John Horton is the person you’d be really glad to see if your boat was taking on water off the coast of British Columbia. He skippers the 52-foot Delta Lifeboat, a volunteer leading volunteers ready to come to the rescue of sailors in need.

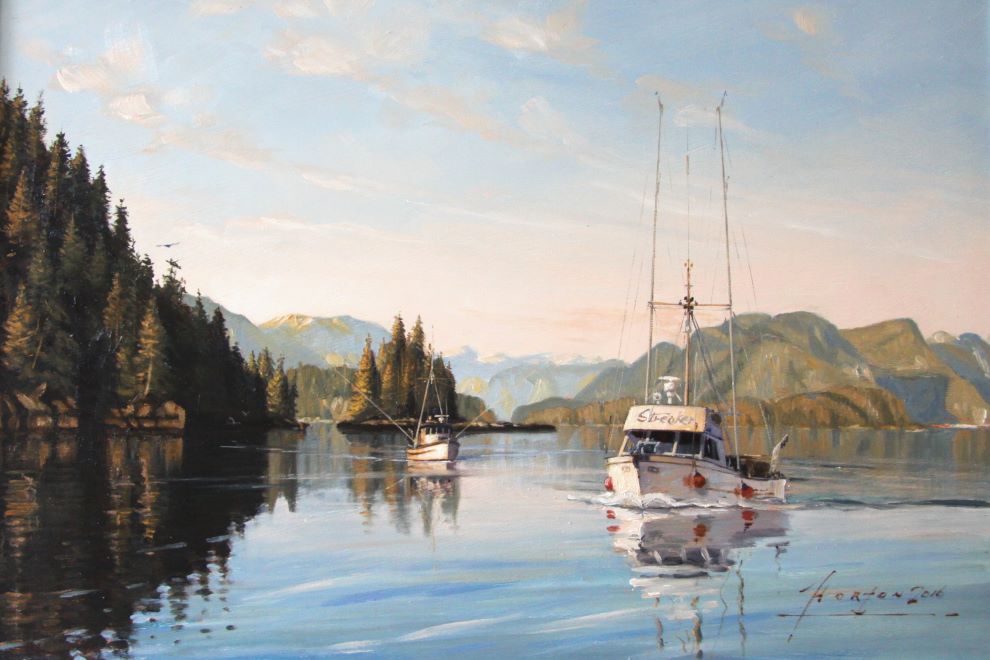

Horton has been at this sea hero stuff for quite a while. He is now 85-years-old and in range of his thousandth rescue. Helming the Delta Lifeboat, though, is something he does around the edges. His day job is world-famous artist. His lauded nautical paintings, including of voyages by captains Cook and Vancouver, hang in major museums and private collections. His work appears, too, on minted coins.

Suffice it to say that when Horton received the Order of British Columbia earlier this month, he seemed, well, almost overqualified.

Who better to check in with then, in this first of an occasional series on fascinating people who also happen to be Tyee Builders? Yes, John and his wife Mary kindly support independent journalism with monthly contributions to The Tyee and we are grateful.

It was Mary who dropped an email to us saying, basically, hey did you know that one of your supporters is getting B.C.’s big honour? Mary’s pride in her husband is fully reciprocated. “Mary, she is my rock,” says John, “and we are a wonderful partnership.” Their romance is one of those great second acts that life graces the fortunate, as we shall see.

Let’s start, though with John’s voice on the phone, plummy as Admiral Nelson’s must have been, explaining his path to painting, then the sea and then a life full of both.

Growing up in England, “I had a serious road accident when I was four-years-old. I was run over by a car. The doctors discouraged me from sports, telling me I might break even more bones. I gravitated to art.”

He wanted to be a naval architect, but he lacked the math gene. Instead, mentored by a brilliant artist named Vic Barber, he ended up making watercolour sketches for a top architecture firm in London, where he lived with his first wife and young family.

One day a Canadian opera singer arrived in London, and her husband became a workmate of Horton’s. He was from Vancouver. The year was 1966 and “you could not open an English newspaper without reading a full-page ad urging people to move to Canada,” Horton remembers.

“What’s Vancouver like?” Horton asked his friend, who the next day brought a dozen White Spot placemats covered with pictures. “I took them home, threw them on the table and said to my wife, how would you like to move there? She filled out the immigration papers right away.”

In Vancouver, Horton quickly gained plenty of work rendering for local architects, and the marine-themed paintings he exhibited drew buzz, and clients.

That the sea would be his muse was inevitable. As a young man he’d enlisted in the Royal Navy. His last posting put him aboard a ship tasked with protecting British vessels in the North Sea. “It gave me a tremendous empathy for what commercial fishers go through. There wasn’t a day that went by we didn’t see injuries. It was as though we were a floating hospital.”

In Vancouver, Horton joined the civilian corps of the Coast Guard Auxiliary. Sometimes he’d help rescue a sailor who had bought one of his paintings. But the coast guard called the shots and Horton wanted more latitude in who and how he could help. His team, for example, would come to the aid of a foundering boat, engines dead, but once it was clear the boat wouldn’t sink, the coast guard masters would say no to towing it to shore.

So in 1988, Horton decided to fund and head an independent search and rescue operation staffed by volunteers and currently based in Ladner. Its Delta Lifeboat, once a U.S. navy launch used by Admiral Chester Nimitz, is owned by and registered to Mary and Horton, who operate it under a charter agreement with the Canadian Lifeboat Institution, one of 22 similar organizations around the world. Mary and Horton contribute, with others, donations that pay for training, gear and fuel.

“I’d like to say right here and now I share this [Order of British Columbia] award with so many of my volunteers. Without them I couldn’t do it,” he emphasizes.

The mission of the Delta Lifeboat, says Horton, is to “help any mariner in distress,” from kayaker to freighter. But a special target is the fishing fleet. When a fishery opens, Horton and his crew of five to 10 will stay at sea with the fleet for the duration. During the latest herring fishery off Comox, the Delta Lifeboat was there in minutes to attend three major incidents — a crushed hand, a lost finger and a sinking vessel.

The Saturday afternoon I chat with John on the phone, he’s just back from safeguarding boats carrying out a brief Indigenous fishery at the mouth of the Fraser as massive ships plied the same waters. He and his crew helped “keep nets free of deep sea shipping, working closely with pilots, skippers, to make sure the river is safe,” explains Horton. “Fishermen really appreciate what we do.”

The adventures stowed in memory are many. Horton retrieves “one of the most, shall I say, exciting ones.” It happened “some years ago” on “a filthy night.”

A gillnetter was in trouble three miles north the Sand Heads, which lie beyond the mouth of the Fraser. “It was blowing 25 knots, and he’d be blown into the surf line along the bank. We managed to get up there and we were towing him back toward Sand Heads.” Suddenly, mysteriously, the tow rope went slack. “The foredeck came right off the fish boat, with the cleat still attached,” Horton recalls. Ahead in the darkness stood the Sand Heads lighthouse on pilings, about to suck in the fish boat.

“We yelled to the captain standing on what was left of his foredeck, ‘Take the line and tie it onto your stern and we’ll tow you!’” It worked. Everyone got out alive, but for Horton it confirmed what he’d been told by many mariners. For vessels without powerful engines, the Sand Heads, with its strong tides, deceptive shallows and fierce storms, “is the most dangerous piece of water in all of Canada.”

Moments like that over decades have given Horton a keen appreciation for famed mariners of yore. He’s a particular fan of captain George Vancouver, whose reputation he believes was falsely maligned by rivals.

Nothing can erase the fact that Vancouver heralded the arrival of colonialism, with devastating consequences for peoples who’d been here for millennia. But within that context, Vancouver showed respect towards Indigenous people, Horton says the record proves. It is false that Vancouver’s “clean” ships brought devastating disease, and was a lie, promoted by an unruly seaman relieved of duty, that Vancouver was cruel, Horton maintains. To date, he has made 50 paintings of Vancouver’s charting of the Pacific Coast.

But instead of a historical debate, I promised at some point a romantic interlude, so here goes.

As a veteran of the Royal Navy, Horton had long been a member in good standing of HMCS Discovery, the naval reserve base at Stanley Park. There he and his wife often would see Mary and her husband. “We used to go to all the functions.” But about two decades ago, each of their spouses passed away within a year of each other. Explains Horton, “We cried on each other’s shoulders, so to say.”

It’s a good thing they forged a knot. As John tells it, Mary is a “very good photographer. She has an eye for things.” The pictures she takes vitally inform his paintings, of which there are more than 1,400.

A Delta Optimist article about Horton says that as he readies himself to paint, he “pores over original naval architectural plans, renderings and ships logs. Patrons have observed that in viewing a Horton canvas, one can determine the season, the time of day, the atmosphere and even the temperature.

“He makes no apologies for his quest for perfectionism. ‘I’m never satisfied with what I’ve done,’ says the artist. ‘Every brushstroke I do must be better than the last one.’”

To that preparation Mary lends computer research, for John is not one to Google some famous ocean journey. He just won’t. “I’m not a computer guy.”

Wait, John. You give to The Tyee and you don’t use a computer? “I do not spend time working on a computer. I am not going on the computer.”

Whatever John knows of what The Tyee publishes, therefore, he gets second-hand from Mary.

So here’s a special thanks to Mary, for telling John about The Tyee. And for telling The Tyee about John.

What a fantastic voyage the resulting hour on the phone turned out to be. ![]()

Read more: Art

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: