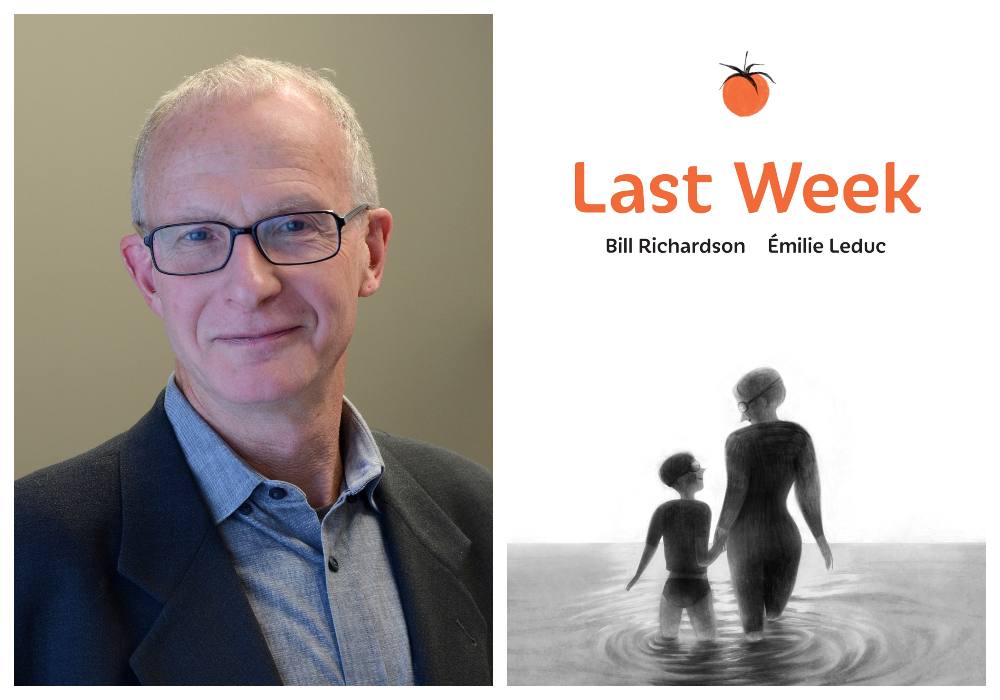

The subject of death is not an easy thing for anyone to contemplate, much less through the eyes of a child. This inherent complexity is what makes Bill Richardson’s new book Last Week, published by Groundwood Books, such a remarkable work. In an elegant dance of image and prose, the story details the final week of a child’s beloved grandmother before she takes her exit with medical assistance in dying, commonly known as MAID.

Flippa has always lived her life exactly as she wanted, whether that includes donning a wetsuit, goggles and flippers for her daily swim in the ocean, or genial arguments with the local greengrocer. As the family comes together, every second is accounted for by her grandchild, who tallies up the time left as her grandmother’s final day approaches.

As much a meditation on the beauty of living as it is a clear-eyed look at a final rite of passage, Last Week is filled with humour, love and wonderfully nuanced illustrations from artist Émilie Leduc.

Based in Vancouver, the inimitable Bill Richardson is a writer and former radio and television presenter. In addition to the Stephen Leacock Medal for Humour, his work has won multiple awards including the Silver Birch Award, a BC Book Award and a Manitoba Book Award.

On the eve of Last Week's release on April 1, The Tyee posed the author a few questions about his work. This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: One of the things that I liked most about this story is its calmness. It doesn’t pretend that death isn’t sad, but also doesn’t shy away from the idea that it can also be liberating.

Bill Richardson: Thanks for that. I'm very glad of the observation. The story is short and simple. Within it, as with all stories, are complications. One is that, although the child inhabits a "traditional" family — a mom and a dad — the mother is missing for most of the story. In this case, it's because the mother works, she's a doctor, she's coming when her schedule allows. Also, the grandmother, Flippa, who's choosing to die, is the child's paternal grandmother. Of course, her son — the child's father — is there.

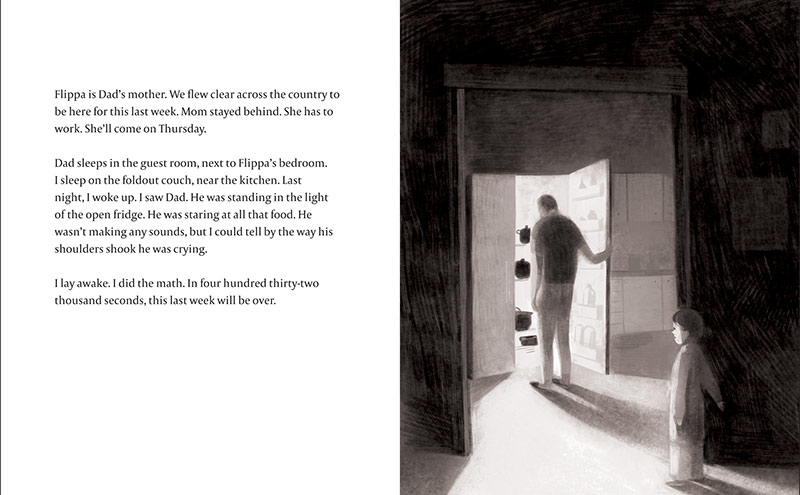

I wanted the child to have the experience of seeing their own parent come a bit unmoored. I didn't want to make a big deal of it, narratively; just wanted to suggest that there comes a moment in any child's life when he/she/they understands that their parents have their own vulnerabilities; that there are times when they, the children, young as they are, can step up to the plate. It's part of maturation. The child intuits that there are degrees of magnitude, understands that their father is deeply affected by this loss, this impending loss — he's the one closest to it. The calmness is a kind of support mechanism: his grief takes precedence.

This is the first time I've written a book for kids where I was deliberate in not being specific about a gender for whoever the central child or child surrogate is, in the instance of animal stories. I wasn't interested in making a statement about gender identity, there's enough going on here. It just didn't seem important to me. Also, I wanted to give illustrator Émilie Leduc interpretive leeway.

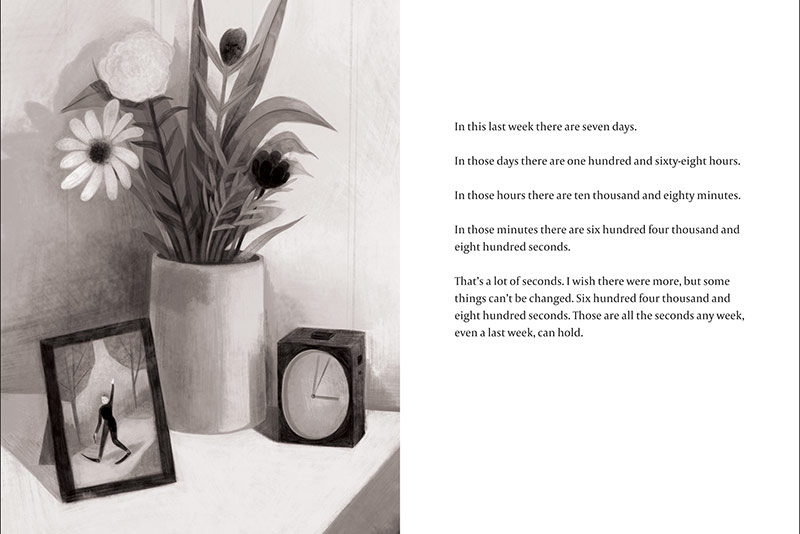

Where did the idea of a countdown, as a framing device, arrive from?

This connects to calmness, see above. I was struck by something some friends told me about their daughter, a gifted young woman, beautiful, talented in many ways, and a slave to perfection. At math, she was especially adept, and she told her parents once that she found numbers made her feel calm, centred, reassured. I just loved that, especially because I don't understand it, not at any deep level.

I'm essentially innumerate, didn't go beyond Grade 11 math, and I’m not even sure I know the times tables at this point. But I could imagine well enough how something that would require a particular focus… that you could turn around and around in your head until you found a solution that was unimpeachable, unequivocal, would be reassuring. So, that's the source of the countdown.

Do you think the idea of knowing and waiting for someone to die changes how we process the experience?

Absolutely. At 66, I’m properly of an age to die and no one can say too soon. I'm a gay man who lived through the AIDS pandemic. I saw a lot of death quite early on. I didn't become inured or habituated, but I did — as did anyone else of my generation — have cause to pause and reflect.

Then AIDS settled down, became manageable, and there was a long period of merely intermittent mortality, the usual stuff. The occasional suicide, the out-of-the-blue accident, the now-and-again cancer. But now it's ramping up again, in the more natural way of things. The elephant has come to dwell among us in the room and candour, at least, is easier now. We can joke more readily about the wisdom of buying green bananas, and so on. There's nothing new about this — it's mud-common.

Dr. Stefanie Green’s afterword in the book is very practical, clear and matter-of-fact, which I really appreciated, and it also gives a lot of room for kids to have the feelings they have, without worrying whether they’re not the right feelings or reactions. Did you draw on your own experiences of death when you were writing?

Dr. Green, a MAID pioneer, has just published a memoir called This Is Assisted Dying. I was so glad she agreed to write that postscript. I met her in 2016, when she was the attending physician at the assisted death of my partner Bill Pechet's mother Judy. Judy was a remarkable woman. She was so smart and funny and warm and gregarious, hugely welcoming. I adored her. Anyway, her body was failing, she was in her 90s, she didn't want to hang around, and the "right-to-die" legislation had been introduced and she found a way to take advantage of it.

It wasn't straightforward, but she was determined. She made it happen. For a few days before she died, her family and friends gathered. We all sat around in her home in Victoria and talked and laughed and ate a hell of a lot. She loved to cook and loved to eat and loved to feed people: she was the quintessential Jewish matriarch. What impressed me, and what I remembered three years later when I wrote the text for the book, was how determined and unsentimental she was. She was a woman who had always, I think, prized her agency, and who was using it to make a graceful exit on her own terms.

This was very much in my thoughts as I wrote the few words that comprise Last Week. And I remembered Stefanie — how reassuring she was, how calm (that word again), how supportive, how matter-of-fact. Of course, it was an emotional time, but it wasn't lachrymose. Judy drove that, and Stefanie supported it. It was, in the end, a reasoned, practical decision. It was a strange experience to mourn in advance, to know there was a date, an appointment. But it wasn't uncomfortable or strained; merely novel.

MAID legislation came into being in 2016. Did you know much about it before you started writing? Do you think people are now more comfortable with the idea of medical assistance in dying?

I didn't know much about it, beyond being aware that there were clinics here and there, in Switzerland, etc., that made "death with dignity" possible, and I was aware of the Hemlock Society. But I've always, for as long as I've had cause to think about it, supported the idea that we should be able to choose the time of our leaving. This is a book for young people, it's centred on a very specific situation, it doesn't get into the nuanced, complex issues around MAID. That's not its point.

As for being comfortable with the discussion of MAID, well, when anyone asks me about this book and I describe its reasons, they know someone, or know of someone, who has benefited — I used the word advisedly — from a medically assisted death. It's become absolutely commonplace.

Within my own extended family there have been two assisted deaths in the last couple of months. The pandemic has brought about its own imperatives and shaped our discussions of dying, but I fully expect — and appreciate that I say this as a layperson who has no good reason to offer an informed opinion — that MAID will become more and more an exit strategy, for all kinds of people, for all kinds of reasons.

My own feelings about this choice are not uncluttered or unalloyed. I haven't reached a clear determination for myself about whether or not, should circumstances allow, I'd choose MAID. I have great respect for people who would rather tough it out, let nature take its course, and so on. But I'm powerfully glad that MAID is there, as an option for many; even if it's not, to my thinking, sufficiently open-ended.

In the midst of the pandemic, when a great many people are having to navigate the reality of death, what would you like Last Week to offer?

Well. Good question. Didacticism in children's literature makes me uneasy. It can be so, well didactic. I mean patronizing. Paternalistic. Narrowing. Stefanie's excellent postscript to the book answers the need to speak specifically to the question of what MAID is all about. In the story proper, there are a few lines about what happens, medically, but mostly, it's a book, I hope, about love and loss and transcendence. It's a book about life and the necessity of leaving life. It's a book about knowing a miracle when it comes along. It's a book about family. MAID is not the prime motivator, MAID is just the guy who pulls the curtain when the scene is done.

So, I hope that it offers, in a modest way, as it's the work of a writer with modest skills, a chance to sit quietly with those ideas which, while modestly expressed, are conundrums that we grapple with from an early age, all through our lives, right to the end. ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: