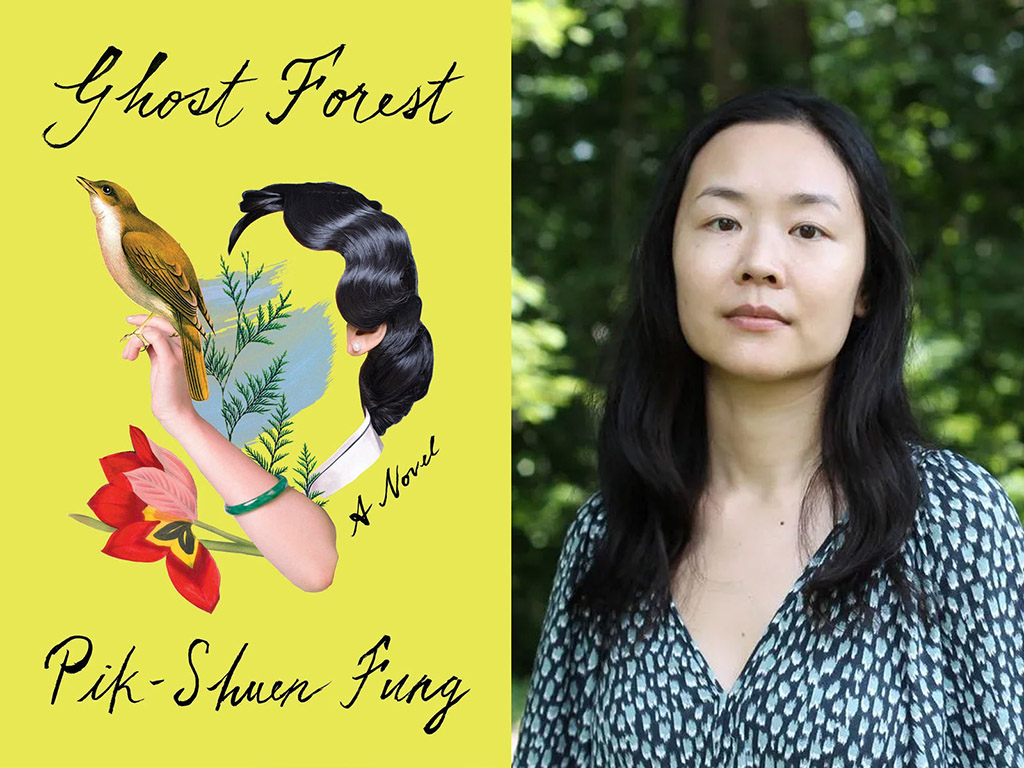

Ghost Forest

By Pik-Shuen Fung

Strange Light (2021)

Astronaut dad only visits once a year. He lives in Hong Kong, while his wife and daughters are in Vancouver.

The annual visits, always at Lunar New Year, are stressful events for the family at the centre of Ghost Forest, the debut novel by Pik-Shuen Fung.

“For two weeks, everyone tiptoed up and down the stairs, and watched television with the volume on low,” writes the unnamed narrator, the older of the family’s two sisters.

“[W]e were quiet because my dad was jetlagged, and whenever he couldn’t sleep, he got angry, his eyes reddening behind his wire-rimmed glasses. He never raised his voice though. His anger was the cold clenched kind that left the room in silence... I think of counting down the days until our house could be itself again.”

The “astronaut” moniker is apt for this particular spaced-out dad.

Hong Kong media came up with the term “astronaut family” to describe an arrangement that took flight in the 1980s, adopted by upwardly mobile families. Dad kept his job in one place, while mom and the kids settled in some western country with an attractive education system — the number one reason, according to research on these family units, for the arrangement.

This privilege makes it different from other families separated by distance, such as the Filipino and Latino parents welcomed by countries like Canada to fill labour gaps. As Taiwan, Korea and China grew their economies, they too grew their share of astronaut dads. The practice continues today.

Growing up in Vancouver, I had dozens of friends and family in these arrangements. I remember visiting friends who were children of astronauts and watching all activity in the household freeze when appa called from Korea.

As for the wives of astronauts, they ferried kids to extracurriculars, researched universities, volunteered at church and took up humble jobs at the local bakery to fill the time. Come Lunar New Year, just like in Ghost Forest, Vancouver’s population would swell with vacationing dads.

But the privileges that come with this arrangement also comes with strains. How does it affect relationships?

In Ghost Forest, the narrator has no joyous reunions when she meets up with dad. Instead, he says things like, “You’d look better if your face were thinner.” And when the narrator surprises him with a trip to a gallery where one of her paintings is displayed, he says, “I think there is something wrong with you that you’re making art like this.”

The tone of the relationship carries on into adulthood. The narrator is working in London when she receives a call from mom. Dad has liver disease, but don’t worry about him, she says, because “worrying is bad for your spleen.”

Whether it’s due to the physical distance or cultural differences at play, much is left unsaid. Death isn’t talked about. Illness is downplayed. “You’ve got to tell him happy things,” an aunt instructs the narrator. Even when picking out a movie for dad to watch at the hospital, mom says it has to be a happy one.

Is this avoidance? Or a kind of care and communication the narrator isn’t used to? Whatever the case, she’s determined to tell her father she loves him before the end. She’s never done it before. Neither have her peers from similar families. And when she talks to her mom about it, her mom hints she’s never heard the words from her own husband.

Fung’s slim but intimate novel simmers with the struggles of what to say or what not to say, as well as questions about what someone is really saying behind their words.

Most of the scenes only last a page, but they’re vivid vignettes of the astronaut life. During a family visit to Hong Kong, dad shows his daughters the nice apartment with the waterfront view he lives in without them, then goes to watch TV. The daughters pull out their laptops to message their friends back in Canada.

We get to know the family well, even as they realize how little they know each other. Intentional conversations are hard for them, yet intimacy arrives out of the blue when dad and mom share surprising details about their childhoods.

There are snapshots too of the family adjusting to life in Vancouver, likely drawn from Fung’s own experience as a member of an astronaut family. Grandparents, used to urban life, complain how quiet the streets got at 7 p.m., with “no one, not even a ghost” around. Mom chats with a friend at a Zellers in Cantonese, only for a white stranger to march over and say, “You Chinese are too loud!” And during a trip to grab a bite at the food court of Aberdeen, the largest of the local Chinese malls, mom runs into a friend. “You immigrated?” they both exclaim in surprise.

This is an important novel that looks into a kind of transnational Canadian family that has proliferated over the years. You might’ve read articles that ask whether these families are freeloaders or tax cheats, rather than examine the big and the small of the issue: how Canada has been shaped into a receptive environment for astronauts to land, and how these families are doing.

Ghost Forest offers a rare, melancholic portrait of the latter.

Near the end of the novel, the narrator asks mom what it was like to give birth to her sister in a foreign country while her husband was overseas. Her baby sister’s platelet count was low. She was given painful infusions. She wasn’t expected to live.

Dad called every day, but news was scant from the hospital. And so, he got mad. The baby’s condition stabilized, but her mother was still on edge over the years. And when dad saw her upset, he got upset at her. She never told him how she felt.

“We spend so little time together,” she explains. “Why not spend it happily?” ![]()

Read more: Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: