Claire Adamson spent a year studying how people got along with one another in Richmond’s 45-acre Minoru Park.

Her big question for them: What connects you with strangers in the park?

“Duck attacks!” a woman told her. “Usually I see something funny, like a couple arguing on the benches or a kid being cute. I just make eye contact with someone and a conversation starts, because you both know you saw the same funny thing.”

Look at a map of Richmond, and you’ll see how sprawling it is — something researchers say hinders community interactions.

Like many suburbs, Richmond separates residential areas, malls, office parks and farmland. People spend a lot of time in cars, with fewer chances to interact than in more walkable places like Vancouver.

And because of Richmond’s large immigrant population, mostly Chinese, newcomers can exclusively spend time in community spaces catered to cultures they are used to, from Chinese-language churches to Chinese-catered malls.

That’s why shared spaces like the central Minoru Park play an important role in creating connection in suburban Richmond, British Columbia’s fourth largest city.

Adamson researched exactly how the park helps people connect in meaningful ways through everyday interactions for her 2019 master’s thesis in urban studies at Simon Fraser University.

She collected interviews and observations through four seasons, taking notes on everything from family outings and high school sports to hospital workers on their lunch breaks. She defined connection as a sense of belonging, trust and safety and shared interests and experiences.

“Minoru Park is like Richmond’s Central Park,” said Adamson. “There are a lot of really deep emotional connections that people have with the park.”

“Before my father passed away, we used to run the remote-control boat in the lakes,” a man told her.

“I let my toddler run around,” a woman said. “I come here for my anniversary every year too. We were married at the chapel.”

Minoru Park — originally a racetrack that opened in 1909, named after King Edward VII’s Irish-bred racehorse — is located in what’s considered to be the city’s growing downtown, near homes, offices and rapid transit.

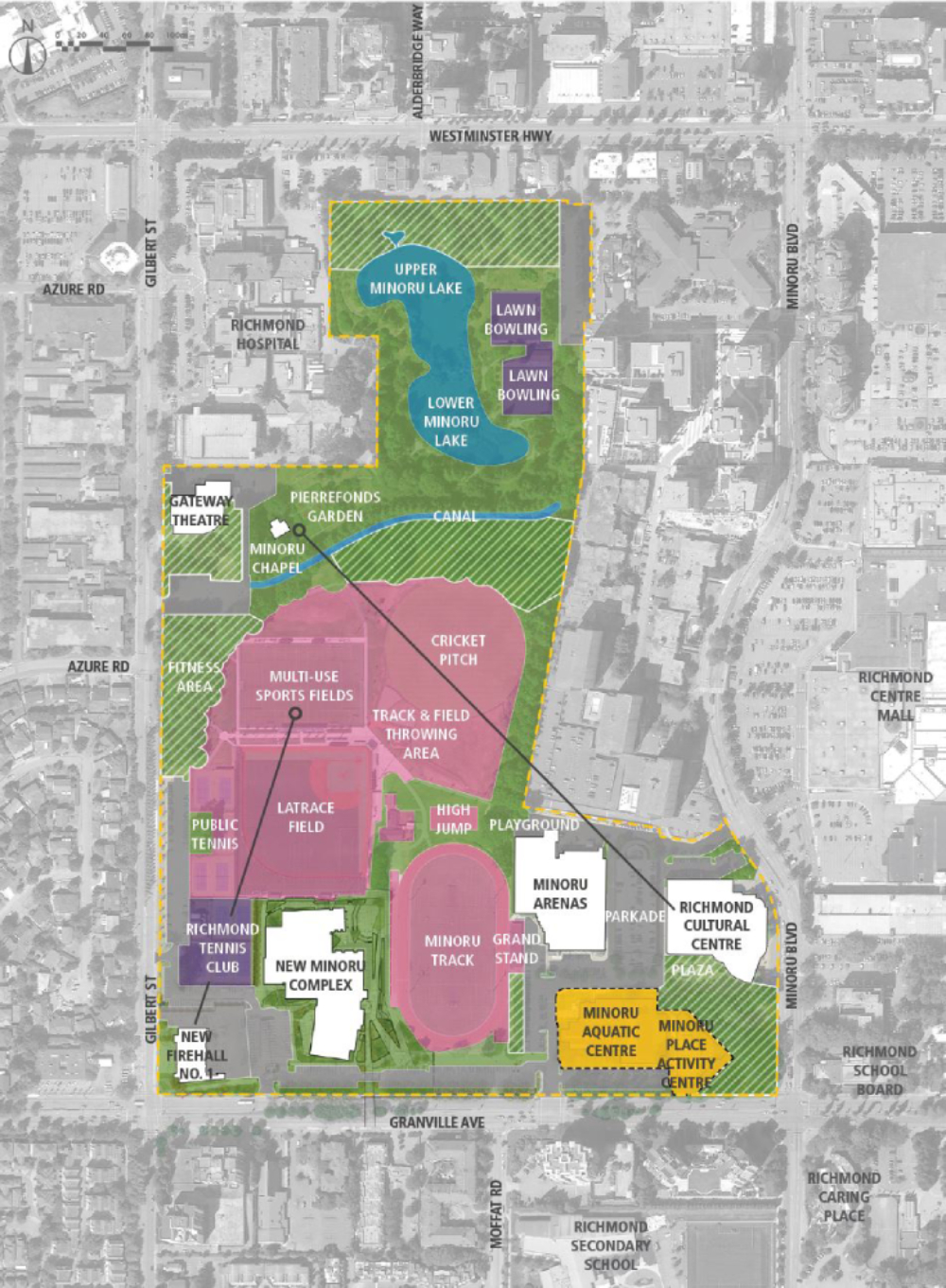

In the north, by the Richmond Hospital, are the lakes and the bowling greens. Further down is The Chapel at Minoru Park. Clustered in the southern half of the park are tennis courts, a track and the playground, with indoor activities including the rink, the pool and the library at its southeastern corner. Frisbee games, marching cadets and snoozers on benches are all common sights.

Having a variety of things to do encourages interaction, because activities like walking a dog or watching baseball can break the ice. Animals, Adamson found, were among the best conversation starters, and the park has an abundance of wild rabbits and ducks.

Sociologist Elijah Anderson calls places like Minoru Park “cosmopolitan canopies,” urban oases where people of different backgrounds can mingle.

“All the research demonstrates how important it is to have places where people can visit, walk through and be passive while having those encounters,” said Adamson. “When people gain that exposure to difference, it builds a level of comfort.”

Accepting difference is a lesson that some Richmondites are struggling with.

Richmond is one of Canada’s “majority-minority” cities. About 76 per cent of the population identifies as a visible minority, according to the 2016 census. This spiked in the 1980s with Hong Kong immigration, and continues today with Chinese immigrants from the mainland.

Some English-speaking locals have complained of feeling excluded by this demographic change, lobbying city hall to limit Chinese signs and ads and going on social media to complain about everything from service at Chinese restaurants to Chinese immigrants’ driving habits.

Last fall, in a spat over strata rules, a Richmond man was caught on camera saying, “I hate the fucking Chinese, you know.”

Adamson encountered those attitudes.

“I often feel isolated in parts of Richmond,” wrote a non-Chinese Facebook user quoted in her thesis. “I am tired of seeing signs in characters, and I have no idea what they mean,” wrote another.

A piece of social infrastructure like Minoru Park is a great place for Richmondites to get exposed a cross-section of their neighbours in a leisurely setting. Famed urban designer Jan Gehl believes public space is a “great civic equalizer,” because everyone can access it and hierarchical roles and expectations are often forgotten.

“When the plaza is alive — I’m not talking on an event day — but just on a good day, when the sun is out, people play the piano...there’s osmosis,” a man in his 40s told Adamson. “People’s kids play, and kids don’t care if you’re Chinese, white, autistic, dress different or whatever, they just play. And then parents start to connect. It just happens.”

“Look around,” another man in his 30s told Adamson at the park. “Every nationality is here, and every sport team is diverse that way.”

On a day Adamson brought her dog to the park, she connected with a Chinese-speaking grandmother as they both encouraged her young grandson to pet the dog.

Though the park isn’t free of cultural tensions, sometimes it’s due to a simple misunderstanding, Adamson found.

Some English-speaking parents noted that Chinese-speaking grandparents seemed to discourage their grandchildren from playing with their kids, and wondered if the Chinese grandparents looked down on them. But Chinese-speaking park users revealed the Chinese-speaking grandparents simply didn’t want their grandchildren to bother others.

Adamson concluded that people have different ideas of what’s considered the “appropriate” or “ideal” way to behave in a park.

“For some people, the most friendly, respectful thing you can do is greet someone and interact and play,” she said. “For others, it’s to give space and respect someone’s quiet enjoyment of the park.”

And just because language is an obstacle, it doesn’t mean there aren’t other ways to communicate.

“A nod or smile shows an acknowledgement that you’ve seen that other person,” said Adamson. “It’s friendly, it’s polite, it’s convivial, but it also demonstrates that it’s a safe place.”

As Adamson spent time observing people in the park, she found out that people were also observing her. A woman who passed her twice seemed standoffish until a man said hi to Adamson. After that, the woman felt comfortable enough to say hi.

In another case, after Adamson chatted with a man, a girl came up to her and asked if the man was bothering her. In the winter, when Adamson was using a path, people told her to watch out for a frozen puddle up ahead.

And when Adamson was measuring how well-used a playground was by counting the number of children, a man suspicious of her attention came up to her with a “May I help you?”

These experiences proved that people in the park felt responsible about taking care of one another.

“Jane Jacobs used the phrase ‘eyes on the street,’” said Adamson. “The research shows that really adds to the social value of a space.”

Repeat encounters also help Minoru Park users know one another by sight and by reputation; there’s a 103-year-old woman and a man who practises swordplay who are known to many.

Parks aren’t magic fixes for disharmony, but they help set the stage for interactions. Encounters and repeat encounters help increase users’ care for the park and the people in it, says Adamson. “Cities would benefit from seeking to understand better the meaningful nature of ongoing, commonplace, day-to-day sociability,” she says.

Adamson finds that even the slightest of smiles and nods have a role to play in fostering community and connection in a diverse and occasionally divided suburb.

“It might be said that getting up and going to Minoru Park provides the people of Richmond an opportunity to put some distance between themselves and the divisive discourses,” she writes in her conclusion.

As one park goer told her, Richmond could do with more osmosis.

You can read Claire Adamson’s thesis “Public Life in Minoru Park: Community Connection in Richmond’s City Centre” here. ![]()

Read more: Urban Planning + Architecture

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: