The old phrase about wearing your heart on your sleeve got it wrong.

Short or long, you can’t tell much from a person’s sleeve. Hats on the other hand, err head, I mean, can instantly relay reams of information about a person. Who they are, who they would like to be and what they want to say to the world.

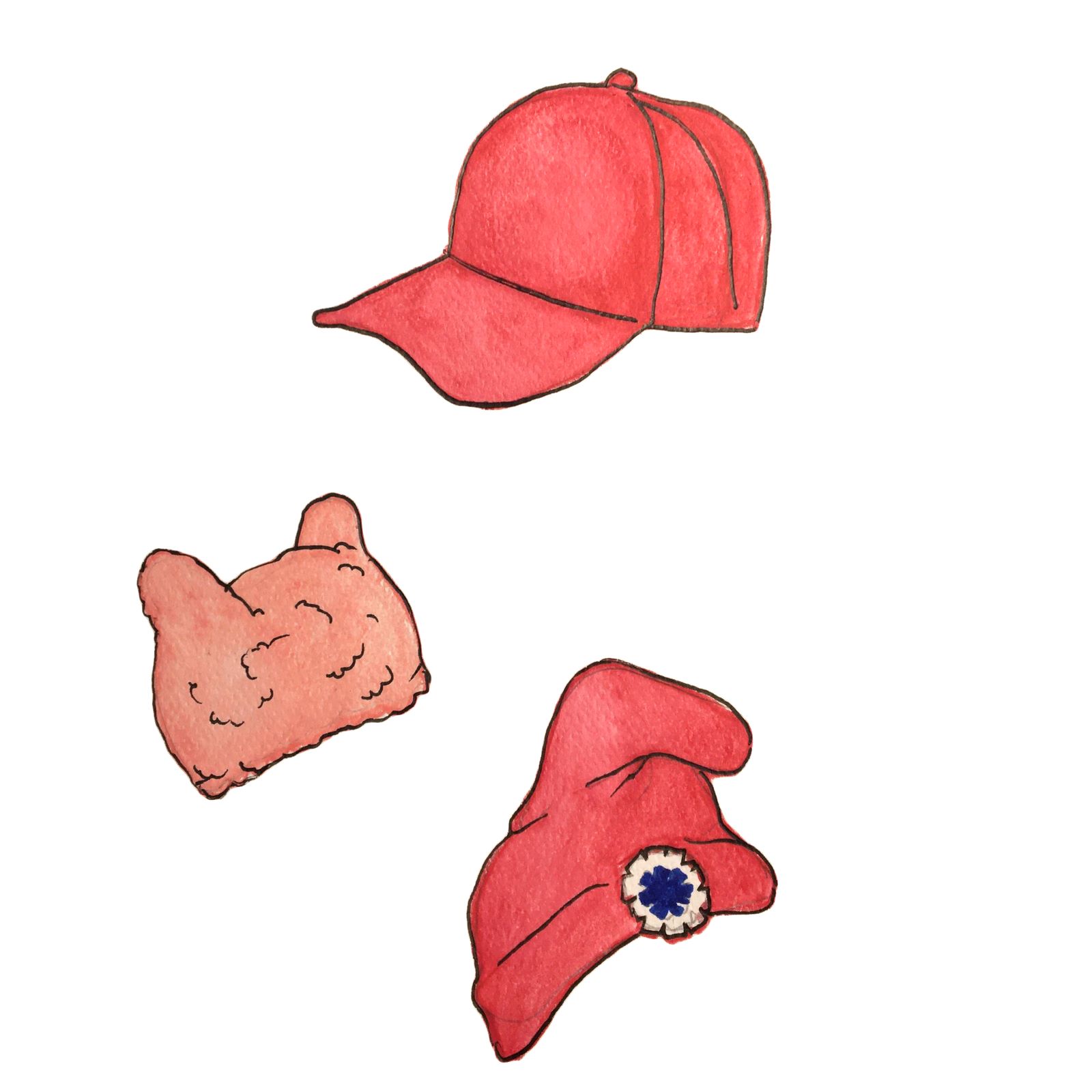

Backwards baseball cap-wearing bros, a young woman sporting a bolero so large it could wipe out a small town, or a dude in a black fedora and a white tie with piano-keyboard pattern. Jeez, there are a lot of really irritating hats out there. But when I see someone in a red hat, every nerve ending leaps to attention, as if to sound the alarm that a potential wingnut is near.

Folks are much more likely to wear their hearts, as well as their political ideology, cultural affiliations and socioeconomic positions on top of their heads.

Think of famous leaders. What comes immediately to mind? Hats! The beret of Che Guevara or the Black Panthers, the jaunty khaki cap of Fidel Castro. Want to unite folks under a common banner? Give them cool hats.

But dig a little deeper and all kinds of arcana related to the stuff people wear on their heads pops up. The politics of headgear have a long and extremely kooky history. One style, in particular, has enjoyed an enduring run.

In the heady days of revolutionary France, the sans-culottes dressed in long trousers (eschewing the silky drawers of the elite) and wore nifty beanies. The French world-changers derived their favoured caps from the formerly enslaved people of Ancient Rome who wore similar headgear inspired by Libertas, the God of Freedom. The tight-fitting style was topped with a floppy dome. Think Papa Smurf with an agenda.

Phrygian hats have a long and well-documented history, stretching back to the fourth century. Over the millennia, the little red cap made its way through different cultures from the Thracians to the Romans, until they were rebranded as the bonnets rouges by the French revolutionaries. The sans-culottes announced their intentions to overthrow the old order by taking off their pants and slapping on some hats.

It all went so well — for a while. Like most revolutions, what started with grand statements about freedom and equality soon went straight to hell. When the guillotine got to chopping, folks who wished to blend in with the new establishment took to wearing the hats as a form of camouflage. Ultimately, the fashion as well as the political influence of the sans-culottes proved so great that other folk in Europe adopted the style, thus paving the way for French fashion dominance forevermore. The idea also made its way across the ocean, with the American revolutionaries adopting similar hats and ideology.

Right or left or somewhere betwixt, the little red hat has proven a tenacious symbol for all sides of the political spectrum. One reason that hats work so well in creating a communal group think is that they often seem to short-circuit the brain. Adopt a hat and you take on its creed. When you witness a sea of people all wearing the same hat, you know they’ve consigned the thinking stuff to someone else, usually the person who told them to put it on in the first place.

It works equally well if you’re a French revolutionary, an American Trumpite or a Russian school kid.

This form of identity building and allegiance goes both ways — from the top to the bottom and vice versa. When leaders wish to appear more akin to the common people, they will plop on a hat and proclaim, “I’m one of you, guys! Just look at my hat!” Think Lenin donning the flat cap of the workers to signal a profound shift in his political direction.

More recently, and ridiculously, think of the 10-gallon Stetson riding high on Alberta’s recently resigned leader Jason Kenney. If the very big hat was supposed to radiate masculine prowess and giant penis power, it didn’t quite achieve the intended transformation. Maybe thus crowned, Kenney felt bigger and more manly. Unfortunately, his magic hat didn’t prevent him from losing the support of his party. Picture the scene where little Kenney takes off his giant hat and puts it high on a back shelf, pausing briefly, while a slow tear makes its halting way down his cheek.

Then there’s the Make America Great Again, or MAGA, baseball cap. Its connotations of all-American stuff like sports and trucker hats transformed Donald J. Trump, a scion of East Coast money and privilege, into a down-home everyman. It worked like a charm. The red hat camouflage once embraced by the French aristocracy to avoid Madame Guillotine and blend in with the common people still works for those wishing to pretend to be something else.

As symbols, hats are a very efficient form of political dress. For one thing, they’re up high where everyone can see them. From this position, they can broadcast the notions of the hat wearer without them having to say a single thing. In the case of the incoherent, the deeply confused or the downright addled, this might be a good thing.

Hats have long been a form of social semaphore. Once upon a time, your hat determined what you did for a living, how much money you had and ultimately your place in the world. If you wore a navy watch cap, you better be a sailor or a longshoreman and not some hipster from Hoboken.

Speaking of which, allow me an aside for a moment on the odd fixation on wearing a beanie as high as possible on your head, acres above the ears, scraping the very firmament of the sky. It is, perhaps, the most irritating hat trend of all time. Comedian Brian Park’s TikTok provides a good introduction to this epidemic of frozen-eared insanity Hey you, precious hipster with a beanie perched at the very apex of your skull, your mother will be very annoyed when you get frostbite and your ears turn black and fall off. Okay, rant over.

In her book Fashion and Its Social Agendas: Class, Gender and Identity in Clothing, author Diana Krane explains the role once occupied by headwear. “Until the 1960s, a man’s hat, as the most immediately visible part of his costume, was a major signal of social identity and social class. Specific styles of hats were associated with different class strata. In the late 20th century, men’s hats have become a relic of a class society based on face-to-face relationships in public spaces that has largely disappeared.”

Except that the class issue has had a resurgence of sorts and hats are at the forefront of the divisiveness.

This is the case even with pussyhats, those damn pink-eared knit creations popularized during the 2017 Women’s March. One would think that millions of pissed-off angry women would want something that made their feelings a little clearer than a fuzzy pink hat with two perky little ears. Even if your mouth is yelling furious protest statements, your hat is saying “I’m so cute!!!”

Personally, I think we women might want to rethink our radical headgear of choice going forward. A nice balaclava might work, or even better, an anatomically correct vagina hat, like the one modelled by Canadian musician Peaches. A bit terrifying, but hey, it makes a statement.

To return once more to the original meaning of the Phrygian hats, the humble cap once stood in opposition to more elevated and wealthy headgear, like crowns for example. But red hats have come to mean different things of late, as the Trumpian hordes have demonstrated. The crimson cap represented the concept of a republican government. And it means “republic” in the original sense of the word: government by the people for the people. That freedom hats have been purloined to mean something quite different in recent years is pretty depressing. But even the word “freedom” has come to mean very different things to very different people.

That’s the thing about symbols. Their meaning can shift depending upon who is in control of them. The bonnets rouges, initially equated with liberty and justice, became a form of control and propaganda, as people were forced to wear them as a sign of fealty to the revolutionary cause. Hats on or heads off, as it were. Prior to his execution, King Louis XVI was forced to wear a red cap and by 1793, French politicians were obligated to wear them by law.

Hats can hide a multitude of sins — bad hair, no hair, a giant forehead — but they can also reveal far more. If wearing an ideology atop one’s head means that you acquiesce to a certain way of thinking, it’s not as easy as simply taking off one hat and putting on another. Or is it?

As summer lurches into sight and even more hats come out — bucket, straw, straw in a bucket, Beanie Babies, Panama — perhaps it is time to cast off the old hat and embrace the new. Off with the trucker caps and on with a different breed of chapeau, a green hemp-derived creation, sustainable, locally made, as natural as a crown of wildflowers. Like wearing a hay bale on your head. Change your hat and change your mind. ![]()

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: