When Ho Tam and Ranee Ng thought about what to name their exhibition of zines, pamphlets and other artifacts from Hong Kong’s protest movement, they remembered the protesters, the tear gas and the police brutality.

And they remembered the chanting crowds — especially the masses of protesters chanting “Freedom cunt! Freedom cunt!”

They had their name.

The English slur “cunt” is pronounced as “hi” in Cantonese. So the exhibit became “Freedom-Hi!: Zines from Hong Kong's Civil Movements.” The two words captured the spirit and goals of the protests, Ng told The Tyee. “We are using every way we can to see if we have the chance of meeting freedom, to say ‘hello.’”

The exhibit sprang from a serendipitous encounter between Tam, a Hong Kong-born, Vancouver-based independent publisher, and Ng, a Hong Kong artist of Zine Coop. Tam told a mutual friend he was interested in exhibiting printed material that had come out of the protests sparked by a proposed amendment to the existing extradition bill that would specifically allow criminal fugitives to be handed over to Taiwan, Macau and mainland China. Protesters fear mainland China would abuse extradition power, using it to punish opponents.

The friend thought Tam should meet Ng, who had recently moved to Vancouver, and promised an introduction. But before that happened, Ng showed up at Hotam Press, Tam’s publishing company, with recent Hong Kong resistance zines in hand. Thus began their collaboration on this exhibit.

What draws Tam and Ng together and motivates them is a relentless passion for printed matter and civil movements in Hong Kong. Tam, who has long been observing Hong Kong’s civil movements from afar, has struggled with being unable to participate in the protests. Ng, who discovered Hong Kong’s culture of independent publishing and zines in university, is motivated by the radical potential that alternative printed media has to resist mainstream media and its narratives.

“I also learned about zines, self-publication, and realizing that outside of the mainstream media there are some things that are supplementing history first-hand on different perspectives,” explains Ng. “So other than [Television Broadcasts Limited] or newspapers, there are many other sources of materials for us to look at.”

“This was really enlightening for me. Because once upon a time I only had authority news.”

Hong Kong, a former British colony, was returned to China in 1997 under the “One Country, Two Systems” agreement that promised to protect its independence until 2047. Hong Kong has made headlines in recent years for its civil movements in pursuit of democracy. In the Umbrella Movement protests in 2014, protesters occupied various parts of Hong Kong for 79 days to demand universal suffrage. But the iconic yellow umbrellas of the movement eventually closed; demands were ultimately ignored by the government and leaders of the movement were jailed.

Five years later, the people of Hong Kong find themselves back in a familiar place. The anti-extradition bill protests, which have escalated since June 2019, demonstrate a growing frustration with Chief Executive Carrie Lam’s indifference to the demands of the Hong Kong people, police brutality against protesters and an increasing fear of what the future of Hong Kong will look like after the city-state’s economic and political autonomy ends.

Ng said this time the movement is “decentralized” and has “no leadership.” People with various skill sets show up where they are needed and operate within their own domains.

“You can see that many people have been using their special skills and abilities to advance this cause. This time everyone has been saying ‘Be water,’ so other than referring to using the tactic of assembling and disassembling quickly during protests, it also refers to permeation and flexibility in the movement,” she said.

The Tyee sat down with Tam and Ng at Hotam Press to learn about the role of zines and other printed material in the protests, lessons learned from the Umbrella Movement and the creative and humorous sensibilities within Hong Kong civil movements.

This interview was conducted in both English and Cantonese and has been edited for clarity and length.

The Tyee: How did you come up with the name of the exhibit “Freedom-Hi”?

Ranee Ng: This phrase actually originated from a live news broadcast from Stand News [an independent media outlet in Hong Kong]. There was a large amount of tear gas being used and police were conducting “pursuit and attacks” on citizens, so protesters hid behind the glass door and there was a confrontation... and then the police, during the live broadcast, yelled “Come out, pig cunt!”

The protesters heard “freedom cunt” — that’s how this term originated. It was quite noisy and chaotic, but people kept saying “Freedom cunt! Freedom cunt!” and that’s how this term came to be.

Ho Tam: Actually, I’m really interested in this word, because it’s very controversial. At first when I was watching on YouTube and saw people wearing clothes with the words to the demonstration, I was really shocked. So, around the time we were planning this show, I thought of this term. Using English, it’s not that offensive and it seems a little bit weird and if you understand one of the meanings you will think it’s quite interesting. It’s a more radical way of attracting the audience.

This is a tactic sort of like queers using “faggot” or calling themselves these terms. Even “queer” is sort of a term like this, a long time ago. I wanted to reference that kind of activism or reverse the situation; when people call you names, and you take it and become empowered by it.

Ng: One day there was an audience member who said using “freedom-hi” is reclaiming this term. It doesn’t matter if people call you names, you can use your own way to perform this term.

I feel like we have tried all kinds of ways, and can we see freedom yet? Can we say “hi” to it yet?

How do you feel about being away from Hong Kong right now as everything is unravelling/happening?

Tam: In a way, it’s kind of distant for me because I don’t have a lot of relatives or friends who live in Hong Kong so I’m not really so in touch. But I feel that in my blood, I am somehow Hong Kong-ese or still somehow kind of connected.... To me it’s very close to my heart.

Ng: Really tired. I really can’t sleep. Once you wake up, a couple more news stories break. You don't know how the world has changed. Every day you don’t know what tomorrow will be like. You feel really powerless. What can you do? Even if you were in Hong Kong, what would you do? I think to myself, if I was in Hong Kong, what would I do? Would I be on the frontlines? Honestly, I’m not brave enough. I still have responsibilities at home. I definitely will not be at the very frontlines.

What is the role that zines and printed matter play in Hong Kong’s social justice movements?

Ng: Through my past research, I noticed that in the 1970s Mok Chiu-Yu and his friends created a publication called 70s Biweekly. Is it a zine? I’m not sure how to define it, because the Chinese definition of zines varies, and I still haven’t reached a concrete conclusion. But I think zine is not about the materials or printing methods or subject matter, but it’s about the spirit. The spirit of being true to your own voice. I feel like the 70s Biweekly is a quite powerful publication that I’ve found so far.

During the ’70s they were talking about the Baodiao movement and anti-war information. The origins are also quite “zine.” It began because the mainstream media had really unfair reporting of the students of Chu Hai College of Higher Education and a monk who saw this reporting was really upset and gave the students $6,000 to create their own newspaper and amplify their own voices.

During the Baodiao movement, or during resistance, they may slip some messages in their publication about the date and time of when they will gather and rally or march. Not only did they provide a platform for their own voices, it was also a call to action, and everyone could contribute to the publication and participate; this was a really important platform.

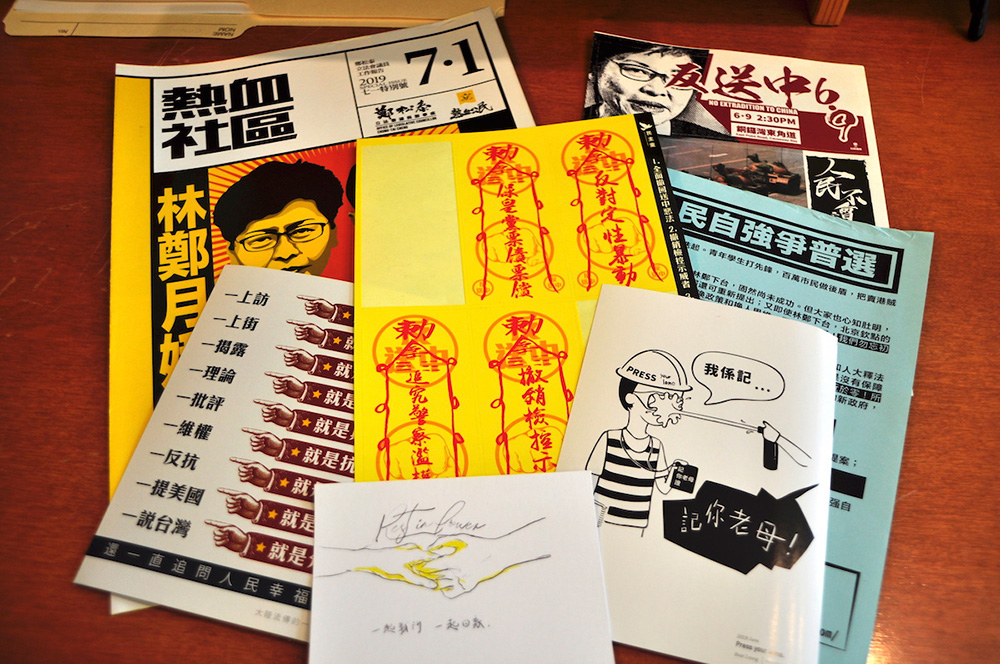

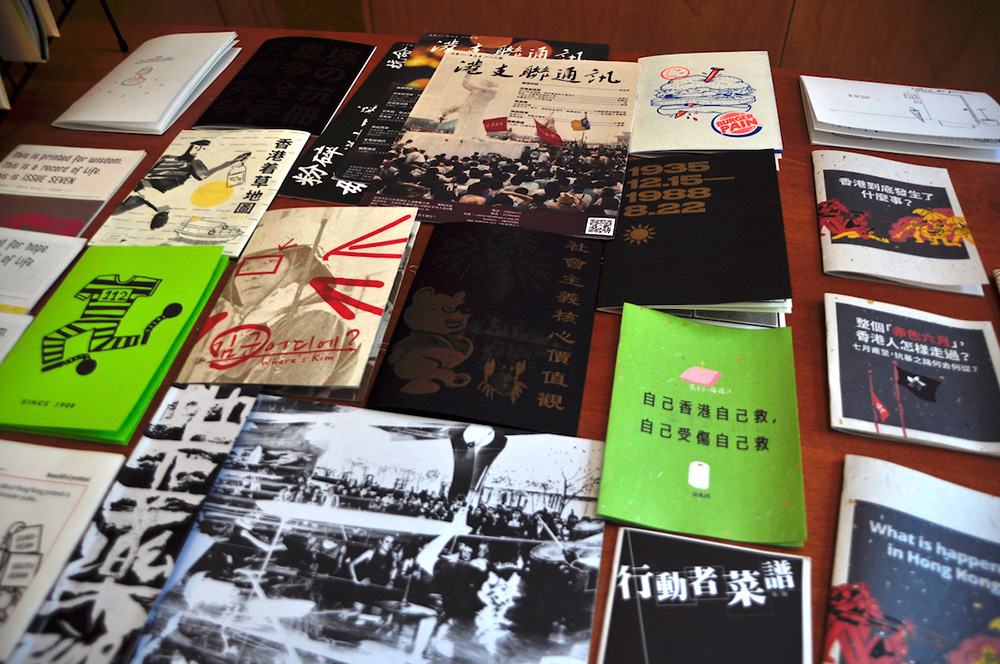

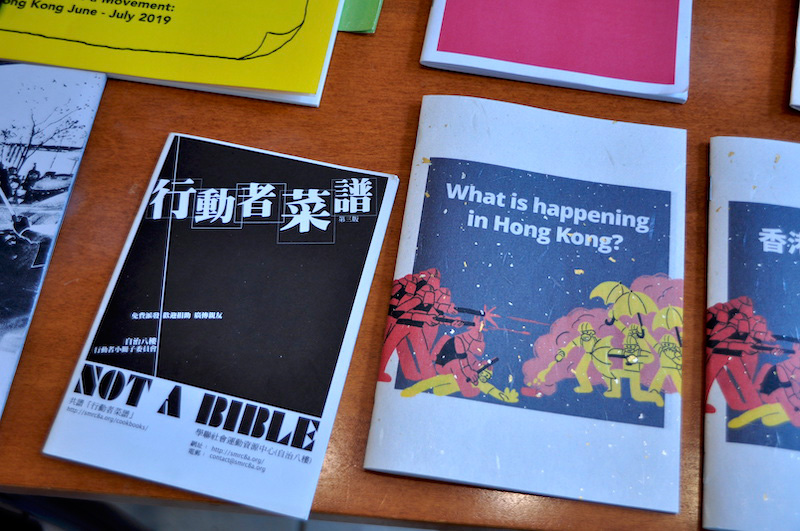

In fact, during the anti-high speed railway protests, Umbrella Movement, a lot of people would create their own publications. It’s true this time as well... But this time I think the most amazing part is this thing of “open source.” How netizens have utilized the online platform as a means for communication. Before you would only come in contact with the end product at the protests, like receiving someone’s leaflet or zine or stickers, but this time people have shared the power and responsibility with you. You can print those leaflets. They have mobilized the use of printed matter as a broadcasting tool. I think this time around print has been a big help or for people to realize that it can be really powerful.

Why do you think Hong Kong people were able to produce this kind of printed matter so quickly?

Ng: It’s because this time people have deeply internalized the lessons from the Umbrella Movement... I really think it is a collective learning and self-reflection process.

Of course LIHKG online forum and Telegram groups are very instantaneous forms of communication. Not only can you see the news, Stand News, these reporters’ live streams, but as a participant at any point you can instantly have a form of communication. As I said earlier, this time around people just show up. There are design small groups, printing small groups, translation small groups; this kind of information can travel really quickly and, in addition to everyone’s professional division of labour, has allowed this kind of material to appear so quickly and so well.

Ho Tam, since you’ve been based in Vancouver for a while, how do you see printed matter and zine culture being applied to social justice movements here?

Tam: I think this is something I don’t see a lot in Vancouver. There are some people doing certain things. I live in basically the Downtown Eastside, and there are some activists that use the media or use self-publishing or independent publishing as a means to distribute ideas, but it’s very limited. I don’t see them getting out from their immediate surroundings or the community. So I feel like it’s not something that is so popular.

It’s still quite young and limited. I think the audience is very limited at this point. And that’s exactly what I’m interested in, trying to promote independent publishing in the city or bringing in different publishers or artists to show here as well. And regarding this show about these Hong Kong zines, I have been doing my own kind of sharing to bring some attention. I have a lot of Canadian and international friends and they might not be aware of what’s going on or they do not understand. I think one of my ideas is to bring them to the show and try to explain the situation to them without being too didactic or too harsh. I think people can really respond to it.

What can the zine-scene, self-publishers or activists take away from this particular exhibit on printed matter and social movements in Hong Kong? What could they learn?

Tam: One of the things that I asked Ranee to help to prepare is the background information. I stressed that we want to have some news clippings, and then also I provided comments from the internet and often they will translate it into English too. There are different points of view or citizens’ point of view that I want to get across. That’s sort of the idea. I think that’s my hope. Just kind of seeing “Oh this is day-to-day life for the Hong Kong people.” That’s what I’m interested in bringing to the public.

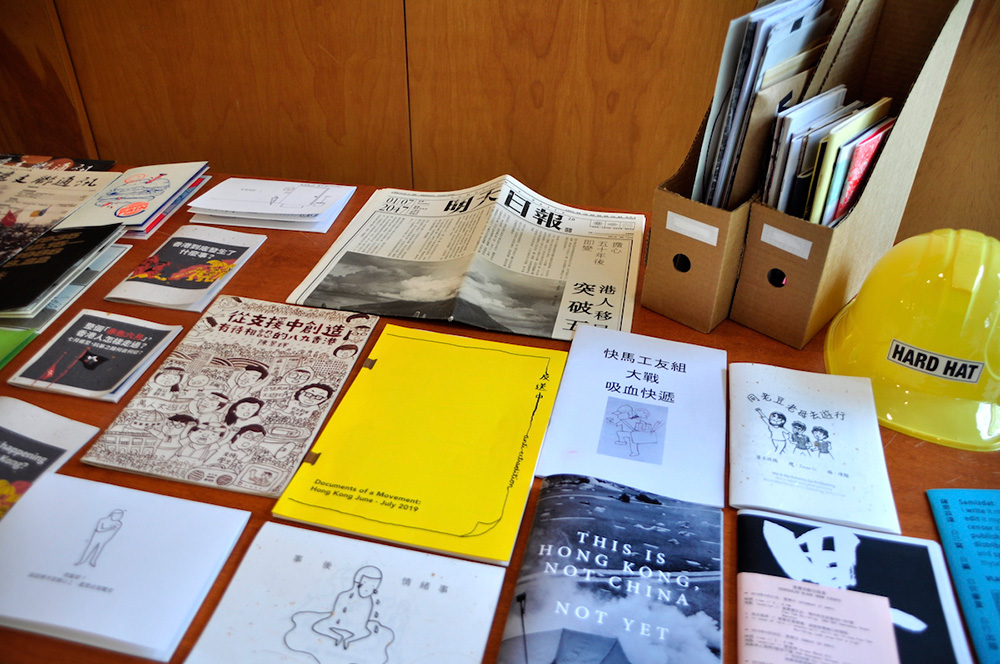

What is each of your favourite zines or printed matter in the exhibit? You can go get it right now and show me if you want!

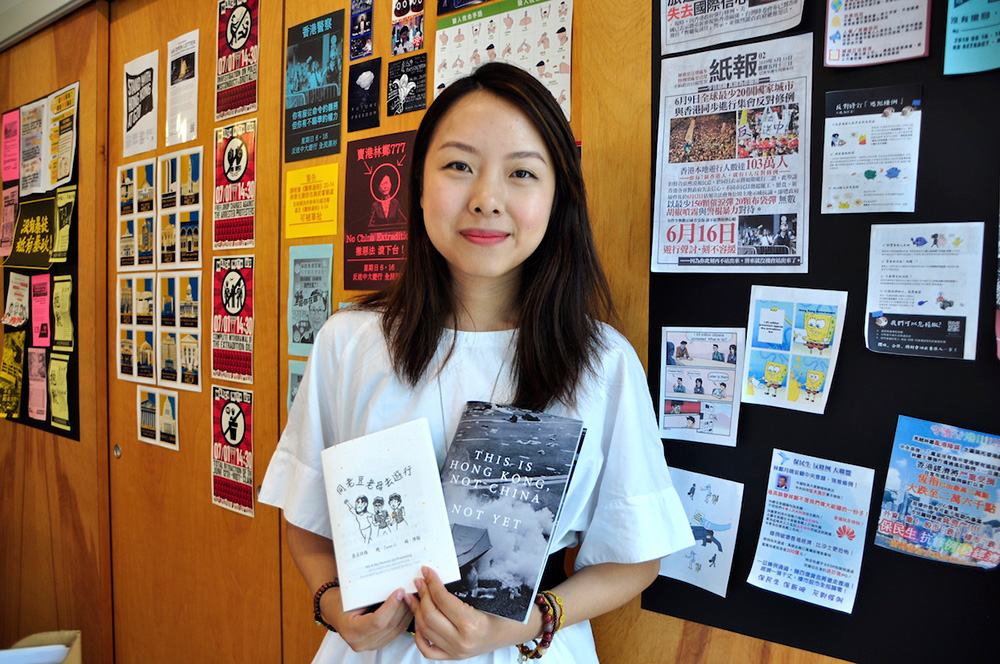

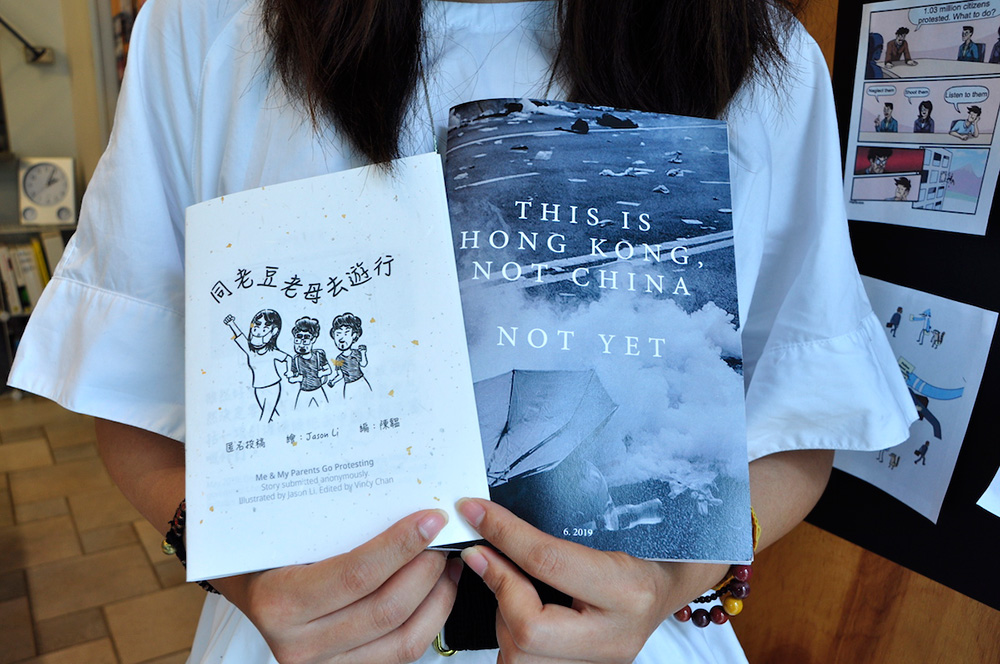

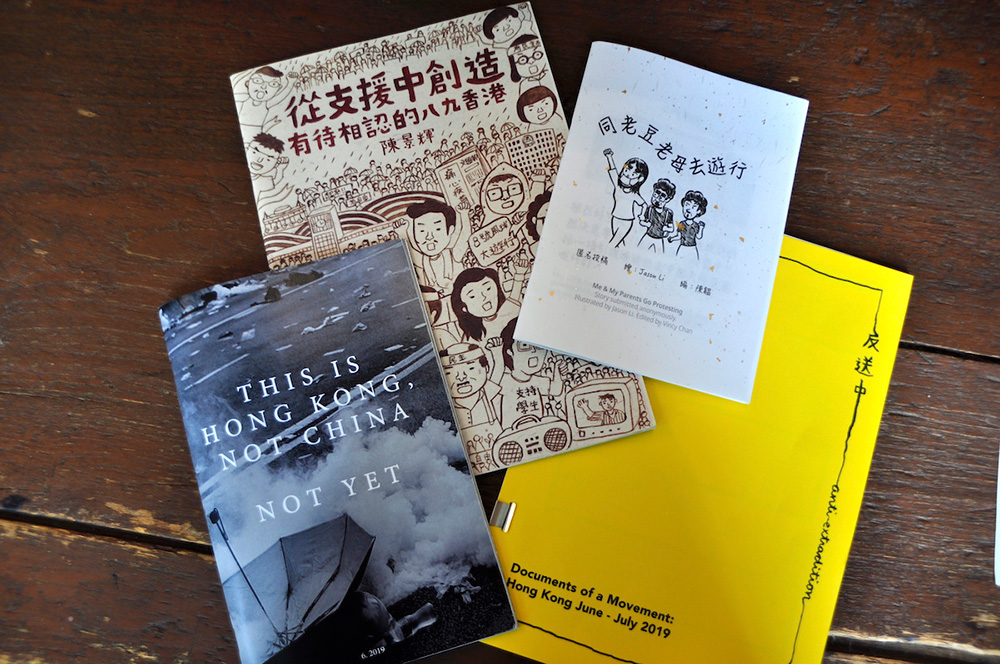

Ng: In terms of the ones I like, there are many. But the most memorable one is this one. [Ng picks up This is Hong Kong, Not China. Not Yet.] This one I talked about on CBC and in the Vancouver Sun because there’s this passage from an overseas Hong Kong person talking about their own experience of only being able to watch TV [to show solidarity]. That feeling of powerlessness. And when these things happen and you’re not in Hong Kong... that kind of guiltiness is like “Should I return right away?” But if you go back how long can you stay? How many times can you return? You don’t know how long this movement will carry on, but you keep asking yourself, “What can I do?”

I cried when I read this on the day I received it. This is the most memorable and profound item so far. Another one is by a collection of artists who collected everything then published it. It’s also an anonymously sourced publication. It has images from protests of their own design, or printed matter, and everyone’s encouraging words.

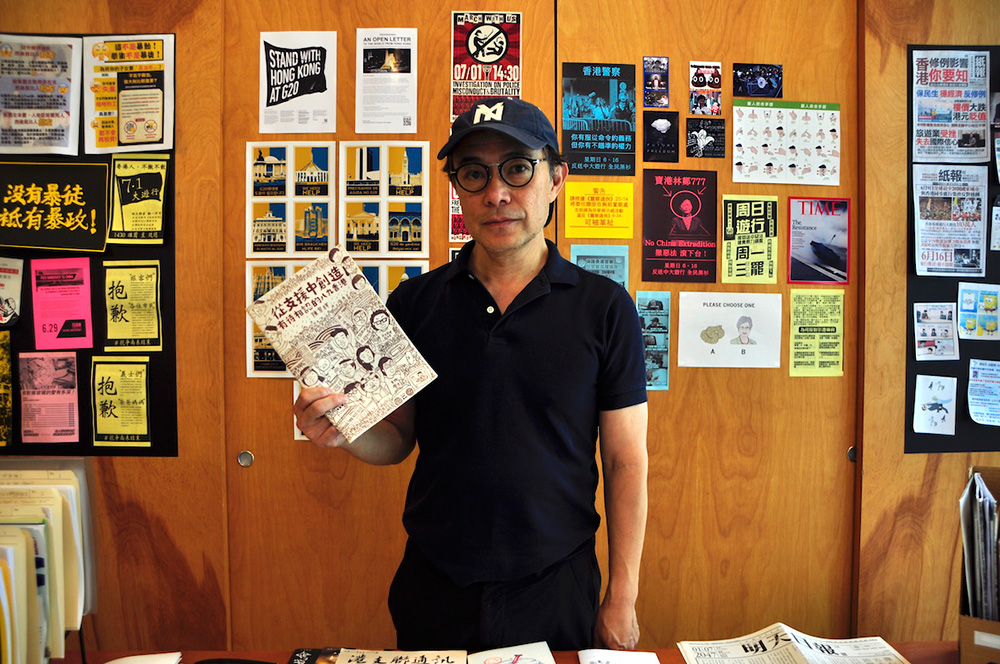

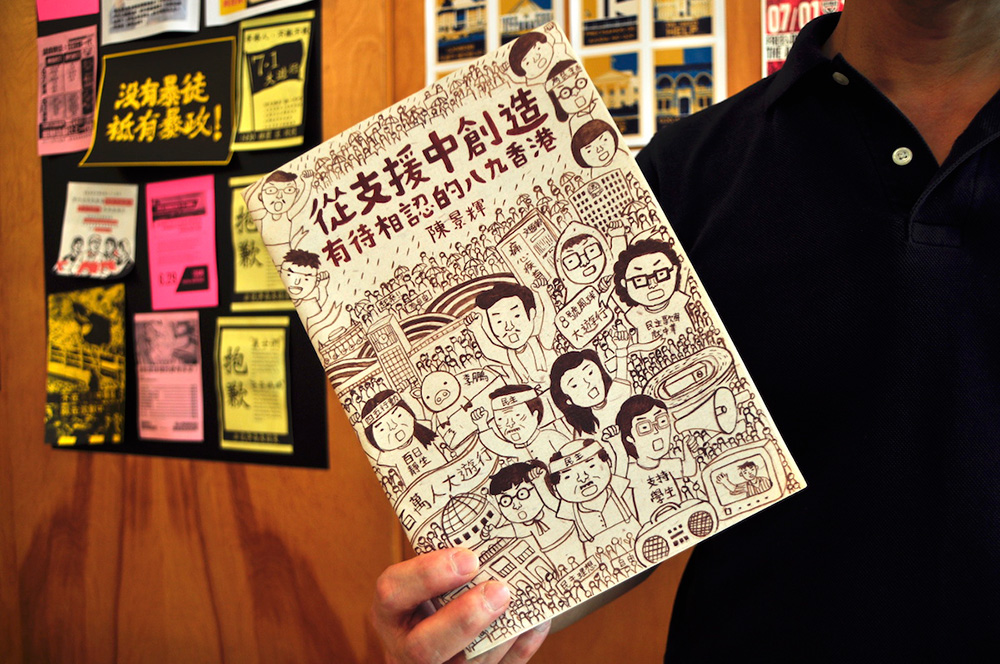

Tam: Personally I like this one called 從支持中創造有侍相認的八九香港 (Through Support We Contribute — The Unrecognized 89HK). I really like the art and text that bring it together to contextualize everything. There’s a very detailed history, but at the same time it’s very personal because the artist tells you about himself and how he came to understand the civil movement. It’s not really directly about what is happening right now. But I guess it’s a good overall view of the artist, of how people feel or felt during that time in Hong Kong. And the art is amazing.

Ng: This time around a lot of audience members, they’ll also ask about the issue of conflicting political views between two generations. Like your dad and mom are pro-police, pro-CCP, but you, as a so-called Yellow Ribbon who supports protests, or more neutral, how do you face that kind of conflict? I highly recommend this book [referring to 同老豆老母去遊行 (Me and My Parents Go Protesting)]. Someone submitted this story anonymously to Jason Li and then he helped to illustrate while Vincy Chan helped to translate it. This is a softer approach to ease some of the tension. And this really explores a concern about “are we just not going to talk or are we going to argue and fight? We’re family after all.”

Can you tell me more about the way that culture and humour was incorporated into the printed matter that came from these demonstrations and protests?

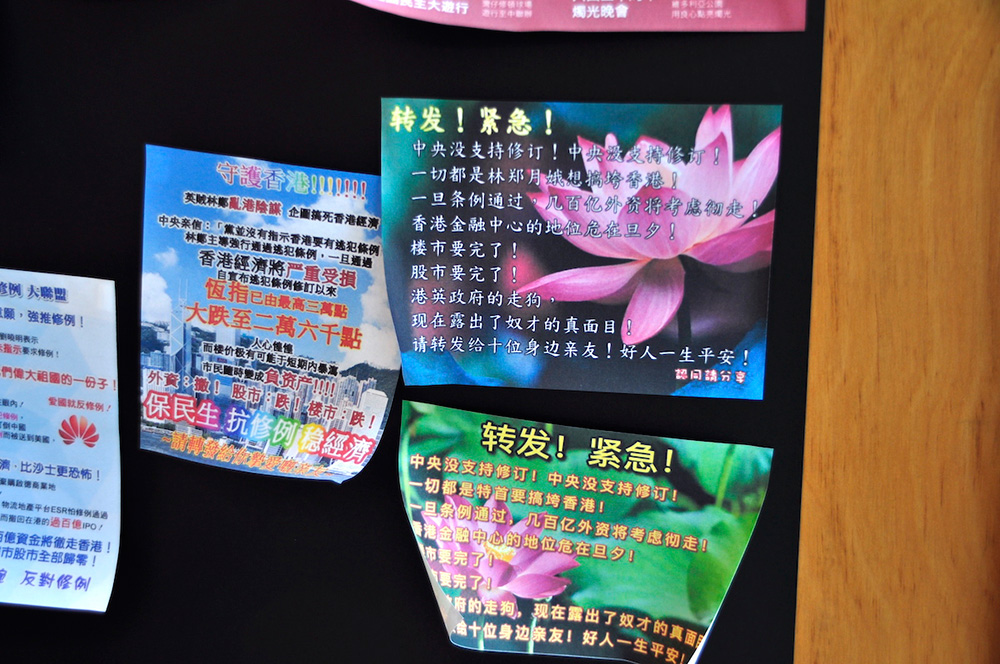

Ng: Like I was saying earlier, in the past the end product was a sheet of paper or a leaflet of sorts. But this time you can see the culture people will use, these “senior memes,” because they know it’s not easy to reason with this older generation or a positive debate is not very effective. Rather, it’s better to use a softer approach, using an appealing graphic sense to create these promotional materials. These “memes” might not say "返送中" (“Anti-Extradition to China,”) but they will talk about something they’re concerned about, like “Your money will become waste paper. Your property will depreciate. You need to come out and support this cause!” There is a kind of performance there.

Tam: Do you think it works?

Ng: Yeah, I think so!

Tam: To me it seems like the people were using the way people would read the message and you sneak in [these] kind of subversive statements to make them think, and I thought it was very clever.

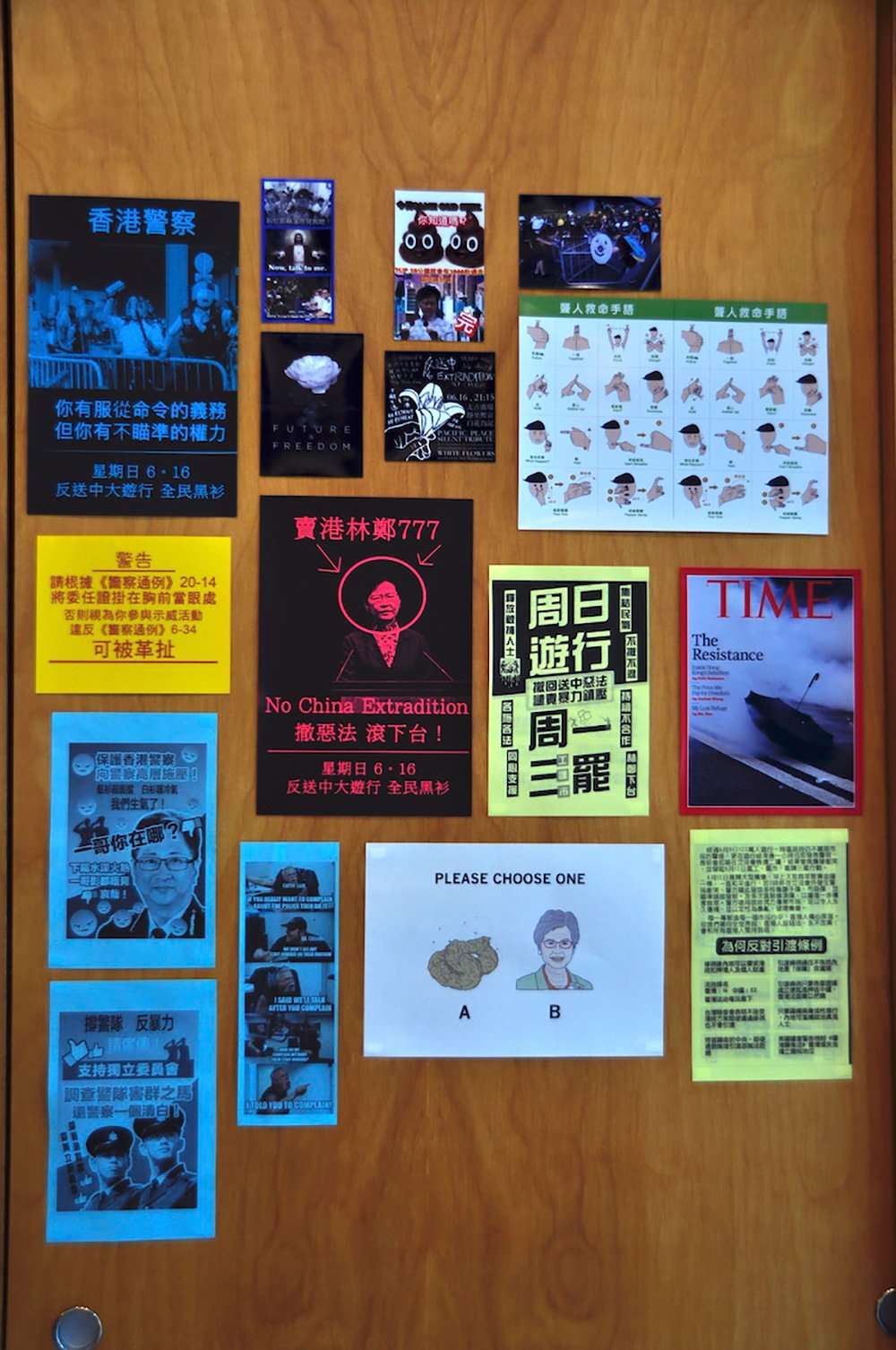

Ng: There are a couple more things that I quite like. Other than putting up posters on site, this time there is a mobile “打小人." [Villain hitting; a kind of folk religious practice where usually older women perform a ritual which includes hitting the photo of the “villain” with a shoe.] They will print the faces of all the politicians and post them on a wall and then hang a slipper there and you can hit them. Another thing is Democratic Dance Machine, where they will print out their faces and stick them to the ground like the layout that we used to use on the dance machine. There is another thing that’s a warning sign that police are required to show their badges, or they violate their own policies. In the photos I saw someone hanging one of these warning signs from their neck in case there is any kind of confrontation. It’s a kind of a reminder for the police.

This time someone made stickers. I mean there usually are stickers, but this time I really like these stickers that were created to look like “符” [a Taoist paper charm]. I think these are all quite interesting. Like the dance machine. There’s no way we could move the dance machine outdoors, so we recreate it using print. It’s really quite a humorous transformation. It’s also a venting of sorts. Oh there’s also a hopscotch! So there’s a lot of these things from our collective memory that were recreated through print.

They’re taking culturally specific rituals or memories and then applying them to the social situation using printed matter as a setup or installation.

Ng: Foreigners might not understand it, but for us Hong Kong people, we think it’s hilarious. Or there’s some really hilarious things like our Chinese tea houses, they created a menu for cops called the “Police Gang’s Happy Meal.” Regardless of the setup or the graphic sense, it echoes a lot of Hong Kong’s culture.

Why do you think Hong Kong people have this kind of sensibility?

Ng: Because we’ve tried everything.

Tam: I think it’s actually universal. Because I come from a different generation, I remember when there was the Act Up! movement against the AIDS crisis. People at the protests were very angry, but at the same time they were using a lot of really unthinkable tactics to ridicule the situation. They would bring a coffin and the dead people’s ashes would be in it, and they would just bring it to the White House and dump it on the lawn, or things like that. I think they used a lot of creative ways to get the message out.

Maybe because a lot of artists or creative people are also involved, they have these outrageous ideas to express themselves and how they feel.

What are you hoping that viewers will walk away with from seeing all the printed matter here? What are you hoping they’ll get from this?

Tam: Well so far I’m just hoping I could bring in some variety of audiences.... That’s my hope: to bring in more understanding of the politics in Hong Kong right now. To let them see a different point of view, hopefully. I think a lot of Canadians or people from outside are sided with the protesters. That’s how I feel. But you never know. Because sometimes I go online and then I see my good friends online, [and] they were supporting the police or government.

Ng: What I want the audience to take away is that the next time you want to say something, you can use this method. It’s quite diverse. You don’t need to feel a huge amount of pressure that you must be an artist or a graphic designer to do it. You can see a lot of things; you can just handwrite it and then photocopy it.

They will know that you can use this method to influence others. It’s really easy to do. And it won’t take a lot of time or money. Most important is the message it contains. The reason there are so many kinds of graphic styles on display is because we want to speak to the diverse voices and diverse ways of expression.

Maybe within the resistance there are some who go out and show up, others who donate money, and doing print is another way of participating. And within doing print, making leaflets is one way, stickers is another way, zines is another way, so maybe this can be an inspiration for everyone.

So responding to the topic of Freedom-Hi!, we are using every way we can to see if we have the chance of meeting freedom, to say “hello.” This is all related to freedom of expression, freedom of the press and freedom of speech. We can see the police are not only targeting protesters, they’re also targeting journalists. This is a terrifying thing — attacking the freedom of the press. This is not just us, but this is related to the entire system’s informational transparency or correctness, and neutrality. This needs to be protected.

'Freedom-Hi!: Zines from Hong Kong's Civil Movements' runs at Hotam Press Bookshop and Gallery, 218 East 4th Ave., until Saturday. Find the event here. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: