“The climate is most beautiful; the strawberry vines and peach trees are in full blow… All the colored man wants here is ability and money... It is a God-sent land for the colored people.” Wellington Moses, a member of the Pioneer Committee quoted in Crawford Kilian’s book Go Do Some Great Thing.

In the spring of 1858, hundreds of bright-eyed migrants arrived in Victoria harbour on a flimsy vessel named the Commodore. Many of them were giddy with excitement, hoping that what they would find, as advertised, Gold! Found on the Fraser and Thompson Rivers!

But among the passengers were 35 desperate people in search of something else.

They were the Pioneer Committee, a delegation of Black travellers fleeing California, which, having already legislated racism, was now sliding towards pro-slavery. Weary from the five-day voyage from San Francisco, the group disembarked, booked a large room from a local carpenter and settled in for an evening of praise and worship, each member surely filled with dreams of life and liberty, solace and asylum.

The circumstances surrounding the committee’s arrival were serendipitous and politically expedient. Victoria was a sparsely populated trade company outpost stumbling towards becoming the seat of a colonial government. A frenzied gold rush had just begun in the Fraser River canyon. The U.S. Supreme Court had just ruled that Black Americans could not be citizens of the United States. And the decisive and autocratic governor of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, increasingly concerned by the spectre of American annexation, needed a “counterweight to Americans.”

What the Pioneer Committee went on to find — a welcoming “land of strangers” with the support of the governor — would pave the way for the mass emigration of Black people from California to what would become known as British Columbia. B.C.’s Black settler pioneers, many of whom were eager to participate in colonial politics as equals, also discovered they must face what they’d seen already, a game tipped against them and rules that eternally bend in a convex arc away from justice.

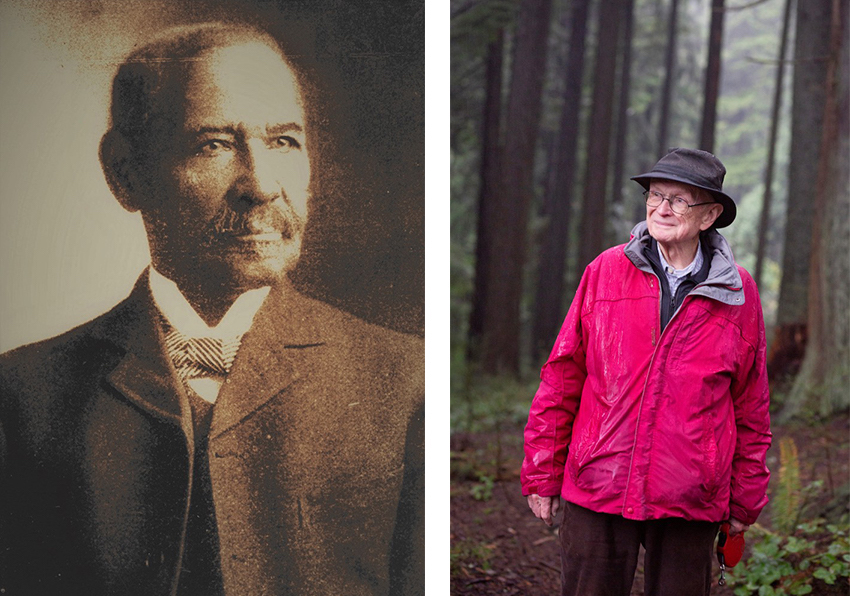

Crawford Kilian was “surprised and interested” to learn about this rich history by reading Margaret Ormsby’s British Columbia: A History. That was more than four decades ago. At the time he was teaching writing at Capilano College and authoring fantasy and science fiction novels. He decided to try and write his first non-fiction book. Go Do Some Great Thing: The Black Pioneers of British Columbia became a foundational text, especially for anyone who’s read through the histories of B.C. or walked through its halls of power and thought, “Where is everyone else?”

Now the book has been re-edited and re-released by Harbour Publishing, with a new foreword by Dr. Adam Rudder and an update. And Kilian continues in his role as Tyee contributing editor, having published hundreds of pieces here since his first in 2003. Regular readers of these pages will find Kilian in fine, familiar form in the latest edition of Go Do Some Great Thing, breezing through complex political histories in his clear and immediate voice dipped in a healthy dose of moral conscience.

When The Tyee caught up with Kilian over email, he said has been doing some “serious” dog-walking these days and was “just reflecting on having been born in World War II, enjoying the insane luck of my generation, and now book-ending my life with a pandemic and the fall of the American Empire.”

He discussed how he decided to write Go Do Some Great Thing, what it was like to republish it 42 years later, and why such a uniquely consequential group of people deserve more attention in other historical texts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Tyee: Do you remember how you decided to write this book in the first place?

Crawford Kilian: I ran across a brief mention of the Black pioneers in a standard history of B.C. I found myself saying, “Black people? Here?” The more I looked into it, the bigger the story became, and I realized it could be the subject of a book. I did more research, wrote a couple of chapters, and published a letter in the Vancouver Sun asking to hear from people who knew about the pioneers. Scott McIntyre, of the new publishing house Douglas & McIntyre back then, wrote back asking if I had a publisher and if not, could he take a look at what I’d written. He liked it, and the book came out in 1978.

What were you hoping to accomplish with Go Do Some Great Thing?

I thought the Black pioneers had a remarkable story, and they deserved far more attention than they had received. A UBC MA thesis on the pioneers was the only detailed account, but then it was almost 30 years old, hard to get hold of and lacking a lot of detail. I’d found much more material in the Royal BC Museum and Archives, and I also interviewed some descendants of the pioneers. So this was a chance to tell the pioneers’ story in some detail.

The book is pretty expansive, telling the stories of many of the important figures in B.C.’s Black history. You seem particularly interested in the story of Mifflin Gibbs. What about him drew you in?

Gibbs is one of my heroes — a young Black guy who arrived in San Francisco with a dime in his pocket and became a successful merchant and advocate for his community. He repeated his achievement in B.C., and then some. He was the first competition for the Hudson’s Bay Company, a real estate speculator, a Victoria city councillor who put the city’s finances in order, and the builder of B.C.’s first railway — carrying coal from a mine in Haida Gwaii to tidewater. Then he returned to the U.S., where he became an elected judge in Arkansas, a political operator, a banker and a U.S. consul to Madagascar. When he died in 1915, he was probably the richest Black man in the country.

But with one project and political battle after another, he must also have been really hard to live with! His wife Maria had studied at Oberlin College, and he’d brought her to Victoria around 1860. She was probably the best-educated woman in B.C., but stayed a private person. She left him in the late 1860s and went back to Oberlin, but he seems to have stayed on good terms with her and their kids.

Mifflin Gibbs and his family showed the opportunities open to Black people here in the 1860s — but also the limitations that made many of the pioneers return to Reconstruction America [after the Civil War]. If Gibbs had stayed, he might have been our first Black premier.

How was the book received when it was first released?

Actually, it was received too well. I’m not a professional historian, and I hoped a professional would go beyond my book and write a definitive account of Black British Columbians’ history. Instead, the book became the standard, and you could find it in almost every public library in the country. That was nice for me, but I knew how much of the pioneers’ story remained untold. And eventually the book went out of print, and people began to forget the story.

Why did you settle on Go Do Some Great Thing as the title?

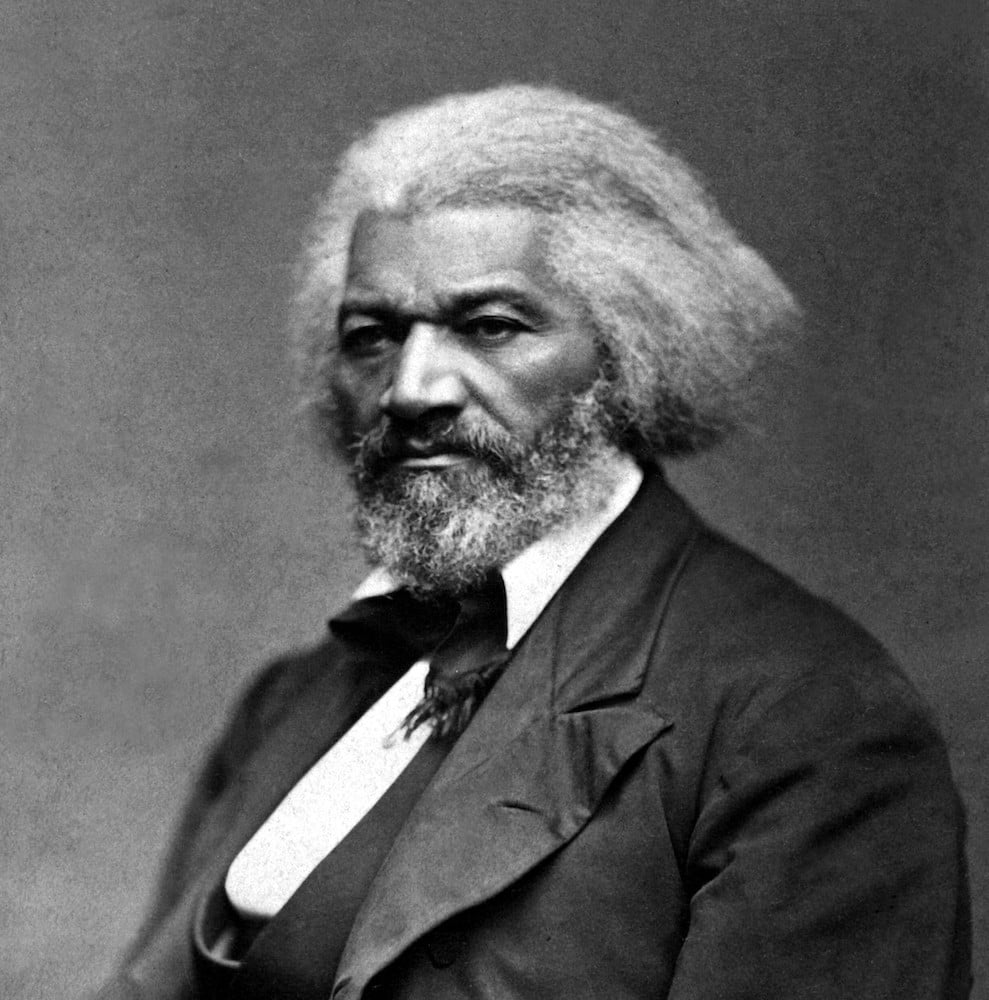

Gibbs was a kind of young understudy for the great Frederick Douglass on an abolitionist speaking tour in the early 1850s. It was a wonderful experience, but at the end of the tour he didn’t know what to do with himself. Douglass’s business manager was a no-nonsense white Englishwoman named Julia Griffiths. She changed his life with her response to his moaning — “What, discouraged? Go do some great thing!” That sent him to gold-rush California and everything that followed.

Griffiths’s advice applied to most of the Black pioneers. Whether enslaved or free, they had reached a California that hated them on sight. They had done pretty well even so, but they wouldn’t stay in a country whose Supreme Court had just decreed they could never be American citizens. So when the opportunity of migrating to B.C. arose, they seized it.

How are you feeling about the book’s re-release?

Amazed and delighted. The Black writer Wayde Compton and I produced a second edition in 2008, but we didn’t have the resources to do a serious update. The edition got little attention and soon disappeared.

How did this third edition with (Harbour Publishing or Douglas and McIntyre?) come about? Why now?

Douglas & McIntyre was acquired by Harbour Publishing some years ago, and last spring Howard White of Harbour Publishing emailed me to ask if I’d be interested in a new edition. Of course I was. The Black Lives Matter movement was under way, and Canadians were beginning to realize they were involved as well.

I see that partial proceeds of the republish will be donated to the Hogan’s Alley Society. Could you talk to me more about how that came about and why?

Hogan’s Alley was Vancouver’s Black community in the first half of the 20th century. Some of the children of the original Black pioneers settled there, and the Black porters on our railways often had homes near Hogan’s Alley. It was cleared to make room for the Dunsmuir Viaduct, but today’s Black community is doing a lot to revive our understanding of the role that Black people played in building the city. Go Do Some Great Thing is a contribution to that community.

Your book went through a substantial update for the republish.

Modern publishers often save money by cutting down on editing. Not in this case. I’ve always liked editors because they’ve taught me so much about writing (and saved me from endless embarrassment!). But this was superb editing on every level from fact-checking to choosing just the right words.

What’s different, then, about this latest edition?

I can now see that the first and second editions were written from a white perspective, which today sounds both patronizing and tone-deaf — not only toward the Black pioneers but toward the Indigenous and Asian peoples who had their own parts in this story. I owe that insight to my editors also. But I hope all my readers, whatever their ages or backgrounds, will judge it as a story about people like themselves, trying to make a living and build communities. And I hope some of my readers will go deeper into that story than I could. The more they learn about the Black pioneers and their world, the more they’ll learn about themselves and world we’ve inherited from them.

What does it mean that no one else fulfilled your hopes by writing an additional, different history involving the Black pioneers? The book you wrote in 1978 is still pretty foundational in our understanding of the experiences of Black people in this province. What does that tell us about history making?

History is proverbially written by the winners. But sometimes the winners begin to realize they got only the booby prize, that they completely missed the real point of the contest. At that point history moves from self-congratulation to self-education. And not a damn minute too soon. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: