- Yes to the City: Millennials and the Fight for Affordable Housing

- Princeton University Press (2022)

“NIMBYs? They’re nothing more than privileged homeowners who hate the poor, hate new buildings and transit lines, hate people parking in front of their houses — all in all, hate any kind of change that might alter or inconvenience their idyllic neighbourhoods in the slightest!”

“YIMBYs? They’re not real activists — they’re just shills for real estate developers, libertarian free-marketeers, brash tech bros and gentrifying interlopers who are making communities more expensive!”

Sound familiar? Anyone who’s tuned into housing discussions in their expensive cities will recognize these battle lines, drawn between groups with competing visions of what the future of their communities should look like.

The YIMBY solution to the housing crisis: a dramatic boost of new homes.

It’s a prospect that’s captured the interest of subsets of politicians, environmentalists and housing providers, from private developers to non-market providers alike. But it’s also one that’s worried “supply skeptics.” In a market where housing is increasingly traded as assets, wouldn’t building more just add fuel to the fire?

The YIMBY movement — which stands for Yes In My Backyard, a counter to Not In My Backyard NIMBYs — is still a relatively young one. In 2013, the movement took off in San Francisco, a city plagued by high housing costs in the wake of its tech boom. One of its first members was a math teacher named Sonja Trauss, who would go on to become a figurehead of the movement. From there, YIMBY ideas gained traction in other expensive cities like Vancouver, with groups like Abundant Housing forming and politicians declaring their YIMBY values.

For Vancouver journalists like me covering the housing crisis, YIMBY ideas have made politics more complex, but also more confusing. (Not to mention ugly. Enter the fray of housing debates on Twitter and you might be called a liar or receive personal attacks.)

Are YIMBYs progressives? When I spoke with then-housing minister David Eby earlier this year, even he noted the progressive split on this issue. Is it more progressive to permit new homes or reject them if it means private developers will profit? To confuse matters further, each advocacy group seems to have their own definition of what the YIMBY label means.

Sociologist Max Holleran has arrived with a timely book called Yes to the City: Millennials and the Fight for Affordable Housing to help dissect the YIMBY movement.

Battle in the backyard

Holleran’s book focuses on American cities, with detours to Australia and the U.K., but the general story is the same in Canadian metropolises.

It goes something like this. Your city becomes a desirable place to live. Central neighbourhoods where it was once possible for middle-class locals to buy homes are now too expensive for workers making average wages. Your city is used to developing new housing on undeveloped land, which is running out, and needs to consider densifying existing communities.

But homeowners who own land in those amenity-rich neighbourhoods near the urban core don’t tend to like change. “Not in my backyard,” they might say. Their long presence in the community — as vocal property owners with experience pushing back against city planners and politicians calling the shots — gives them political clout. Some do so under the banner of neighbourhood organizations for a layer of legitimacy.

Enter the YIMBYs. According to Holleran’s research, they are mostly under 40, setting the stage for a generational battle. Millennials are coming of age as housing is increasingly commodified, trading more of their income for less security than their parents had. They’re tired of paying high rents and prices in a competitive market for homes that are too at-risk of eviction, too small to live in and too far from city centres. Their proposed solution: for cities to build their way out of the housing crisis.

As for what to build, they don’t really care.

“Build more of everything,” say YIMBYs. And that goes for public housing all the way up to luxury condos — putting them at odds with other housing activists who worry that more expensive new housing builds will displace vulnerable populations.

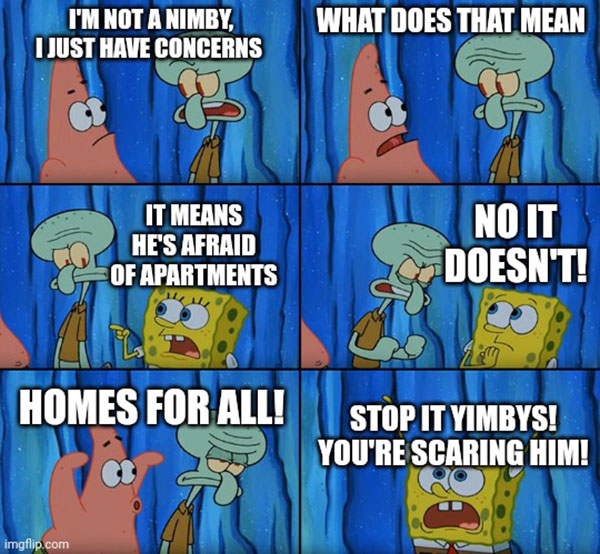

Just as Thor has Loki and Batman has the Joker, YIMBYs are naturally pitted against change-resistant homeowners. They don’t like to be called NIMBYs though, because they say it’s “prejudiced.”

Nimbyism has become enough of a roadblock to new housing — social housing in particular — that senior governments have begun researching how to counter change-resistant homeowners to help municipalities. One provincial report mentions that NIMBYs tend to be older, white homeowners with views that don’t represent the communities they live in. But because homeowners have historically done such a good job swaying their politicians to say no to just about any kind of change, the neighbourhoods they live in have become “bucolic hamlets of wealth within the hearts of cities,” says Holleran.

When NIMBYs come out to say no to new housing, they roll out the same few arguments. They might agree that it’s a good project, but that it doesn’t fit the character of the neighbourhood and would be better built elsewhere. They might even latch onto social arguments, saying it shouldn’t be built because it’s not affordable enough.

Some NIMBYs don’t do themselves any favours, wearing their classism by saying they don’t want “apartment people” near them or don’t like the design of a proposed project. To this, Trauss the YIMBY says, “Just because you live nearby, nobody gives a shit what colour you think someone else’s shutters should be.”

Holleran’s book quotes a few NIMBYs that try to appear logical but end up laughable. The best example is a Berkeley homeowner who showed up at a public meeting with a zucchini to protest the property next door to her being turned into two units. “I brought a zucchini, because I love to garden. And in order to garden, you need sunlight. But this zucchini exists because I don’t have a big two-storey house next door to me right now.”

Vancouver is no stranger to these kinds of comments, with YIMBYs mocking homeowners for calling the citywide introduction of duplexes a “chainsaw massacre" and for protesting an Indigenous-led development by saying, “frankly, this is my backyard and it’s also the people of Canada’s backyard.”

Wonky, but with beer and memes

It’s no secret that YIMBYs aren’t fans of the suburbs. In addition to their belief that new homes will bring about affordability, YIMBYs also believe that density paves the way for vibrant urban life, setting them apart from homeowners who associate density with, in their own words, “crime” and “lawlessness.”

Yimbyism might be new, but the ideas they’ve adopted around urban growth have been around for a long time. Walkability, public transit, less reliance on cars, cosmopolitanism, compact communities where people can live, work and play — these stem from Jane Jacobs, who wrote the YIMBY holy text The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, whose principles played a part in inspiring an urban planning movement in the 1980s called New Urbanism. From there, planners began to include concepts like complete communities, sprawl repair and five-minute neighbourhoods in their toolkits.

The adoption of these ideas by YIMBYs led them to pick up support from some urban planners, but also politicians and environmentalists against cars and sprawl. Naturally, real estate developers were happy to have YIMBYs around as cheerleaders.

But if YIMBYs are just piggybacking off of existing ideas in planning, how did it become a new movement with a fresh face?

Communication is key, says Holleran. The politics of how cities get built are complicated and YIMBYs break it down with brevity. YIMBYs skilfully distill wonky ideas about urbanism into catchy slogans; density might sound scary to some, but who could say no to “four floors and corner stores”?

YIMBYs are great at crafting memes; who would’ve thought to mesh SpongeBob SquarePants with housing economics? It helps that NIMBY homeowners offer a lot of fodder. One meme shows someone at a public hearing saying, “You can’t permit a house to be built in that vacant lot... the birds will have no place to sing.”

But perhaps most importantly, YIMBYs show up and voice their opinions at the city meetings where decisions about new housing and neighbourhood plans are made, forums that homeowners have long enjoyed a hold over.

Oh, and there appears to be a lot of beer lubricating the movement. Sometimes it’s craft, sometimes it’s on the house. It’s guzzled around the clock: afternoon beers, meetings over beers, post-meeting beers. Author Holleran mentions conducting an interview “drinking mid-afternoon Tecate beers from the can in an otherwise empty San Francisco bar.”

Explains one YIMBY, “[I]f you don’t make your political home a social home, people will stop coming.”

Middle-class revolution

One of the most fascinating parts of the book hones in on a different kind of battle between YIMBYs and NIMBYs: both groups claim that they represent the middle class. Homeowners reference the hard work they put in to pay off their mortgages as a way to deny their own privilege. Millennial YIMBYs say that they “play by the rules,” and that they too work hard yet are paying too much for housing.

Both groups also claim to be fighting for a better future for those in worse housing need. And yet Holleran points out that YIMBYs are not the housing advocates who care about displacement, gentrification and vulnerable residents first and foremost, but solving those problems through supply. YIMBYs themselves are generally well-paid, well-educated and live comfortably. As he describes them, they’re “Young professionals who also felt squeezed by rent but not so catastrophically burdened that they are facing housing insecurity.”

This has resulted in clashes between YIMBYs, who welcome market housing, and anti-gentrification activists worried about how vulnerable residents, who are often racialized and working class, might be affected by new development. It made for a dramatic scene at the national YIMBY conference in Boston in 2018, when anti-gentrification activists crashed the final speech and took to the mic to say, “It’s hard to trust and support a movement that is not working for our communities.”

The battle over housing has also led to uncomfortable discussions about race. NIMBY homeowners tend to be white and YIMBYs often point to racist and classist histories about exclusionary zoning. But the YIMBY movement isn’t particularly diverse either, and their advocacy for new supply has put them in conflict with working-class neighbourhoods of colour.

Is it enough to say yes?

The YIMBY gospel of supply is that new homes will give everyone affordability, that even luxury condos are part of the tide that lifts all boats. Their argument, called “filtering,” is that new construction broadens choices, drives down prices, keeps rich people out of working-class areas, and lowers the cost of older units. But these housing economics have been contested by supply skepticism, arguing that new housing has the potential to actually increase demand where displacement is already a problem. Holleran does mention that existing data “shows that adding to any part of the housing market, including the higher-priced segments, eventually lowers costs,” but that this process is frustratingly slow.

If you’re a YIMBY or an anti-YIMBY looking for an answer to the supply debate in this book, you’re not going to find it. Holleran only dedicates about two pages to this topic, as he’s more interested in yimbyism as a social movement.

Having interviewed dozens of YIMBYs for the book, he credits them for bringing important civic issues to the mainstream. As urban inequality worsens, there’s high demand among citizens to untangle the causes of the housing crisis and YIMBYs were there to offer answers in colourful ways. Cities like Vancouver, states like California and even a country like New Zealand are on their way to gently densify single-family zoning, with YIMBYs lending their voices to this overdue conversation.

But the zeal of YIMBYs has earned them critics too — it’s not just about their beliefs. The Californians in particular were known for their “showboating,” “confrontational style,” a “bawdy sense of humour” and creating “unnecessary vendettas,” such as doxing opponents and publicizing the value of their homes. Other YIMBY groups starting out around the world were worried about their Californian counterparts muddying the YIMBY label and giving their advocacy a bad rep.

Holleran goes on to ask whether YIMBYs are ambitious enough. With the movement relying so heavily on the market, governments and non-market developers won’t feel the pressure to do more and get creative with public housing, land trusts and co-ops. By focusing so strongly on supply, YIMBYs are missing out on addressing how the financialization of housing is harming affordability.

Widening their scope of advocacy could rally new allies to the movement, suggests Holleran. YIMBYs say they’re advocates of everything, but perhaps they need to say yes to even more. ![]()

Read more: Books, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: