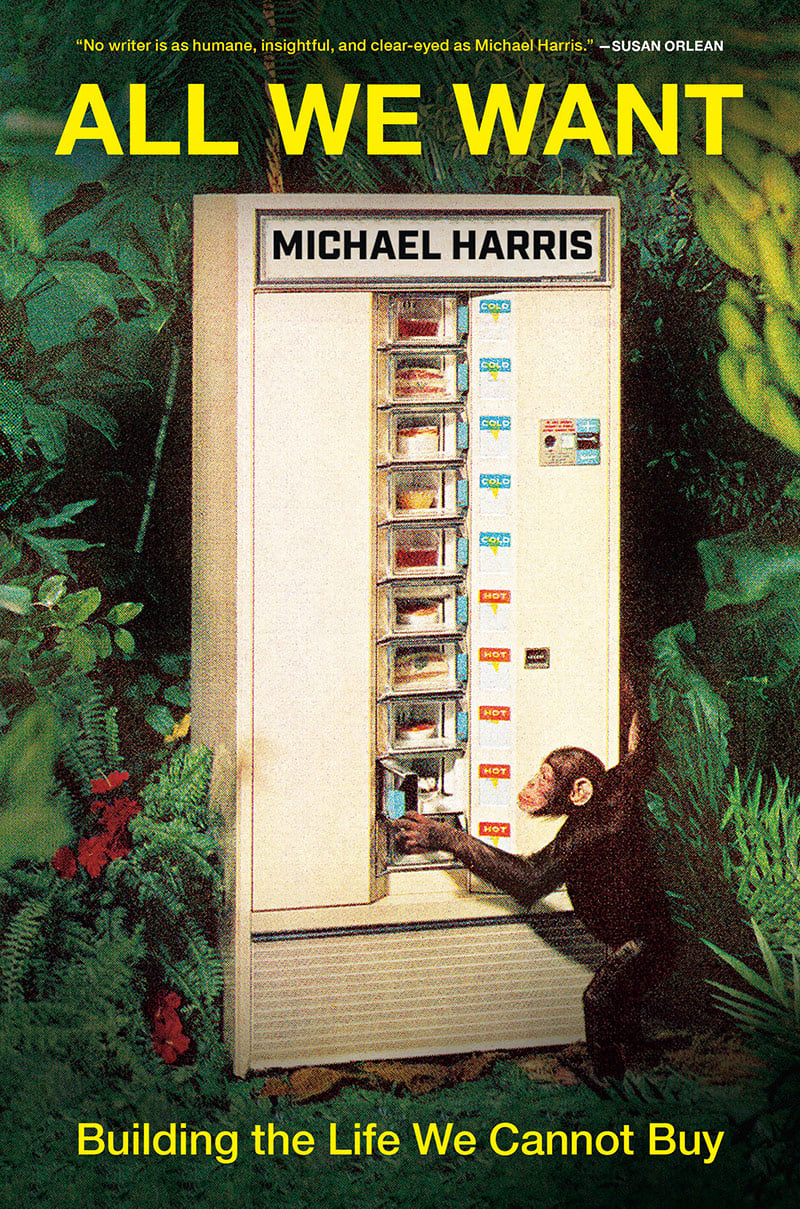

On the face of it, Michael Harris’s new book, All We Want: Building the Life We Cannot Buy, is about consumerism, climate change and the big old mess that we’re in. But it’s actually something deeper and more introspective than it first appears. At its heart is a story about the way the world works. Or at least, the way we think it works.

On the phone from his home in Vancouver, Harris explains that he wanted to achieve something more poetic than the usual disaster scenarios. “We can’t see beyond consumer culture,” he says, even though it’s an anomalous, almost ahistorical way of living.

For long periods of human existence, little to no growth was the norm. But the dominant narrative for the past century, Harris says, has been one of ever-increasing growth, aided, abetted and stoked to masturbatory levels by corporations, governments, lobbyists and advertisers.

It’s also a lie.

One of the first people to discover a slicker way to sell stuff to the masses was Edward Bernays. The nephew of Sigmund Freud, Bernays was born in Austria and raised in New York. After a stint as a propagandist for U.S. president Woodrow Wilson during the First World War, Bernays decided to apply what he learned to peacetime society, coining the term “public relations.”

Bernays’ talent lay in getting people to equate products with ideology. One of his first triumphs was to link cigarettes with female emancipation. As Harris recounts in his book, in 1929 Bernays used the name of his female secretary to invite a bunch of debutantes to participate in a “smoke-in” on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue.

Several fashionable young women showed and smoked up a storm for newspaper cameras. The event was a sensation, and within weeks women across the country were brandishing Lucky Strike cigarettes, dubbed “torches of freedom,” blackening their lungs in the name of liberation.

The story is indicative of what canny marketing can do. Although presented as a spontaneous happening, the event was carefully controlled and shaped from the outset. The women chosen were well-connected and attractive, but “not model-y,” according to the orchestrator Bernays — the idea being that they would appeal more to ordinary people.

And so the shift from a needs-based culture to a desire-based one took off like a rocket to Mars. What Harris calls “a calculus of desire was born,” and it became the dominant story of the age. It still powers along today, becoming more sophisticated as technology has advanced.

Bernays’ ideas have since been honed to razor’s edge by firms like Google, Apple and Facebook, not only to sell products but, as Harris argues, to “give rise to our being, the oxygen supporting every Brand Called You.”

And it all worked pretty well, until the reality of endless growth on a finite planet pooped on the party.

The idea that consumerism must end before it ends us has been the subject of several books this year, including J.B. MacKinnon’s The Day the World Stops Shopping and Arno Kopecky’s The Environmentalist’s Dilemma. Although each book is quite different, they form a curious triumvirate, overlapping and dovetailing in fascinating ways.

One commonality they share is the size and scale of the problems we face. As MacKinnon made explicit in The Day the World Stops Shopping, consumer desire has outstripped all reason and rationality, becoming a metastatic growth, cancerous and devouring. Harris reiterates this idea in his book: “We love the consumer story all the more as it grows monstrous and absurd.”

But the authors all collectively agree we’ve reached the endpoint of this particular narrative. “The harsh reality is that not changing is no longer an option,” says Harris. “Our entire civilization is dependent on a stable climate.”

And if the current global pandemic was merely a warm-up act for more seismic change yet to come, there is a strange bright side. Harris argues the pandemic offered an existence proof, meaning that when widescale change is necessary it can happen.

But, as with most things with humanity, it’s reactive. Jolting people from the deeply ingrained and carefully stoked habits of runaway consumption is likely going to require more widespread calamity, chaos and suffering before things truly shift.

So, what’s the solution to the ever more insidious consumer culture and the possible end of human civilization? In his book, Harris sets out to discover what it means to build a better life, taking a personal journey from a landfill in Vancouver to Lake Louise’s otherworldly beauty.

In pivoting to a more direct search for meaning, Harris uses the word “blur” to describe his quest to grasp more ephemeral ideas and experiences. It’s a curious choice, but also apt, as he writes in an interstitial chapter that introduces the second half of the book.

“So, I began staring longer at those blurred spaces. Partly out of my desire for a richer view of things but also out of prudence — it seemed obvious that new modes of being would be required to survive the 21st century. We live by our stories and, if we can’t bring new narratives into focus — stories beyond the grand fairy tale of consumer culture — then we are doomed to live out of sync with reality.”

These fuzzy and illegible ideas come into focus in chapters titled “Craft,” “The Sublime” and “Care” that delineate ways to fashion a more honest relationship to both the material and immaterial world, whether that means building a birchbark canoe by hand or surrendering one’s ego to the glory of the natural world.

In searching for a new way to live, Harris returns to one of the oldest: the philosophy of Aristotle and his concept of eudaimonia. It is a tricky term to pin down, and in order to get a better understanding Harris interviews various people, including Edith Hall, author of Aristotle’s Way. As Hall explains, eudaimonia is not something you get, as much as something you do. “It’s a way of life and a set of behaviours that you decide, quite consciously at first, to implement.”

Happiness, a term that is often swapped for eudaimonia, isn’t exactly the same thing, and in some fashion winnows down the concept, stripping away its active nature. “Happiness is a lesser story,” Harris writes.

This sentence jumped off the page and slapped me lightly across the face. In the context of All We Want, it means that the endless pursuit of happiness as the ultimate good is an impoverished way to look at life. Put another way, happiness is only one aspect: it’s pleasant and all, but the endless concentration on it detracts from the world of other experiences that life offers.

In documenting the struggle between old and new, one system passing on and another not yet born, Harris does not spare himself. “This book chronicles a time when I, anxious in that half-blind state, twisted around looking for the missing stories. Whole generations are doing likewise.”

The new stories he finds, unlike the monomyths of old, don’t have any simple answers. “They’re not sexy,” he says. But they are human.

When I started reading All We Want, I thought I knew what I was in for, but the book heads off in unexpected directions. It is very much an essay, an attempt to get at something, to figure it out.

In this aspect, Harris has undertaken nothing less than trying to understand some of the more contrary aspects of human nature: not only our endless desire for more stuff, but our ability to fool ourselves into thinking that we can somehow escape intractable things like the laws of physics.

In the end, turning to face plain old reality — as opposed to pretty stories of baubles, fashion and fancy houses — we might get something different. Namely, another chance. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: