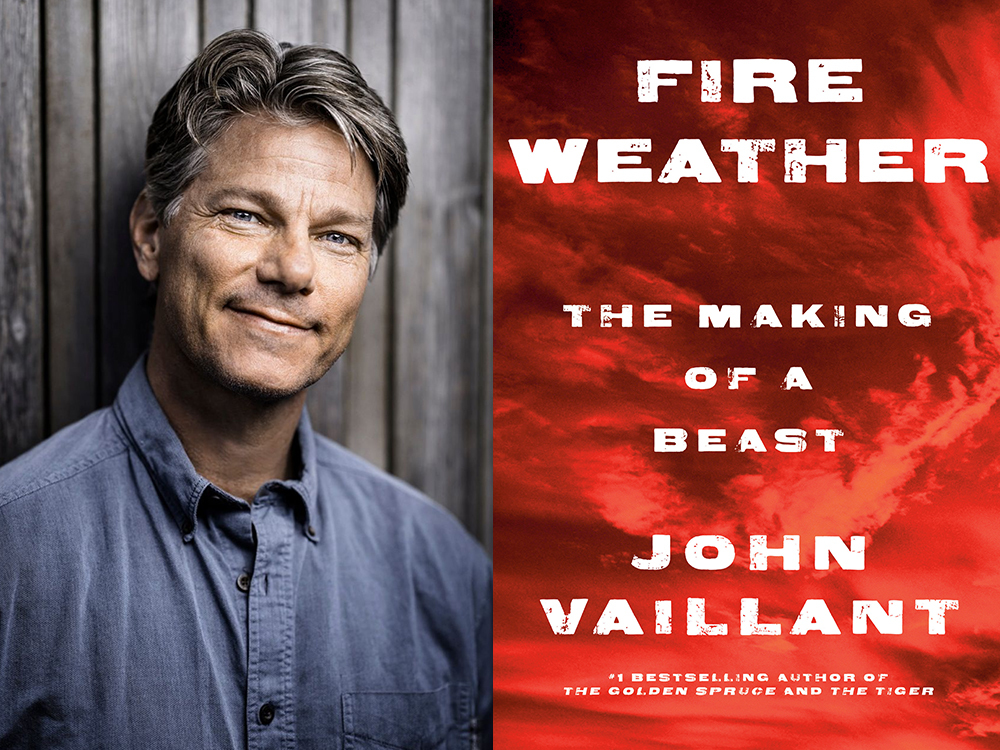

- Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast

- Knopf Canada (2023)

Acclaimed author and Vancouver resident John Vaillant’s new book focuses on one day in May 2016, in the small city of Fort McMurray, in northern Alberta. But from there it sweeps two centuries into the past, around the world to California, Europe and Australia, and brings us back to our own hot, smoky spring and ominous future.

It is a fast-paced narrative of a disastrous wildfire and of the culture that both created the fire and was damaged by it. And it is a brilliantly written description of our own insights and follies: we saw the present disaster coming long ago. We could have prevented it, and we let it happen anyway.

One of the themes running through Fire Weather is the “Lucretius Problem.” Lucretius was a Roman poet and philosopher; in his book On the Nature of Things, he observed that we can’t imagine a river any bigger than the biggest river we’ve personally ever seen.

“In essence,” Vaillant explains, “the Lucretius Problem is rooted in the difficulty humans have imagining and assimilating things outside their own personal experience.” This was true of the people in Fort McMurray on the morning of May 3, 2016, and it is equally true of us as we contemplate the catastrophe we are bringing down on our own heads.

In Fort Mac that day, Fire 009 was just one of several around the city. It had survived water-bombing and grown overnight, but local officials were hesitant about its seriousness. The region had seen many fires in the region over 50 years, but none in Fort McMurray itself. The officials advised their community to carry on but have a plan. Neither officials nor community could really believe it would happen now. The Lucretius Problem made such an event literally unthinkable.

Vaillant offers an anecdote that shows how the Lucretius Problem operates. A resident drops off some items for Sam the dry cleaner:

… and while I’m standing there, a guy comes in from the golf course in full golf apparel, and he’s like “Holy shit! We just got evacuated from the golf course!”… And he says, “Well, I’m here to pick up my dry cleaning.” I said, “What golf course are you on?” — because we only have two in town. He says “Thickwood,” meaning the fire has just jumped the river.

… Sam the dry cleaner, who’s our buddy, is like “Whoah!” And he’s on the phone to his wife: “Honey, it just jumped the river — get out, get out, get out!” … In all this craziness, Sam takes my stuff, logs it, and he’s like, “Tuesday good?” I’m like, “Yeah, Tuesday’s great.”

Long foreseen, often forgotten

Even with the evidence before us, we lie to ourselves that it won’t be as bad as the evidence predicts. Vaillant interweaves the Fort Mac fire with a concise history of climate science that was on the right track from the start but was repeatedly ignored or forgotten.

Scientists in the late 19th century calculated that coal-burning industries were already pumping more CO2 into the atmosphere than natural processes could remove. In 1901, one of them became the first to use the metaphor of a greenhouse. In the 1930s, a Canadian-born engineer named Guy Callendar argued that CO2 had warmed the atmosphere by 0.5 C between 1890 and 1935. Later studies showed he was right.

Another Canadian, Gilbert Plass, proved in 1953 that water vapour and CO2 trap solar heat in the atmosphere. A prominent oceanographer, Roger Revelle, testified before a U.S. congressional committee that burning coal, oil and natural gas was warming the planet. He got a respectful hearing from conservative congressmen.

In 1959 Edward Teller, the father of the H-bomb, got an equally respectful hearing from oil and gas executives at a symposium on the campus of Columbia University. Teller was there to blue-sky about the future of energy and speculated about using nuclear bombs to gain access to resources like the tarsands of northern Alberta.

But the petroleum industry would need to find other energy sources, Teller warned the executives, because putting more CO2 in the atmosphere would result in melted icecaps and the flooding of coastal cities like New York.

Nuke the tarsands!

The stunned executives didn’t know what to make of this prophecy; Vaillant says they took only what they wanted to hear from Teller’s ideas, and one oil company went into discussions with Alberta’s Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board to detonate a nine-kiloton atomic bomb in the tarsands around Fort McMurray. Alberta premier Ernest Manning loved the idea, but it was eventually dropped out of fears of Soviet espionage.

Climate change itself was dropped again and again: after a few media reports, it would fade out of public memory. Even the oil companies did serious research that confirmed earlier climate science and explored alternative energy sources.

But they too seemed to forget about it — and then funded massive disinformation campaigns to throw doubt on the whole idea. Vaillant cites an expert who describes the petroleum industry’s strategy as “predatory delay:” “the deliberate slowing of change to prolong a profitable but unsustainable status quo whose costs will be paid by others.”

This long and complicated history helps to make sense of the Fort McMurray fire. Even as the science (and insurance companies) confirmed global warming caused by fossil fuels, we consumed ever more of them. Vaillant notes that modern homes (including those in Fort Mac) are essentially various forms of oil. Firefighters call vinyl siding “solid gasoline;” carpeting and furniture are made of synthetic fabrics. When such a house begins to burn, many of its contents give off inflammable gases that explode in a “flashover.”

“The houses stop being houses,” Vaillant writes. “They become, instead, petroleum vapour chambers.”

The outsides were no better: wood-chip pathways became fuses leading to the houses, and garages often sheltered big trucks and cars with big gas tanks — as well as propane tanks. And houses were right on the wildland-urban interface, with thousands of trees nearby.

Burning to the ground in five minutes

For the Fort Mac firefighters, houses were now liabilities rather than assets. Under these conditions, a house could burn to its foundations in five minutes. A whole street of houses could explode, sending burning debris to the next street. To save one house, it became necessary to bulldoze three or four others before they could ignite.

One of the most striking aspects of the Fort Mac fire is that no one died in it. Two persons died in an auto accident while evacuating, but 88,000 people got safely away in a matter of hours — on a notoriously dangerous highway. It was a remarkably disciplined impromptu exodus.

And while Vaillant doesn’t mention it, the fire refugees got a remarkably impromptu welcome by communities with few resources: free food in any diner, free shelter complete with fresh diapers if needed. Some people even ran a service delivering jerrycans of free gas to vehicles that had run out of fuel. We would later see something similar on a national scale early in the pandemic when governments suddenly abandoned their neoliberal principles and provided emergency support for millions of Canadians whose jobs had suddenly vanished.

Vaillant is wryly aware of the overuse of the word “unprecedented” during the Fort Mac fire and since then. The precedents for Fort Mac were the Chisholm Fire in 2001 and Slave Lake in 2011. Fort Mac itself was the precedent for other fires Vaillant describes from Australia to California. These events are unprecedented only to those who couldn’t imagine them until they themselves were personally affected. It’s as if we all have to solve the Lucretius Problem the hard way.

Defiant denialism

Recently Vaillant published an op-ed in the Globe and Mail about the current wildfires in Alberta. Some of the article’s commenters would make Lucretius himself shake his head. Seventy years after Gilbert Plass, many of us remain defiantly denialist — so many that in the imminent Alberta election, climate change has scarcely been mentioned.

We’re little better here in B.C., exporting liquid natural gas and Fort Mac dilbit while building Roberts Bank 2 to move goods from fuel-burning ships to fuel-burning trucks and trains.

John Vaillant describes wildfire’s ability to expand and consume as very much like unregulated free-market capitalism. He draws parallels with the Hudson’s Bay Co., which co-opted Indigenous peoples into supplying beaver pelts that would pay for muskets and other trade goods, while damaging the ecosystem in the process. And while Fort McMurray has rebuilt, many have not returned, and bitumen is not selling as well as it once did. It’s harder for oil projects to get insurance — and investors.

Vaillant ends his book with the discovery of “revirescence,” the return of life to fire-blasted land. The forests are reviving around Fort McMurray, and in the ashes of its Abasand neighbourhood Vaillant saw tulips blooming.

“Human beings planted those flowers,” he writes, “with no idea what was to come. This — devoting our energy and creativity to regeneration and renewal rather than combustion and consumption — is what Nature is modelling for us and inviting us to do.”

Read an excerpt of John Vaillant’s ‘Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast’ on The Tyee. ![]()

Read more: Books, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: