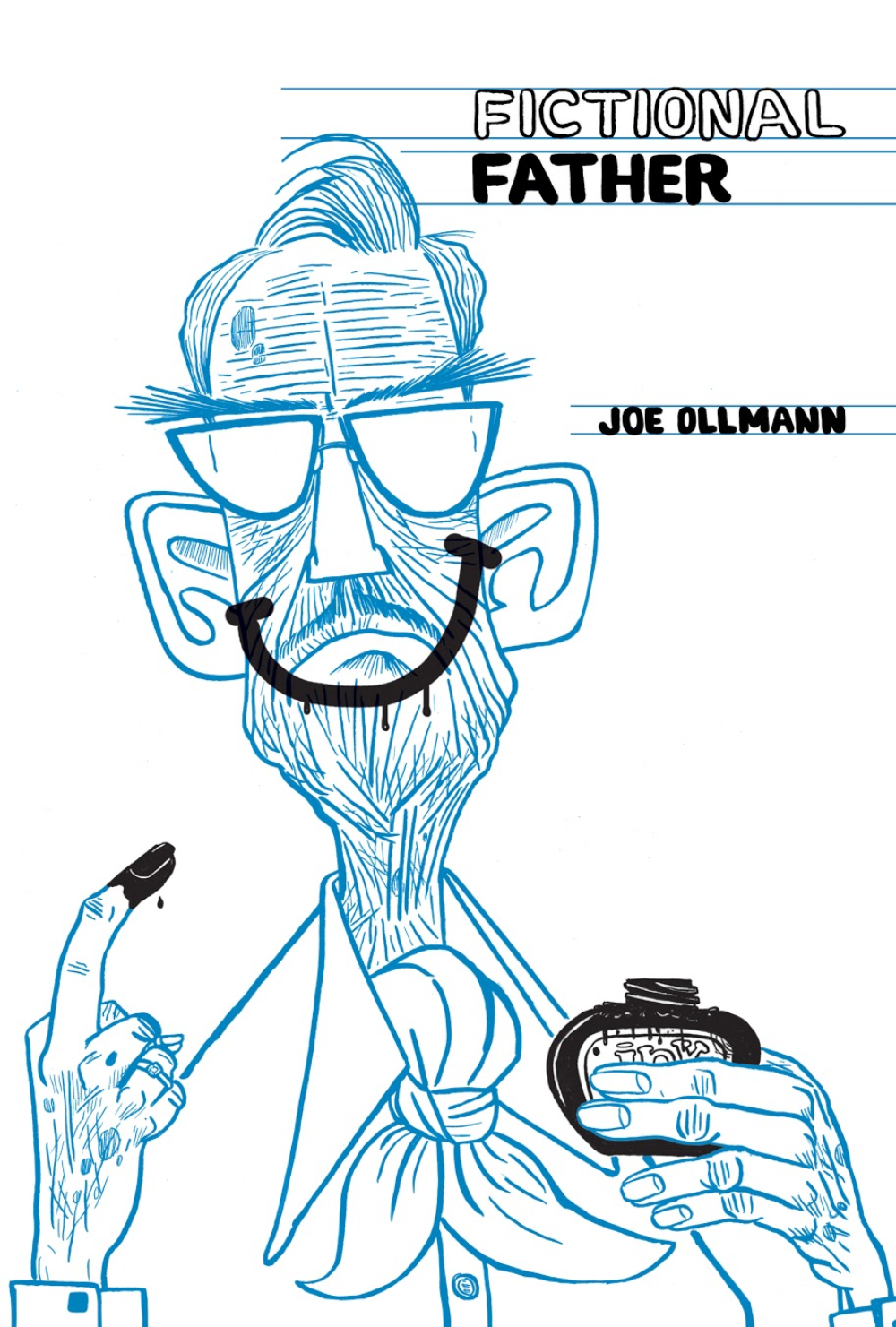

- Fictional Father

- Drawn and Quarterly (2021)

They don’t make ‘em like they used to. In the case of fathers, this is probably a good thing.

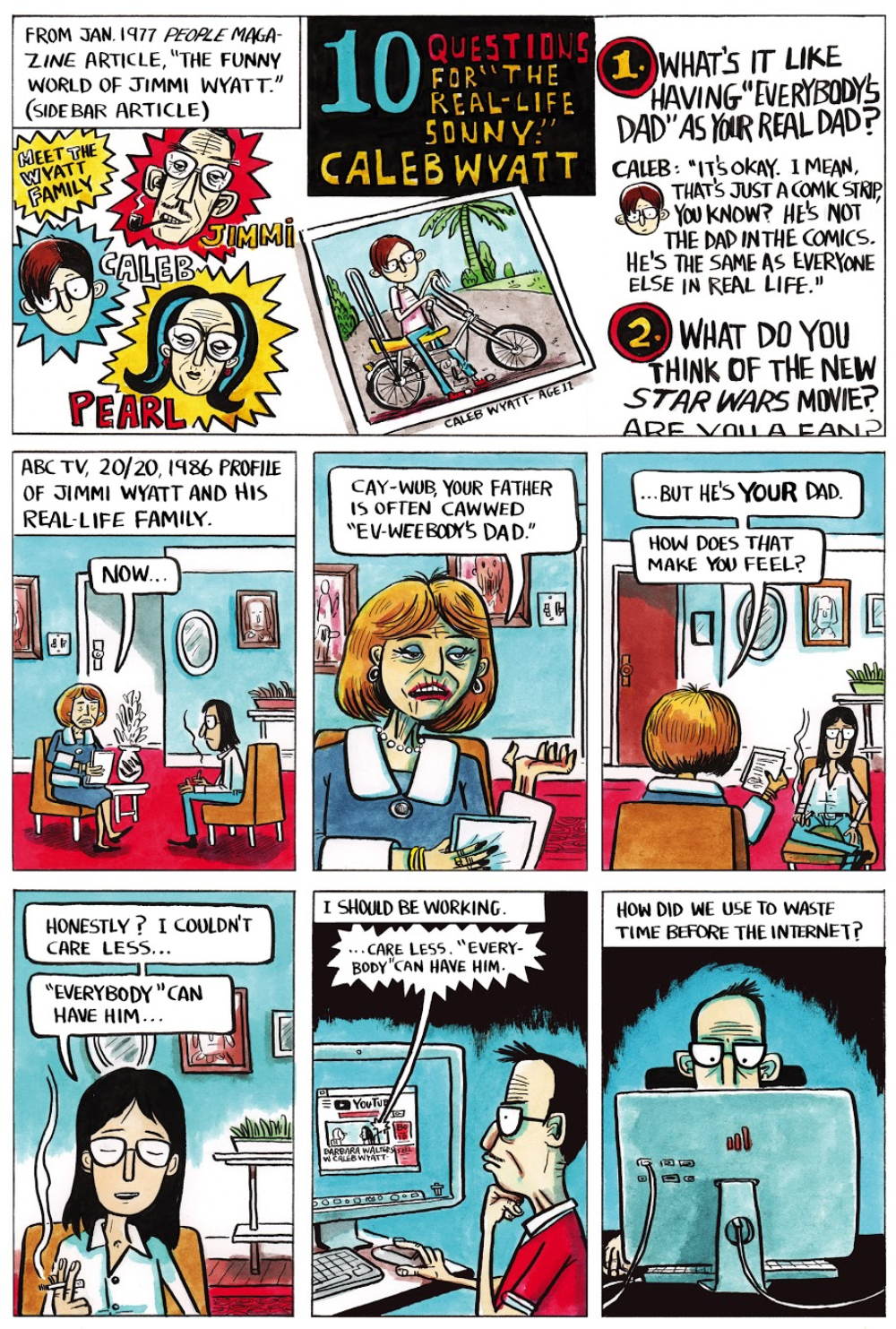

The central relationship in Joe Ollmann’s alternately hilarious and bittersweet graphic novel Fictional Father is that of famous cartoonist Jimmi Wyatt and his adult son Caleb. The world knows Wyatt as the creator of the daily cartoon strip called Sonny Side Up. Think Peanuts meets Family Circus, with a dash Father Knows Best sprinkled on top.

The tragic story of Hank Ketcham, creator of Dennis the Menace, and his real-life son offered a jumping off point, but Ollmann takes the idea of family dysfunction in unexpected and often profoundly emotional directions.

Caleb, a recovering addict and semi-successful painter, knows another side of his father, a nightmare patriarch of old with a penchant for skirt-chasing, supreme selfishness and a definite lack of interest in anything parental.

Taking aim at the dynamics of the nuclear family, as well as the lingering, perhaps surprising resilience of the old-time daily comic strip, Fictional Father is a nuanced and painful but ultimately humanizing look at family ties, punctuated with Ollmann’s scratchy, catchy, wonderful drawings.

Ollmann, a 55-year-old Hamilton-based cartoonist and author, is part of a generation of cartoonists, along with Seth, Peter Bagge and Chester Brown, some of whom pop up in Fictional Father playing their real-life selves. In addition to winning awards for his work, Ollmann co-curated This Is Serious: Canadian Indie Comics, an exhibition of Canadian artists working in a variety of forms (graphic novels to indie cartoons) that demonstrated the explosive outpouring of creativity and innovation in the genre.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: The character of Jimmi Wyatt recalls a lot of men of a certain generation, who prioritized work, ego and self over just about everything else. Do you think the old-style patriarchs slowly dying out, along with the comic strips that immortalized them, opens up room for new and different stories?

Joe Ollmann: I would hope that all old-style patriarchal everything is dying out! I think you can definitely feel a shift of the makeup of creators in the world of indie comics, which was largely almost exclusively white dudes not that long ago. There’s been a slow change of that demographic as more women, people of colour and the queer community joined the ranks and began telling other stories that had been largely neglected. More perspectives and experiences can only make a better comics scene, and one that reflects the readership as well. There’s even room for us old white guys.

You preface the book with a bit of confession about the origins of the idea of Fictional Father and the real-life relationship between Hank Ketcham and his son. Did this story surprise you?

Well, I tend to exaggerate for comic effect, an occupational hazard of being a cartoonist, I guess. So, I did know of the story of the real-life Dennis the Menace. I wasn’t consciously thinking of it when I began writing this book, but it must have been in my memory, of course. The stories are really only similar on a very basic level; a cartoonist famous for his portrayal of a loving father and son, who is a terrible father in real life. When my cartoonist friends reminded me that the story had its similarities to the real-life story of Dennis Ketcham, I decided to incorporate that true story into my fictional narrative.

How much of the story of Fictional Father came out of your immersion in the history of cartooning, in particular the golden age of the daily comic strip?

I have spent a life immersed in comics. As a kid, I loved reading those library compilations of Peanuts and Family Circus and Bloom County and even Wizard of Id and Doonesbury, which I never understood, but still always read. I’ve read the newspaper comics almost every day of my life. I’ve been obsessed with comic books from a moment I can pinpoint around age nine when I bought a copy of Spiderman and a Jack Kirby issue of Captain America. I didn’t understand anything that was going on, but I loved it and wanted more. I spent every cent I could beg, borrow or steal on comics from that moment on. I moved away from superhero comics when I discovered comics for grown-ups being done by Julie Doucet, Seth, Dan Clowes, etc. I realized those were the kind of comics I wanted to make.

I started thinking about doing a book on comics and cartoonists when I spent a couple of years co-curating a show of Canadian indie comics at the Art Gallery of Hamilton while I was starting to formulate this book in my head. I think being even more immersed in comics than usual made a book like this inevitable.

Do you see the graphic novel as an evolution of comics or is it a different creature altogether?

I think they’re related but separate art forms. The structure of the comic strip — setup, setup, setup, punchline — is a bit limiting to character and narrative development in a way that the longer form graphic novel is not. There have been some strips, such as For Better or Worse, or Gasoline Alley, that embrace that longer form narrative within the form of the strip with lengthy story lines and characters that age, grow and change. But mostly, the comic strip sacrifices narrative and character development for the sake of the gag. That’s its purpose, ultimately.

Caleb’s relationship with his father forms the centrepiece of the story, but his mother is an equally fascinating creation. The idea that we’re somehow destined or doomed to become our parents or at least embody some of their worst qualities is implicit. Is there a path out of this pattern?

There’s also an alternative to being doomed to taking on the worst qualities of our parents. You can emulate their good qualities too. I was lucky to have wonderful parents who had a genuinely loving, respectful relationship. If I had taken on some of those qualities, I would have been so much better at relationships over the years.

I guess just being aware of where your habits come from and self-correcting — we don’t have to repeat negative patterns. If we’re cognizant of them, we can change them. The mother in the book is an interesting character to me. She’s flawed and a bit cold and detached, but she’s aware of it. That awareness and her attempts to improve make her a better person than the father.

The relationship between aging parents and their adult children is rich turf. Did any of your own experience with your own parents find its way into Fictional Father?

Not at all, except maybe to juxtapose my nice parents against Cal’s terrible ones. I’m lucky! I have talked a lot over the years to friends who have unresolved issues with dead parents and their thoughts helped with the writing. I have adult children, so I probably looked at my own past parenting critically, though I’m no Jimmi Wyatt! My kid’s blurb on the back of the book attests to this!

In the balance between image and word, is there a battle going on between what to represent visually as opposed to verbally? Do the two always support each other, or do they occasionally go to war?

Hopefully it’s a harmonic juxtaposition, that’s the idea, except when you’re intentionally exposing an unreliable narrator with visual evidence to the contrary of their words. One of the great things about comics as opposed to traditional novels, is you’re somewhat in control of the reader’s imagination as the visualizations are not left up to their imagination entirely. As the creator, you are somewhat more in control of how you want to present your story.

Who are some of the artists/writers who have most influenced you?

In comics, the biggest influence in the way I approach writing is Lynda Barry. I am no Lynda Barry, but her work is branded on my brain like that of no other artist. I used to pay money to get Now magazine, a free alternative weekly, just so I could cut out her comic in there every week.

Influences are hard to name, as I feel like you can admire the hell out of someone and be influenced by their work and create something that feels nothing like their work. It’s a subtle influence of tone maybe. Other cartoonists that have made a big impression on my thinking are Dan Clowes, Julie Doucet, Seth, Chester Brown, David Collier, Frans Masereel, Michael Dougan, Sue Coe, Carel Moiseiwitsch, Adrian Tomine and the Hernandez brothers.

You’ve been described as a cartoonist’s cartoonist. What is it about the form that you find most compelling and the most challenging?

Ha! I wonder if that’s a compliment? I guess it is, but maybe my work is less accessible to a non-cartoonist? I’m going to take it as a compliment. I love making comics, so I enjoy all aspects of it. Though I feel more confident when I’m writing. I’m never completely happy with my drawing limitations. But as I get older, I’m harder on myself and redraw a lot and don’t let completely shoddy drawings go to press.

As legacy media continues to wither away in Canada, does it surprise you that the daily strip still persists? Why do people cling to it?

I’m a weirdo that subscribes to a local paper and can only really read properly on paper, so reading the comics in the paper is a daily ritual. Personally, it’s a force of habit and nostalgia that keeps me reading them.

When my dear old Dad was sick in his last years and I would visit — my parents both read the daily paper cover-to-cover — we’d talk about the comics eating breakfast. He had his favourites, and he had a good eye for the best of the new strips. I think of him when I read the strips he loved, it’s another connection.

A lot of the daily strips are awful, trying to get hip by adding modern references. Which I think misses the point; this is an old-fashioned, outdated art form. No one is coming to comic strips looking for commentary on modern society. I think they’re meant to be observations on the eternal human condition, removed from specifics of time and place? For all my critiques of newspaper strips, I love them, and they better never go away. ![]()

Read more: Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: