“Mouthpiece” is a strange word. If you look too long at it, all kinds of things begin to emerge. Not just tongues, lips and teeth, but other stuff as well, things like innuendo, lies, false oratory, all the things that people say but don’t mean and vice versa.

It’s a fitting title for the most recent exhibition at the New Media Gallery in New Westminster, which takes as its informing idea “the complexities of the human condition through fragmented bodies and the human voice.”

No one holds up a mirror to the human propensity to dissemble and disassemble quite like Tony Oursler, one of four artists whose work features in Mouthpiece this season. Oursler, now 65, is a renowned multimedia artist based in Manhattan.

Oursler has a particular knack for provocation. It’s a quality that New Media Gallery curator Sarah Joyce is well acquainted with. When Joyce was working at the Tate Modern gallery in London, one of Oursler’s installations had a habit of causing a ruckus. His piece, The Most Beautiful Thing I’ve Never Seen, comprised a figure seemingly trapped under a ratty old couch. It literally called out to gallery attendees. Attracted by its cries, loads of people assembled, only to have the human-looking entity begin to abuse them with muttered statements and deprecations.

Although Oursler’s five “AI b0ts” in residence at the New Media Gallery aren’t quite as outwardly disruptive, their ability to unsettle is equally sharp.

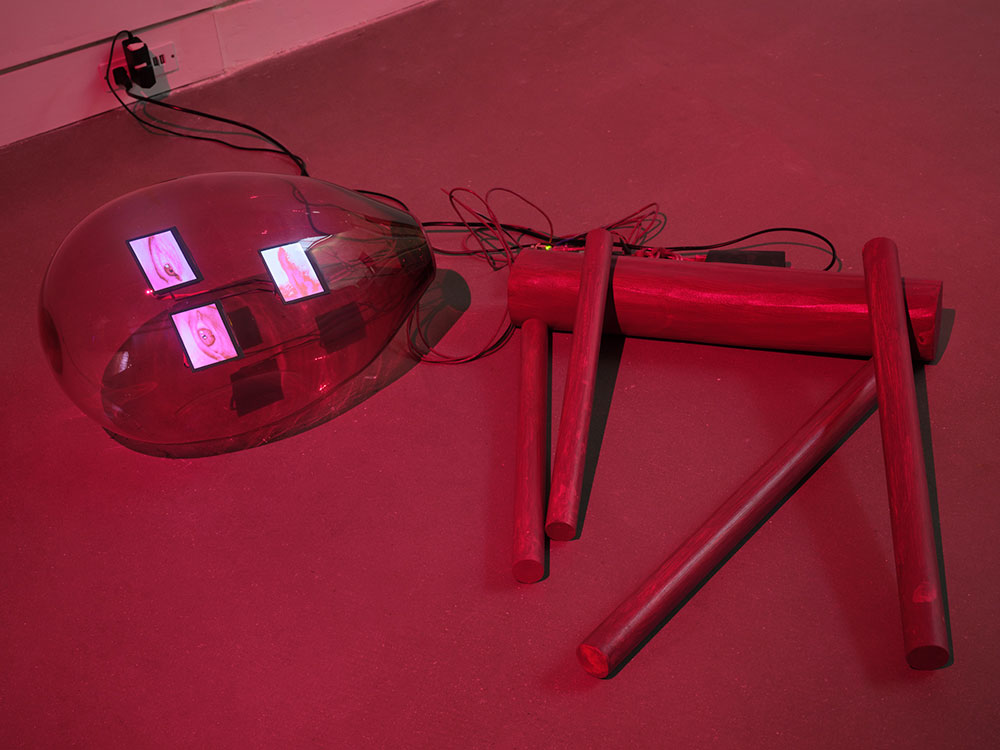

2§ba, !nk, Olo and Snakehead, all hailing from the artist’s 2019 series, are some strange-looking entities. Composed of vitrine-like glass heads with miniature LED screens for eyes and mouths, they are purposefully made to look crappy, with exposed bits of wire and bad paint jobs.

This lack of attractiveness serves a couple of different functions. In their homely state, the "b0ts" draw you in, demand sympathy, pity even, and then when you least expect it, whisper something distinctly odd.

Each of the individual pieces have a different emotional flavour and posture as well as colour schemes — purple, acid green and brick red. !nk lies prone on the floor like an abandoned toy or a beaten dog. The badly painted chunky blocks of wood that make up its body are splayed out like someone cut its strings. It is hard not to feel sorry for the poor thing, as it looks sadly up at viewers, like it has lost the will to live.

Snakehead is a very different creature. Acid green and sticky black, complete with a serpent’s tail, it offers up a repast of different cultural references, everything from snaky enticers and the tree of knowledge to street gangs.

As an early adopter of video art, Oursler began working with technology in the 1970s, freely combining different forms of media. Some of the characters who contribute their lips, eyes and teeth to his work have long collaborated with the artist, but the words themselves come from Oursler.

Taken collectively, the different “b0ts” offer up a chocolate box of human behaviours and reactions filtered through the realm of technology. These stick-figure facsimiles are imbued with both pathos and grotesquery, much like real human beings. Which is maybe why they’re so hard to take in. There is something slightly icky in disembodied mouths with tongues emerging at regular intervals to take a sticky swipe.

In interviews, Oursler has stated that his work is, in part, a reaction to the idea of technology outstripping its creators. Meaning us human types.

In this aspect, our reliance and obsession with technology and information isn’t unlike a new religion. And like any faith, this dependence requires a suspension of logic and blind adherence to the creed. But whereas shiny new iPhones carry with them an allure and tech sexiness, the “AI b0ts,” with their clunky appearance seem, at first glance, more benign. But are they? What agenda is at work? Maybe the source of unease that they invoke, the combination of repulsion and fascination, comes from this convergence of things we like (technology) and things we don’t (ugly paint jobs).

The ordinary stuff of human interaction, mediated through technology, has already resulted in some deeply strange outcomes. But Oursler is clear that the worst might be yet to come as he stated in an earlier interview with Artspace magazine: “One thing I have noticed is that by being so-called ‘connected,’ the aspirational aspect of new technology — or the level of advertising and fantasy space put into aspirational capitalism — has had a really dark effect on people. In other words, everybody expects to win the lottery or have a certain amount of luxury goods that is ever expanding. There’s a gluttonous quality to the endless stream of information that we have — it’s kind of an amplification of the seven deadly sins.”

With AI, a divine epiphany?

A poignant response to Oursler’s predilection for human darkness arrives in the form of The Prayer, a complementary work on view at the New Media Gallery.

Boston-based artist Diemut Strebe worked with scientists at MIT to construct a machine after the prompt, “How would a divine epiphany appear to an artificial intelligence?”

With its disembodied mouth reminiscent of a blow-up doll, it is not the loveliest of creations. In this it shares some of the same anatomical lugubriousness as Oursler’s bots. But what is more critical are the words coming out of its mouth.

Drawn from a wide array of religious texts, Strebe and her MIT collaborators used a neuronal machine-learning software to turn written language into spoken words. They drew from the Old Testament, the New Testament and the Mayan Book of the Dead, among many other works. The installation employs AI tools able to synthesize the rules of grammar, the meaning of the words, as well as other things necessary for sentence construction and oratory expression. The text is lip-synced to the movements of the animatronic mouth with mechanical precision. The sibilant click and whir of the servos that open and close its thick, rubbery lips adds another unsavoury layer.

But something very odd happens when the words are excerpted and run together like a madhouse screed. The meaning, the significance, the loaded aspect that humans assign to scripture is gone, replaced by Amazon Polly’s “Kendra” voice for American English. The barrage of words strung together in patterns sound like they should make sense, but often they simply don’t. The meaning is exempted out of them, so that they become hollow and empty, like an echo chamber.

As New Media Gallery curator Sarah Joyce explains, no one has reacted to the repurposing of holy writ during the exhibition’s run so far. Which is kind of strange, given how deeply held religious texts tend to be.

Watching The Prayer in action, a quote that I’d read earlier popped up unbidden, about how anyone who had read the Bible in its entirety didn’t believe it by the end. A close reading of scripture demonstrates what most reasonable people already know: that it’s a conglomeration, a mishmash of different voices, different authorial styles, all smooshed together. If you’re hoping for a heavenly chorus of order and harmony, good luck sucker.

Bittersweet symphony

If you would like to witness what such an unholy choir might look like in the flesh, then take a gander at Bad Mantra.

At first glance, the piece doesn’t look all that frightening. It resembles a music recording studio from the white brick facade to the brightly lit interior, where pink, fuzzy puppets are cheerfully singing and plonking about on different musical instruments. But as Joyce explains, the piece seems to terrify younger children, who often refuse to step foot inside the installation.

The artists Nathaniel Mellors and Erkka Nissinen, both musicians themselves, designed the piece — its blinding white walls, precise squares of blue carpeting, the bad stitching on the tumorous mass of puppet heads affixed to the wall — with painstaking precision. From this John Carpenter-esque meltdown of eyeballs and flapping mouths, a series of wormy arms loop out and around, boring through walls, each individual limb ending in front of a different musical instrument. Keyboards, guitar and a mixing board are alternately plonked, strummed or fumbled at. The resulting cacophony is a nightmare of off-key sounds. So, maybe the kids are on to something.

The piece originated from a work presented at the 2017 Venice Biennale, entitled The Aalto Natives, which shares some of the same characters as Bad Mantra.

Having watched the video work that inspired the installation, I am at a loss as to what to say exactly. It’s alternately funny, horrifying and extremely freaky-deaky. But taken collectively with the other works in the show, a larger narrative begins to emerge. The three different installations take many of the things we love and revere and effectively turn them on their heads.

Faith in technology, faith in art and even faith in faith is exploded. Instead of coherency, there is chaos, and a fracturing, even an obliteration of meaning. It’s both glorious and terrible. Go and see it.

'Mouthpiece' runs until Dec. 11 at the New Media Gallery in New Westminster. ![]()

Read more: Art, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: