If you’ve ever dreamed of actress Tilda Swinton whispering in your ear, then hurry thyself down to Granville Island to partake in two outstanding virtual reality productions at Boca del Lupo’s digital salon.

Goliath: Playing with Reality is a critically acclaimed VR experience that picked up a number of awards. After premiering at the 2022 Venice International Film Festival, it won the festival’s sought-after Grand Jury Prize for Best VR Immersive Work.

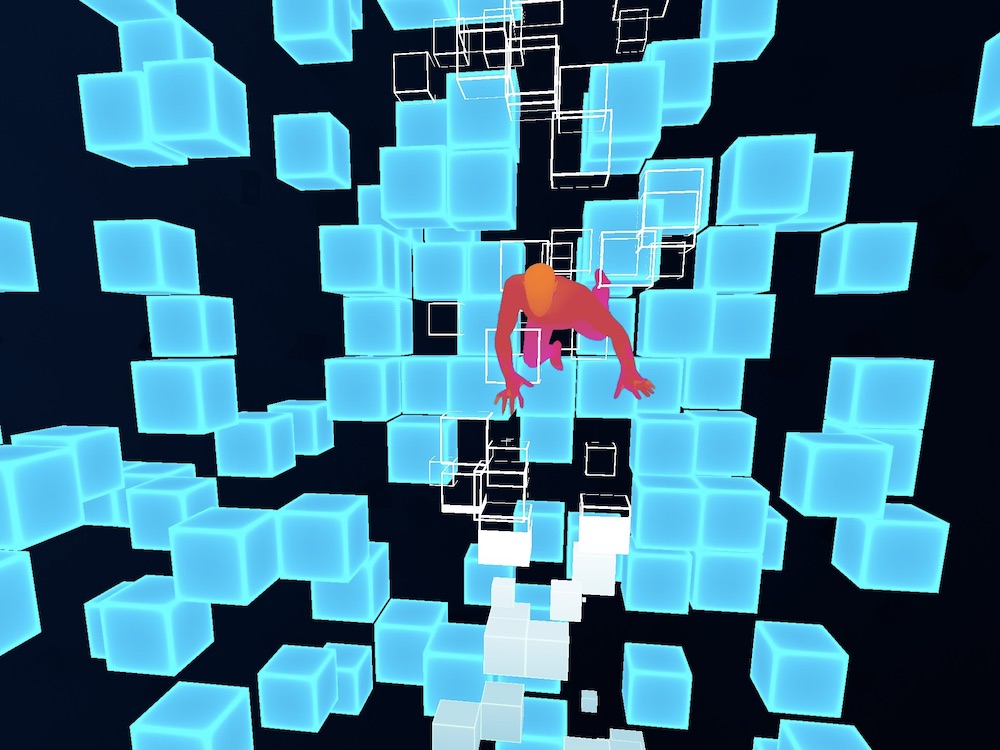

Directed by Barry Gene Murphy and May Abdalla, the 25-minute Goliath takes viewers into the life and mind of a man living with schizophrenia. As the protagonist explains, his return to a place of wellness was precipitated by, of all things, video games. As an inveterate non-player of video games, the interior world of Goliath is distinctly foreign to me, but other folks (like the younger set) will no doubt be deeply familiar with the conventions of the genre.

One of the interesting things that Goliath does is to make viewers’ hands a key part of the interface with the narrative. Except that they’re both real and not real: they’re simultaneously your hands and not your hands. Bear with me for a moment. The digital recreation is so convincing that it’s easy to forget that the glowing green digits that one can control are only a manifestation of technology at work.

At certain points, one is required to tap different controllers, shoot at stuff, fiddle with a joystick and press different buttons. The struggles the character faces are sometimes represented in the form of an arcade game. In taking direct action (i.e., shooting down problems), he is able to enact a kind of control over the chaos of his situation.

Confession: when it came to shooting stuff, I completely misunderstood what was required and had to take off the headset and ask for help. But don’t let the technology dissuade you. If you can figure out the few more interactive requirements, you can easily navigate the story.

So, what’s the story, then?

As a young man, Goliath’s dabbling with alcohol and drugs soon expanded into more destructive habits. Years spent in mental health facilities left him alone and unmoored from social contact. In this aspect, the ability of VR to suggest a constantly shifting mental landscape is ideal. To great effect, the production plays with our understanding of where the real world leaves off and where the imagined internal landscape takes over. The concept of being inside the mind of someone in the midst of a psychotic break is handled in a few different ways. In some instances, passing the controller over garbled sounds turns them into coherent sentences.

Story is where VR stuff has historically lost me. All the flying doodads are interesting enough, but constructing a compelling and ultimately impactful narrative requires something more. To its credit, Goliath offers a thoughtful evocation of what it feels like to be inside the mind of someone experiencing mental health challenges.

In their statement about the work, the two creators explain that the technology is a means to a greater end: “We immerse users in a world where things aren’t as they seem in an effort to unpack our preconceptions and prejudices around mental health and the shame engendered by psychiatric disorders.”

Tilda Swinton voices the narrator named Echo in the production. Her cool delivery is ideal for this story, as she calmly leads participants through a whirling, discombobulating world of dealing with a changing mental health landscape, as well as the camaraderie and friendship that is central to the online gaming community.

The bigger question is whether VR lends itself to empathy in a different way than other media. The answer is maybe, followed by a heavy question mark. With its first-person shooter drills often seen in online games, Goliath relies heavily on already established VR tropes, such as the vertiginous disappearing floor and zippy stuff flying in from all directions.

It’s dazzling, but does all this whirling technology distract from the very human story in the centre? Thankfully no. Goliath never loses sight of human pain, even as it examines rather lofty questions of what reality actually is: ostensibly, we’re all just making it up in our minds.

I almost wish there had been slightly more of this exploration that questions the very nature of reality in the production, since that’s where the technology itself does interesting stuff.

But before things get too meta, Goliath traces a redemptive arc that ends in a fascinating resolution.

Inviting audiences to feel

Directed by Singing Chen, The Man Who Couldn’t Leave is an emotionally laden VR experience that tells the story of political prisoners on the Green Island Prison during the White Terror of 1950s Taiwan. After martial law was declared on May 19, 1949, a period of brutal oppression took place against ordinary Taiwanese people that included mass executions and enforced incarceration of anyone suspected of being a dissident.

Political detainees were entombed alive on the island prison. Cut off from family and friends, they relied upon each other to endure their time in jail. The VR situates viewers directly into the prison barracks, as the men find different ways of coping with the uncertainty, fear and despair of their imprisonment. An elderly man named A-Kuen narrates his own story, as well as those of his fellow prisoners, leading viewers through the enclosed space with minute attention to detail.

As he introduces each of his fellow prisoners, he explains that each individual has found different ways of maintaining their humanity in the face of repression and suffering. Some men (in the pretense of reading) are actually copying banned books. Others play chess. A-Ching, the titular character of the piece, writes letters to his wife and young daughter explaining what is happening, and expressing his desire to return to their life together.

Meanwhile, A-Ching’s wife waits at home, desperate for any scrap of news. She sews a long shirt for her husband and asks him to wear it so that she can recognize him when they finally meet. The long shirt has a critical role to play.

In the director’s statement, Chen explains that the story for The Man Who Couldn’t Leave was based on documents from real political dissidents. It goes deeper than merely a depiction of the men and their plight, plunging viewers into a deeper engagement with the emotional content at the centre of the story.

As Chen explains: “It also lets its audience feel the suffering and hopes of these people and conveys their desires for a better society; hopes that transcend history as universal values pursued by identity groups and new generations. In the end, it is only if stories are constantly told and the ideals and sacrifices of earlier generations are remembered, can the dead souls rest in peace and the spirit of an ideal society can be continued from generation to generation.”

While the profound, often unbearable weight of tragedy is impossible to escape, fragile bits of hope coalesce in the form of protests, marches and songs.

The long line of people defending the idea of freedom takes shape in a seemingly unending procession of ordinary people, armed only with courage, songs and the occasional umbrella standing up to jackbooted authorities.

Both ‘Goliath: Playing with Reality’ and ‘The Man Who Couldn’t Leave’ will be presented at the Boca del Lupo VR Salon Fishbowl at 1398 Cartwright St. (on Granville Island, Vancouver) from May 24 to 28, 2023. ![]()

Read more: Health, Media, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: