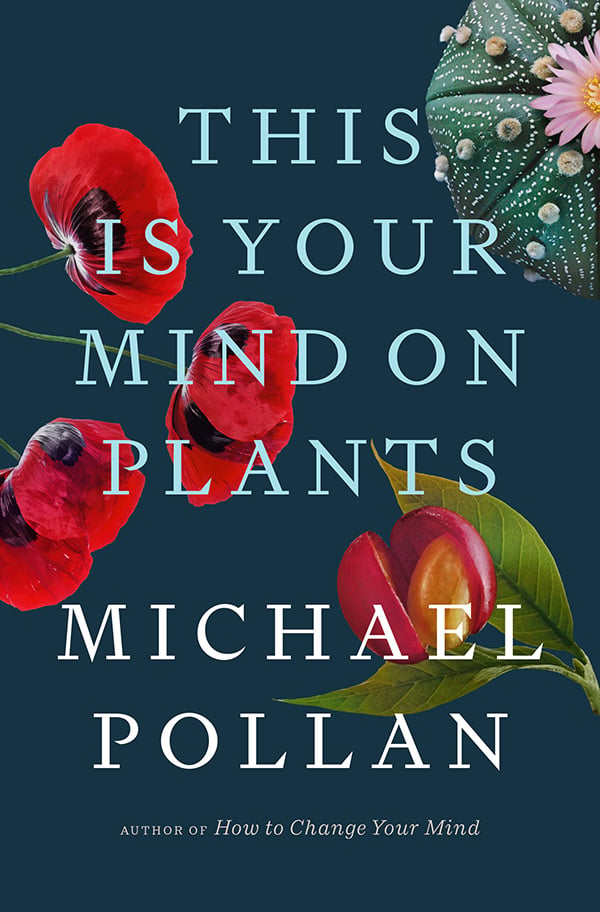

If you’re looking for a pick-me-up in these strange, sad days, Michael Pollan’s new book This Is Your Mind on Plants just might do the trick.

Continuing in the vein of his previous work How to Change Your Mind: What the New Science of Psychedelics Teaches Us About Consciousness, Dying, Addiction, Depression and Transcendence, Mind on Plants features the usual dense Pollan-esque research as well as a few trippy moments in the deeper realms of consciousness.

How to Change Your Mind saw Pollan trying an exhaustive number of substances — mushrooms, LSD and the vaporized venom of the Sonoran Desert toad, which the U.S. author describes as inspiring one of the most singularly terrifying moments that any human brain could countenance. “I watched the dimensions of reality collapse one by one until there was nothing left, not even being,” he writes. “Only the all-consuming roar. It was just horrible.”

In contrast, Pollan’s new work is limited to deep dives with three different plant-based drugs — opium, caffeine and mescaline. Just don’t do them all at once. Or maybe do and write your own book!

Each plant has a long and gnarled history, some good and some bad. But, as Pollan notes, it’s all in how you use it. A little can cure you, a lot will kill you. As is usual for humans, we are always changing our minds about stuff, and I’m not even talking about altering consciousness through the imbibing of different things.

“Nothing about drugs is straightforward,” Pollan writes. “But it’s not quite true that our plant taboos are entirely arbitrary. As these examples suggest, societies condone the mind-changing drugs that help uphold society’s rule and ban the ones that are seen to undermine it. That’s why in a society’s choice of psychoactive substances we can read a great deal about that society’s fears and its desires.”

The opening chapter of the book sprang out of an earlier essay about opium poppies that Pollan wrote for Harper’s Magazine. In 1996, when the article was published, the U.S. drug war was fully raging. When he ran the piece by the magazine’s legal department, the lawyers suggested excising the centrepiece, where Pollan demonstrated how easy it was to make opium tea using poppies from his own garden.

As he explains in Mind on Plants, his decision to self-censor was the only rational thing to do, given the potential repercussions (jail time, property seized, life ruined). He cuts out the heart of the essay and hides it away on a floppy disk at his brother-in-law’s house for 25 years. The saga of getting those pages back is a whole other story, the moral being that if you really want to keep something you’ve written safe, print it out on acid-free paper and avoid your in-laws.

In the years since Pollan wrote his Harper’s essay, the climate changed. Not only was the war on drugs a dismal failure, but in the interim, large corporations got involved in the trade. Purdue Pharma created a synthetic opiate and set about marketing the hell out of it. OxyContin and its cousins became one of the deadliest and most widespread health crises on the planet.

(Opioids killed thousands and doomed even more to the horrors of addiction. If you need or can bear to know more about this story, Alex Gibney’s documentary The Crime of the Century or Patrick Radden Keefe’s book Empire of Pain provide good overviews.)

Resurrecting the lost section of his essay provides Pollan with the opportunity to make redress to his writerly ambitions, but also to look at how much has changed in how we view these different chemical compounds.

The seismic reconsideration of drugs keeps unfolding, even since the publication of How to Change Your Mind in 2018. The vast number of studies underway on psilocybin, MDMA and other illicit drugs (heroin and opium, among others) is encouraging. Psychedelics hold particular promise. The therapeutic use of LSD for terminal cancer patients has been happening for a number of years, but psilocybin has also come into wider use to combat depression and PTSD.

But even if one is not popping LSD or magic mushrooms on the reg, many humans use some kind of drug every day. Most often it’s caffeine, via coffee and tea.

The strange circuitous history of the coffee plant makes it a worthy subject of study. Pollan excerpted some of his chapter on coffee in a recent essay for the Guardian.

In his quest to understand the impact of caffeine, Pollan quits cold turkey. In so doing, he comes to understand just how powerful a drug it truly is. Not only does caffeine create a baseline of functionality — being able to write, think and act are all aided and abetted by caffeine — but it is also bound up in daily rituals. The deep comfort of morning java and afternoon tea prove almost as hard to quit as the drug itself.

I can sympathize with Pollan’s experience, having started the coffee habit at age 11. I’ve only gone off of it twice, once while I was pregnant and the second time in some ill-advised health quest. Both times were horrible, and the eventual re-entrance of coffee in my life was like a holy benediction.

Of the three substances examined by Pollan, mescaline proves the most fascinating. Firstly, it isn’t easy to find. Secondly, it works in a way that is quite different from other psychedelics. Lastly, because there’s something of a battle going on around who gets to use it.

The last chapter of Plants revolves around Pollan’s desire to participate in a peyote ceremony (mescaline is derived from the peyote cactus.) The global pandemic throws a spanner in the works, but also the deep reluctance of Native Americans to have yet another white man seeking knowledge to use for his own benefit.

Pollan speaks to members of the Native American Church, also known as Peyote Religion. Some people are more forthcoming than others. But the church’s battle for the right to use peyote in ceremonies constitutes its own mini-drug war between some unusual parties, namely the Decriminalize Nature movement and Indigenous people.

As a new drug-policy reform movement, Decriminalize Nature has proven to be remarkably successful, with more than 100 local chapters in the U.S. As Pollan explains, “Decrim Nature has done a brilliant job of naturalizing psychedelics; in effect, reframing them as an age-old pillar of the human relationship with the natural world....”

But this success had some unexpected fallout. In the struggle between the “psychonauts” (Pollan’s term for people who use psychedelics as means to explore their inner consciousness) and Indigenous people who have long used peyote as a sacred plant medicine, there isn’t enough peyote to go around.

Mescaline in pure chemical form proves easier to access. When Pollan is gifted two fat capsules of mescaline sulfate, he pops them and settles in for a long ride. (Mescaline trips can last upwards of 14 hours.) With his recent re-read of Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, he’s somewhat prepared for what happens, but on drug trips, like much of life, things don’t always go as expected.

The intense feelings of being in a permanent present are one aspect, but it’s the ability to see very deeply and closely that proves to be something of a revelation.

“To say mescaline immersed me in the present moment doesn’t quite do it,” he writes. “No, I was a helpless captive of the present moment, my mind having completely lost its ability to go where it normally goes, which is either back in time, following threads of memory and associations to past moments, or forward, into the anxious country of anticipation. I was firmly planted on the frontier of the present and, though this would soon change, there was nowhere else I wanted to be or anything I needed from life in order to be content.”

All of which sounds kind of pleasant, and as he indicates, curiously befitting in the pandemic pause, when many of us were collectively forced to sit still for a moment. Like most transformative things, however, mescaline isn’t meant to be used every day, nor taken lightly. “Ordinary consciousness probably didn’t evolve to foster this kind of perception, focused as it is on being — contemplation — at the expense of doing. But that, it seems to me is the blessing of this molecule....”

The final section of the book, wherein Pollan and his wife participate in a communal overnight mescaline ceremony, is easily the most interesting part, and also strangely cheering, not in a facile or silly fashion but in a more elemental way. After a long night, with many cathartic moments, what follows in the breaking light of day is a profound feeling of gratitude and reconnection with people, plants and the planet itself. “Despair no longer felt like an option,” he writes.

I’d like some of that. ![]()

Read more: Health

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: