On the side of a federal building in Vancouver, a three-story, brightly coloured mural tells an amazing story.

It shows generous Indigenous paddlers offering food and supplies to immigrants from India trapped on the Komagata Maru after Canadian officials refused to let them enter Canada in 1914. The ship eventually returned to India, where 19 passengers were killed and others imprisoned as government tried to arrest them.

It’s a powerful image of cross-cultural solidarity.

But did it really happen?

Most people who have seen the mural — unveiled in 2019 with federal cabinet ministers on hand — had no reason to doubt it, Bal Dhillon among them.

“It was beautiful to hear that story,” said Dhillon, a Burnaby high school teacher with an undergraduate degree in history.

Dhillon had noticed the Punjabi word taike on the mural, which has a complicated history but can often mean “cousin.” He said he spoke with his immigrant uncles about it, who told him that as Punjabi Canadians they indeed considered Indigenous people like cousins.

Last month Dhillon wrote an article for The Tyee about the connections between two global movements — the farmers in India fighting the state-driven commercialization of agriculture, and the Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs in northern British Columbia fighting a natural gas pipeline in their territory.

The comparison was not meant to create a “false equivalency,” Dhillon wrote, but to explore what might be learned from the two peoples’ resistance to corporate and state power and their shared deep connection to land. He wrote about the mural, and the paddlers’ support of another group oppressed by a racist, colonial state.

But after the piece was published, three academics who have variously researched the Komagata Maru and South Asian histories wrote to The Tyee, arguing the story could not have happened.

One of them is Ali Kazimi, an associate professor of cinema and media arts at York University. He directed the documentary Continuous Journey and wrote Undesirables, both about the Komagata Maru.

“One of the things you have to understand is the Komagata Maru is a remarkably documented event,” said Kazimi, who’s been concerned about the mural’s historical accuracy since it went up.

Kazimi, along with Hugh Johnston of Simon Fraser University and Anne Murphy of the University of British Columbia, say they’ve never come across any accounts of Indigenous paddlers helping the ship’s passengers.

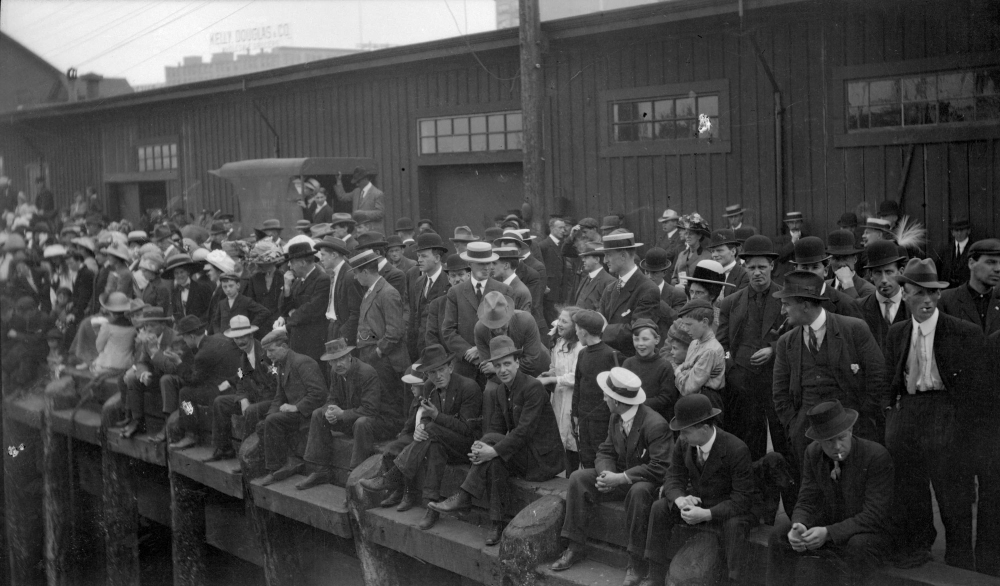

And with the ship under armed guard and intense media scrutiny, the three don’t believe the paddlers could have approached the Komagata Maru unnoticed.

The power of stories

Naveen Girn, the curator of the mural, believes it shares an important account of solidarity between Indigenous people and persecuted Indian migrants, as both were oppressed by colonial power.

Kazimi and the other scholars who have researched the Komagata Maru’s history say not only is the story untrue, it “discredits” the starvation and suffering that the ship’s passengers at times endured.

Stories have power. And as B.C. wrestles with its colonial legacy, the mural debate highlights questions about how history is recorded, and especially the weight given to oral history and colonial records.

There’s often an implication that an archive or the documentary record is complete, said Susan Roy of the University of Waterloo, an associate professor who studies Indigenous history and oral histories.

Her disclaimer: “An archive is only a representation of what’s been collected.”

Official records from a time such as the 1910s in a place like B.C., “privilege the bureaucracy or government perspectives of the story,” said Roy. “Though you can sometimes uncover voices of marginalized communities in those documents as well, such as through testimonies and petitions, or through photography and other kinds of records.”

As for the story depicted on the mural, Girn says it originated from oral accounts passed down from the Komagata Maru’s passengers.

In Canada, oral history has been deemed legally equivalent to other types of evidence since the Supreme Court’s 1997 Delgamuukw versus British Columbia ruling, which considered it in assessing Gitksan and Wet’suwet’en treaty rights.

What makes a strong oral history are checks and balances to ensure accounts are accurate even without documents or physical evidence, say experts.

But the mural’s history — and the challenges to its accuracy — show a debate continues, one with important consequences for our understanding of the past and reconciliation.

A description of the mural, sponsored by the Vancouver Mural Festival and the Indian Summer Festival in 2019, says it was inspired by “oral accounts by both South Asian and Musqueam community members that have recently surfaced that suggest Indigenous people assisted the passengers with food and supplies during their two-month-long period of deprivation.”

The description adds that the mural is “inspired by that possibility.”

In an interview with The Tyee, curator Girn stands by the accuracy of the story as he heard it, but also stressed that the mural is a “highly symbolic and imaginative piece.”

The voyage of the Komagata Maru, an infamous episode highlighting the racism of the Canadian state, has always drawn attention from the press.

Reporters took great interest as the drama itself unfolded in 1914. One newsletter headline at the time read: “Hordes of Hungry Hindoos Invade Vancouver City.”

The ship was chartered by Baba Gurdit Singh, a successful businessman in Southeast Asia who heard how fellow Sikhs were being prevented from immigrating to Canada due to discriminatory policies.

Potential immigrants had to undertake “continuous passage” from their country of birth or citizenship to Canada. This no-stops-allowed rule was created to keep Indian immigrants out, as the journey by sea would be too long.

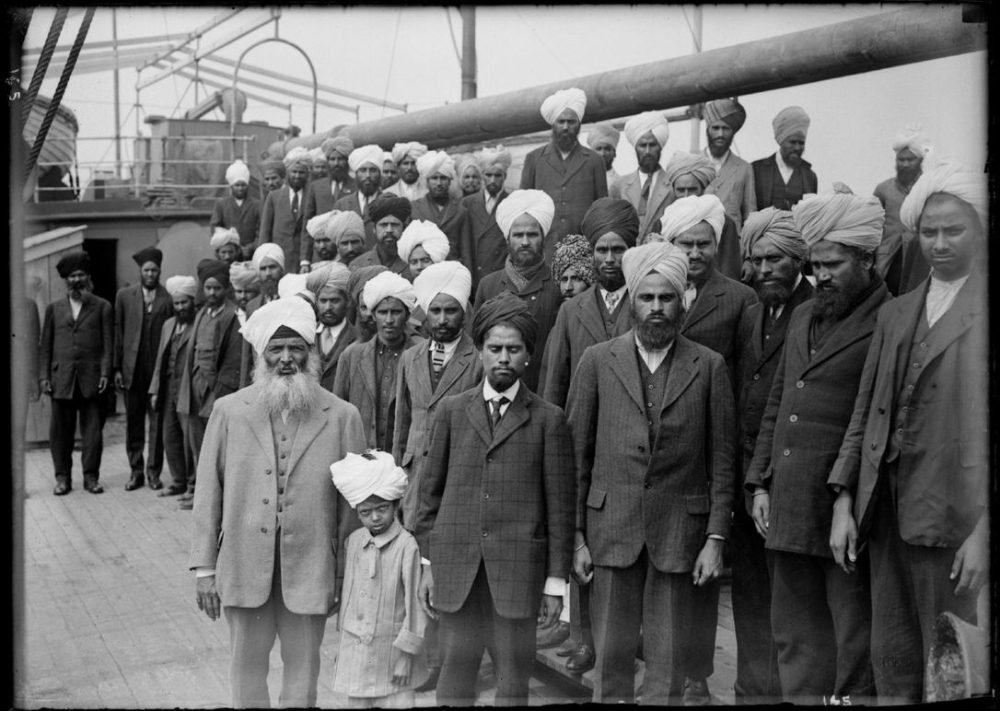

The Komagata Maru embarked from British Hong Kong on April 4 carrying 376 passengers, mostly from British India, who wanted to immigrate to Canada. It made continuous passage to Vancouver Harbour, anchoring on May 23, 1914.

But Canadian authorities prevented the ship from docking. It sat anchored until July 23, when it was escorted out of the harbour by Canadian military.

After a stop in Japan, the Komagata Maru then sailed to Budge Budge, India, where the government tried to arrest those onboard. Nineteen of the passengers were killed by gunfire and many others were imprisoned.

Food and water were a key part of the Komagata Maru story. During the two months that the passengers were stranded onboard, immigration officials strictly limited their supply of food and water at times to the point of starvation and thirst. Passengers became ill, and flies and rats gathered.

Of supplies and solidarity

Girn works on historical exhibitions outside his day job in the provincial government. In a recent interview, he said he’d heard the story of the Indigenous paddlers from Nadeem Parmar, a local writer known for his poetry.

Contacted by The Tyee, Parmar said he heard the story from the late Giani Kesar Singh, the author of books on the history of Sikhs in Canada.

Singh had interviewed Komagata Maru passengers who mentioned that Indigenous people in “small boats” had come up to the ship to sell fish and other goods, drawn to the “circus” of an event, Parmar said. Some passengers asked for help and offered money to be taken to shore.

But there was no mention of whether the Indigenous paddlers offered aid to the passengers. Parmar stressed that his conversation with Giani Kesar Singh on the matter was short, and that he passed the anecdote to Girn.

Girn said he concluded that the paddlers were likely Musqueam given where the ship was anchored in Burrard Inlet.

“It just makes sense that in this space in Vancouver, that would be the nation that would’ve done it,” he said, though it’s possible they could have been Squamish or Tsleil-Waututh.

Girn then shared the account with a Musqueam Elder, he said.

“Her response was ‘If Musqueam had greeted the ship when it had come, this is how we would’ve acted, because this is how Musqueam has always acted when newcomers come... providing a greeting.’”

At a centennial memorial for the Komagata Maru hosted by the Musqueam in 2014, Wade Grant, a former band councillor, said something similar. “We would have embraced them much as we welcomed the Europeans,” Grant said. “We are impacted by the same racist policies and we feel the same pain passed to generations.”

The story of the Indigenous paddlers with goods and the Musqueam mention of a “welcome” gave Girn the idea for the mural.

When asked about the academics’ criticisms that the delivery simply didn’t happen, Girn said the mural is not a “photograph,” a “primary-source document” or an “eyewitness recording.”

“It’s an artistic interpretation of that moment,” he said. “I’m conveying what’s been told to me from people who I respect who have done strong work in this field and using that to create a mural... This is not an Uber service, for instance, where food was asked for and delivered on a daily basis. No one is claiming that.”

Rather, the mural points to how Indigenous and Indian histories have “intersected,” Girn said.

The Tyee emailed two Musqueam Elders as well as two members of the First Nation’s archives and research department to ask about any records of the story in January, but has yet to receive a response.

Also last month, The Tyee called the Musqueam’s communications co-ordinator for assistance, but since then the staffer could only find one of the mural’s artists, Alicia Point, to be interviewed.

“I really enjoyed working on it,” said Point, who said she first heard the paddlers story when she was asked to contribute to the mural. “Even the people in the building who were working came out too, and they wanted to help.”

Point’s parents are from the Chehalis and Kwantlen First Nations, and she married into Musqueam, where she lives. For the mural, she enjoyed watching Coast Salish motifs and the Punjab’s folk embroidery, called phulkari, come together in one work.

Aside from Indigenous paddlers in three boats with supplies, the mural includes a map of where the Komagata Maru was anchored, coastal mountains, orcas and a thunderbird, which Point said was known for being a protector and keeper of the past and future, fitting for the mural.

The Tyee was also able to reach Debra Sparrow, a Musqueam knowledge keeper, weaver and graphic designer.

Sparrow believes she’d heard of Indigenous paddlers near the Komagata Maru before work was underway on the mural, though she deferred to the mural team for the definitive account of the story’s origins. Her grandson was one of the artists, and she spoke at its unveiling.

Sparrow said she knows helping people in need was something the Musqueam people did, “even helping the colonials who came to colonize.”

Intermarriage between groups was common then, so it can’t be said whether the paddlers were strictly Musqueam, she said.

“We were probably happy to see other brown people,” said Sparrow with a laugh, adding she’s half serious.

On the importance of oral accounts in her community, she added, “Those words form our history, just as a book has written information in it.”

The Tyee was unable to find anyone to confirm the story of direct Indigenous aid to the passengers of the Komagata Maru — only the Punjabi community account via Singh of paddling vendors in the water.

Of tangible and intangible histories

The unveiling of the mural in 2019 was accompanied by a key event: the federal government’s stripping of the building’s name.

The Harry Stevens building was named after the racist MP and businessman who worked with immigration officers to prevent the Komagata Maru’s passengers from coming ashore.

The unveiling of the artwork depicting Indigenous-Indian solidarity, combined with the stripping of Stevens name, were seen as powerful symbols of decolonization. Publicity followed and the trio of academics watched as the story of the paddlers spread.

The federal government published a release that said the mural “recognizes the generosity of local Indigenous Peoples in providing food and water to the passengers.”

This was later repeated by broadcast outlets such as CTV and print outlets such as the Salish Sea Sentinel and the Indo-Canadian Voice.

Kazimi said he was on the examining committee for a PhD student last summer whose research cited the story of the paddlers via such news sources.

“I found it shocking and chilling that this would enter academic discourse — and in fact, a PhD thesis — so quickly,” he said, adding that the story is “not only deeply embedded in media, but it’s also seeping into academia.”

Kazimi believes that the fact that The Tyee didn’t question the mural’s accuracy shows the “dangers of presenting speculations as facts are self-evident,” because this “‘imaginative’ history is circulating as fact.”

He wants to see the mural festival and the government issue a statement to correct their descriptions of the mural.

Curator Girn said that just because there isn’t tangible evidence in government records doesn’t mean that paddlers didn’t approach the Komagata Maru. A large portion of the records about the ship came from Stevens, the racist politician, he noted.

“The archive is a colonial construction,” said Girn. “It has very deliberate perspectives on who it sees as a valid source of history. And archives only have a very limited scope of who they reach out to, to collect resources from documents, artifacts... If we were to just rely on the archive to tell the stories of marginalized communities, we wouldn’t have the resources to tell those stories.”

Girn says he’s made an effort to source stories and artifacts from non-white communities in all the projects he’s worked on to fill in the historical “gaps.”

“Every exhibition I’ve worked on has included some elements of oral storytelling and working outside the archive,” he said. “That’s because these histories were never considered ‘worthy’ of collection and preservation. There are power dynamics and implicit value judgments in place when stories are collected.”

He gives the example of a 2020 exhibit at the New Westminster Museum on the history of Sikhs in the city, which included new oral histories as well as albums and Sikh weaponry lent by families.

But Kazimi stresses that a colonial archive is not the same as colonial history.

“We all recognize as scholars that, yes, there is a particular colonial bias to the archive, but you can’t reject it carte blanche,” he said, adding that rereading colonial documents with new frames is essential for decolonization.

“Oral histories that emerge after a century need to be balanced by reference to other sources. We’re not talking about oral history for a period that has no documentation.”

Even if he were to accept the paddlers story as true, “the questions get larger and larger,” he said.

“The specifics don’t hold up when you look at the time,” said Kazimi. “If this is verified, then the passengers were lying that they were hungry, and it would discredit the exact passengers that this is being done in honour of.”

There are other better-known stories of intercultural solidarity in Vancouver’s early years.

For example, the Squamish people conducted a key rescue mission during the Great Vancouver Fire of 1886. From the community of Ustlawn on the North Shore, they paddled towards the city to rescue those who jumped into the inlet.

And even concerning the Komagata Maru, a shore committee of Indian Vancouverites offered assistance, raising money to hire Joseph Edward Bird, a leftist lawyer and white ally who believed that Canada’s immigration laws were racist. The committee also hired a Japanese fishing boat — as no white fishers were willing to do this, said Kazimi — which was allowed by the immigration officials to deliver supplies to the passengers.

But Kazimi hasn’t found much evidence of early interactions between South Asian newcomers and Indigenous people. The little he has uncovered has to do with lumber. One 1914 document captures a dispute over logs in Musqueam.

There were, however, close relationships between the Musqueam and Chinese newcomers who leased land from them to farm.

‘Information has consequences’

So, what happens when a new oral history emerges without documentation?

“Good oral history tellers always tell where they got the information from,” said Keith Carlson, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Indigenous and community-engaged history at the University of the Fraser Valley.

Carlson did not study the Komagata Maru and spoke to The Tyee regarding oral histories based on his own experience as an academic and his nine years as a staff historian and research co-ordinator for the Stó:lō Nation.

Western society has come to think of tangible records as memory, from “books on shelves to hard drives,” he said. But the oral histories of Indigenous communities can be as rigorous as scientific inquiry, requiring corroboration and facing challenges, even if there is no physical evidence when they are transmitted, Carlson said. At a potlatch, witnesses might back up an oral account that is shared or raise questions.

“Indigenous people are very concerned when you’re transmitting familial ancestral rights, properties, names, rituals across generations,” said Carlson. “People are usually very careful to cite oral sources. A knowledge keeper or Elder will say where they heard it from. It’s important to the validity and veracity of those narratives... As we try to create a more just society, Indigenous people and their stories, their histories are inevitably tied to their rights and title.”

If a new story pops up, Carlson says it’s important to learn whether or not it really happened as “physical reality.”

But he adds that “interrogating the motives behind why people might challenge or promote something on either side is equally important.”

“Information has consequences,” said Carlson.

In the case of the mural, the new Punjabi community account of Indigenous vendors in boats “inspired” an artwork that depicts direct aid. And now, there are conflicting understandings of what it means to respect the legacy of the Komagata Maru.

For high school teacher Bal Dhillon, whose Tyee piece led to the discussion of this tangled web of stories, the question of whether the mural tells a true story is fascinating.

But he’s focused on our situation today.

Whoever might or might not have been on the water during the summer of 1914, Dhillon says solidarity is still needed between the communities who struggle with the legacies of colonial power.

“We can talk about the validity of an oral history, of course, but we should also talk about the erasure that takes place when we talk about colonial history,” he said. “Those two things have to be spoken about in the same breath.” ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: