There was an era when we believed our shining Rocky Mountain glaciers were as obdurate and eternal as the rocky beds in which they reclined. Eternal seems a very Victorian notion about mountains, part of the “golden age” of Canadian mountaineering, when most of Canada’s major peaks were first ascended. It was a delusion I succumbed to for many years concerning Abbot Pass, the glaciated canyon between Mount Victoria and Mount Lefroy, which rise high between Lake O’Hara in Yoho National Park and Lake Louise in Banff National Park. For over a century Abbot Pass has been the main access route to ascend those peaks.

I had the same expectation about Abbot Pass Hut, a solid stone building on the pass summit constructed by the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Swiss mountain guides in 1922 for the use of their mountaineering clients.

At an elevation of 2,925 metres, it was for many years the highest habitable structure in Canada, since edged out by the Neil Colgan Hut on the Fay Glacier, at 2,957 metres. Abbot Pass Hut was officially acquired by the Dominion Parks Branch in 1968, then assigned to the control of the Alpine Club of Canada in 1985. In 1992, Parks Canada designated the so-called Abbot Pass Refuge Cabin and its surroundings as a national historic site. But this year, Parks Canada did not announce a centennial celebration for the beloved refuge. Instead, the hut will be removed this summer. Like the Lower Victoria Glacier that it overlooks, the hut is yet another casualty of climate change and glacial recession.

According to an old colleague of mine, Robert Sanford, who is a Global Water Futures fellow at the Institute for Water, Environment and Health, some 300 glaciers have disappeared in the Rocky Mountain national parks between 1920 and 2005. Things are getting worse. In the extreme summer heat of 2021, the toe of the Peyto Glacier retreated some 200 metres. This is “10 times faster than the last half century of retreat,” according to hydrologist John Pomeroy of Global Water Futures.

The Abbot Pass Hut’s foundations are sitting on the headwall of the Lower Victoria Glacier. The lip of the ice at one time nearly reached the hut’s east wall. Now the glacier’s edge lies 50 metres downslope. The builders and stone masons in 1922 may not have realized that the col of compacted scree and fallen rock was stabilized over time by snow, ice and permafrost. This matrix is melting and eroding. According to Parks Canada, in 2021, “approximately 114 cubic metres of material fell from the slopes under the hut.”

This undermining of the hut foundations threatens to topple the building. Since 2017, Parks Canada has spent some $600,000 on geotechnical studies and the installation of rock anchors to try and save the hut. The anchors have been to no avail. The work was also interrupted by bad weather, lifting limitations of supply helicopters and pandemic health mandates; the hut is now too dangerous to use.

Zac Robinson, vice president for mountain culture with the Alpine Club, describes the news as “absolutely devastating for our members and for the history of mountaineering in the Rockies.”

The men who built the hut — without the backing of their employer Canadian Pacific Railway — were two Swiss guides named Edward Feuz Jr. and Rudolf Aemmer who, as Robinson says, “were homesick for their Swiss mountain culture.” The duo hired local outfitters to haul building materials up the glacier with horses and mules as far as they could go. When the ice got too steep for the equines, the men used sleds and winches to move the material up to the summit.

Although it looked more Swiss Alps than Rocky Mountains, the little cabin, made of limestone quarried on site, had the organic presence of a temple, or a toll booth between heaven and Earth that had risen magically out of the rocky saddle of the Great Divide.

“Where else can you climb two 11,000-foot glaciated peaks in one short trip, and have such a wonderful place to stay between climbs?” asks Robinson.

“It was such a special place. There was always a group of people staying there, often a lot of strangers. So after the climbing was over for the day, the cozy little hut made for such warm camaraderie and good cheer. The place was just made for storytelling.”

I have traversed the Abbot Pass from Lake O’Hara in Yoho Park and Lake Louise in Banff National Park many times, starting in 1962 when I took a summer job at Lake O’Hara Lodge and began climbing the local peaks. Patrolling the pass was part of my duties in 1966 as an assistant park warden at Lake O’Hara.

As a warden, I often overnighted at the hut, sometimes accompanied by my immediate supervisor, mountain guide Bernie Schiesser. The hut will sleep about 20 people, and the attic contained dozens of red Hudson Bay point blankets that had been packed up from Lake Louise by the CPR’s Swiss mountain guides back in the 1920s. These made for cozy, if not dusty bedrolls on stormy nights. We kept them draped over a wire clothesline out of reach of the pack rats that sometimes haunted the joint.

We were responsible for maintaining the hut in those days, and every week found one of us (usually yours truly) backpacking supplies of firewood, kerosene, shingles and hardware from Lake O’Hara at 2,020 metres up to the 2,925-metre pass. The trek involved a gruelling slog up 457 metres of loose scree to reach the hut.

In those days the heavy snowfalls of winter refreshed the world-famous view of the Lefroy and Victoria glaciers, that much diminished selfie-scape that is jpeg-ed a thousand times a day every summer from Chateau Lake Louise. Snow often packed the crevasses of the Lower Victoria Glacier in Abbot Pass with solid bridges that lasted into late summer. As I recall, it took from two to three hours to reach the hut if conditions were favourable.

It is an easy hike of less than six kilometres from Lake Louise to the Plain of Six Glaciers Tea House. But from there the trail ends and the route up to the hut threads through the notorious “Death Trap” canyon of the lower glacier.

This spot is particularly prone to avalanches and ice falls from the upper glacier on Mount Victoria. It was always an eerie place for mountaineers to transit; nowadays the Death Trap is impassable. The worst climbing accident in the history of the pass occurred in 1954, when four climbers fell near the summit ridge of Victoria and rolled in a snarl of ropes and crampons down the ice, then plummeted over a glaciated cliff to smash into this forbidding redoubt.

Even back then, the Abbot Pass route should never have been attempted by people who lacked crevasse rescue training and equipment. But as a 17-year-old ingénue at Lake O’Hara Lodge, I thought nothing of trotting solo over the pass and beetling down the other side among the crevasses on a day off to buy pipe tobacco at the Chateau Lake Louise, then catching the late bus back to O’Hara. I tremble at such blissful ignorance now, even as I long for the speed and stamina that made it possible.

I once encountered a pilgrim of sorts who had made the journey from Moraine Lake to Lake O’Hara via the Opabin Glacier clad in a saffron-coloured robe and straw hat. His feet looked battered and slightly frostbitten. He did point out to me that his sandals had rubber soles made from old car tires which gripped well on ice. When he left me, he was headed for Abbot Pass, and to this day I don’t know if he made it back.

Note to Tourists: Abbot Hut is not a tea house! Mountain guide Peter Fuhrmann was in the hut one evening, he told me, when a frost-rimmed apparition dressed in a dark business suit rapped on the door to enquire, “I say, is it too late to get a cup of tea in this place?”

On another occasion, returning on a climb of Mount Victoria, Fuhrmann noticed some odd tracks in the snow of the Death Trap. At the Plain of Six Glaciers Tea House, he discovered who’d made them — two 14-year-old girls “just dressed in shorts and tennis shoes, and little tops.”

The girls said, “Where did you come from today?”

“We climbed the north peak of Victoria,” said Peter. “How about you?”

“Oh we went up to the other tea house [Abbot Hut] and then came back here,” they replied. “We had tea up there and they didn’t even charge us for it.”

In 1999, I was planning a nostalgic trip through the pass and a sentimental climb of Mount Victoria with two old ropemates. I had not climbed in the area for 20 some years. I checked on the route with Fuhrmann and with a former colleague, Tim Auger, who was then in charge of the public safety team for Banff National Park. The pass, I learned, had been trashed by climate change. “Nobody uses the old route anymore,” Auger warned me. “It’s nothing but holes and seracs.”

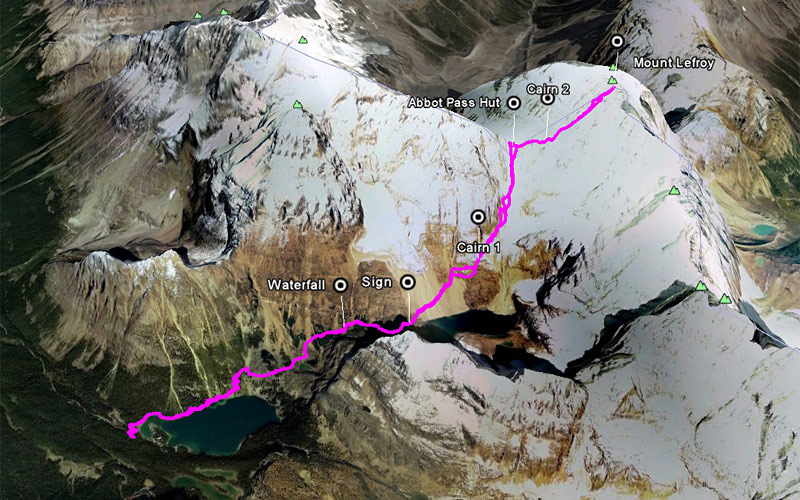

“It’s been a no-go zone for at least five years,” Fuhrmann explained at the time. He told me that instead of one bergschrund — the name for mega crevasses that typically form near the top of a glacier — there were now about 20. Fuhrmann has instead revived the old Swiss Guide’s route that follows a yellow rock band up along the west side of Mount Lefroy to reach the pass.

“Follow the yellow band,” he suggested, cheerfully, as if it was some kind of yellow brick road.

I came away shocked and amazed at how the ice, which had carried generations of mountaineers to the summits, had shrunk and crumbled away in my own brief lifetime to a shadow of its former grandeur.

Abbot’s Pass is a storied landscape and the abode of spirits, of belly laughs, fabulous adventure and terrible tragedy.

The pass is named for an American, Philip Stanley Abbot, who perished in the second attempt to climb Mount Lefroy in 1896. The first sortie, led by Walter Wilcox in 1894, also ended with an accident, and a rescue. A young Yale student named Lewis Frissell fell off a ledge and was struck by a dislodged boulder, which dislocated his hip. A fellow climber hurried down to Lake Louise where he recruited four workers at a tourist chalet to come help. The party included two members of the Stoney Nakoda Nation, William Twin and Tom Chinquay, who upon reaching Frissell, carried him down the mountain in a sling made of canvas and wooden poles.

“The labour of carrying Frissell over the glacier and moraine was enormous,” one member of the climbing party recalled, yet Chinquay “never murmured though his moccasins were in rags.”

Mountain humour can vary from cosmically grim to downright scatological. The original outhouse at the hut, for example, was a plywood wind tunnel whose bottom exited on the scree slope on the south side of the building. There were many yarns about the wind blasting back up the outhouse hole to plaster contributions back onto the bums of the contributors. I even wrote a folk song once to celebrate the ancient crapper. Part of it went:

And mountaineers will tell you and surveyors agree

The hut sits in Alberta so fair and the shithouse in B.C.

The newer, very deluxe outhouse, a kind of throne-room-of-the-Gods built just above the hut, had its own fabled history, since if you happened to be present when the maintenance helicopter arrived, you were bound by hut rules to help handle full 50-gallon barrels of ordure into the cargo net to be flown out for disposal.

Although the old plywood wind tunnel was burned long ago, Zac Robinson said the Alpine Club hopes to preserve some worthy cultural artifacts from the site, including the windows, and hopefully use parts of the hut in the construction of a shelter in another location, but replacing the hut in situ seems unlikely.

Not everybody is convinced that the hut’s days are over, however. A number of engineers have come forward with proposals to protect it. Fuhrmann, who for 13 years served as a regional draftsman for the federal Department of Public Works, has helped design bridges, tunnels, river diversions and highway alignments. He is convinced the hut can be saved. He says he knows an engineer who can do the job and who can find a team of workers with the skills to make it happen. As this goes to publication, he hopes to present his idea to the Alpine Club for an 11th-hour rescue of the famous shelter.

Describing the hut in my book Switchbacks, I wrote “the first time I saw it was the first time I really understood the love affair between men and mountains. Abbot’s Hut — a place made to be haunted by their shades. At night, the beacon of a candle flame in its window was like a lighthouse in the clouds.”

I am one of those who have seen nearly every home they ever lived in fall to the wrecker’s ball, so memory is constantly challenged by a reality that has erased the objective touchstones of my past. I am not alone in this modern form of spatial amnesia.

Still, losing a place like Abbot Pass Hut, which was a focal point for so many lovers of mountain wilderness, is somehow worse.

However this issue is decided, one thing remains clear to me. When the sanctuaries and temples of a culture are gone, the spirits of the past have no place to gather and speak across the ages to the transient souls of today.

And we are all lessened, as humans, by that kind of loss. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: