- Ted Grant: Sixty Years of Legendary Photojournalism

- Heritage House (2014)

Dean Norris-Jones has invited the father of Canadian photojournalism to speak to his Grade 10 photography students at Reynolds Secondary School in Saanich every year for the past 30 years.

Ted Grant usually presents for an hour, and then Norris-Jones shows Ted Grant: The Art of Observation, a documentary about Grant's life and work. The following semester, once the kids have absorbed a great deal about Grant's 60-year career, Norris-Jones invites Grant back to the class for a dynamic Q&A session.

As he introduces Grant to his 2012 class, Norris-Jones tells the students: ''Whether you have been aware of it or not, Dr. Grant has had an indelible link to your mind's eye.''

Grant begins his talk by asking how many students have cameras on them, and only four or five hands go up. Grant reminds them that they live on Vancouver Island, and when the big earthquake hits they'll need cameras to take the pictures they will be well positioned to sell afterwards.

Lesson one: If you are a serious photojournalist, always have your camera ready and anticipate opportunities.

"Taking pictures offers you the coolest life you can imagine," Grant says. "You are constantly alive with seeing the world differently. Photojournalism has taken me around the world. It gave me a magical career."

With that introduction, the teenage boy in the front row digging into a footlong Subway sandwich puts it down. The unwrapped sub sits on the desk for the entire time Grant is speaking. Forty non-texting 16-year-olds sit attentively for the duration of the octogenarian's presentation.

'It isn't the camera'

The point of Grant's first slide -- ''It isn't the camera; it's the holder'' -- offers the tech-savvy students something to ponder. ''I am a photographer, not a technician,'' Grant declares. "When we focus on pixels and technology, we risk losing the photography impact moment.''

Grant uses the podium opportunity as a chance to spread some of his own personal gospel. He tells the students that the glory stories about war did not reflect his experience as a war correspondent. He remembers the photojournalists and reporters killed in war zones all too well.

"I don't hear that well these days. I got my ears blown out as a photojournalist during the Arab-Israeli War. And by the way, don't sign up to be a war correspondent. It isn't remotely glamorous. You could be in the wrong place at the wrong time. And the reason for being there is usually about sheer stupidity," he says.

His advice? "If you really want to see something exciting, go up to northern Canada and photograph the polar bears. Or stay home and take pictures of the garden -- and that can be extremely challenging, by the way -- right in your own backyard."

Next, Grant advises the students to dress appropriately for each assignment. At this point, he leans toward Norris-Jones and asks, ''Can I say 'rat-assed' in here?'' With the teacher's nod, he continues.

"Sometimes photographers look like a bunch of rat-assed bums. If you are at a G8 Summit with world leaders or dealing with a CEO who is wearing an expensive suit and shoes that cost who-knows-how-much, you don't want to look as though you were just shot out of a cannon sideways. How you dress and how you speak to people will determine your future assignment offers."

He goes on to tell the students they need to learn to work from the heart and learn everything they can about lighting. He talks to them about Rembrandt. He talks to them about the 150 or so births and surgeries he has attended and photographed. Behind each image is a good yarn and a well-emphasized point.

Grant gets the students to start thinking about their own possibilities. He mentions that his grandson took a photography course but is making more money delivering pizzas. He lets them know that photography is a tough way to make a living right now. With that understood, he carries on.

"Go up to Mount Tolmie and park your butt on a bench before sunrise. Watch the east and ask yourself, 'What is the light doing to what I am watching?' You'll learn that you don't need to use flash. Flash is disturbing in most situations, and when you don't use it, people are less aware of what you are shooting. Flashes can often destroy what motivated you in the first place."

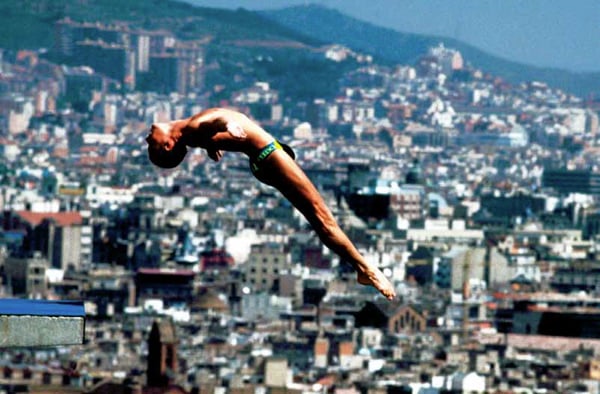

He tells more stories. He shows his stunning picture of a diver at the 1992 Barcelona Olympic Games.

"This is so easy, you are not going to believe it. Here is the tip of the diving board at the far left of the picture. Use it to focus the camera. And then you wait. The diver leaps in the air, and you go click. If you focus on the diving board, you have the shot. Click. And then you go for a beer."

'He helped me'

At the end of the lecture, Grant shows the picture of himself upside down in a fighter plane (this story's cover photo). The kids initially laugh at the upside-down image until they realize it is not a mistake, and that this guy, who is easily old enough to be their great-grandfather, actually flew upside down in a Mustang P-51 fighter plane to celebrate his 76th birthday and photographed himself doing it. A noisy round of applause ends the class and several students linger to ask Grant questions.

Dean Myhal, who has been shooting as a hobby for five or six years and is currently taking photos for the Canadian Geographic Photo Club, quietly asks for Grant's autograph. He hopes to eventually get some work as a photographer.

''It's really cool to meet Ted,'' Myhal says, ''I was excited about him being with us for this class. I have seen a lot of the pictures he showed us today but never knew they were his. The whole presentation was great, but his explanation about taking pictures from the shadow side was especially interesting to me.''

Counting Norris-Jones's students alone, Grant has influenced more than 1,000 young photographers over several generations in Victoria, B.C. over the last 30 years, and has given other talks across North America. After he presents, he tries to make time to chat one-on-one with as many people as he can. ''I have always made a point of that because sometimes people might be a little reluctant to ask questions in front of a group,'' he says.

At 85, Grant has added substantially to the mythology of Canada with work that will never age -- namely, more than 300,000 images in the national archives in Ottawa are his. He jokes that he expects to live to 100 and plans to be buried with a camera and offers this reflection on the kind of legacy he hopes to leave:

"I would like to leave a legacy where I was seen as a motivator and an inspirer of both amateurs and professionals. I would hope they might have learned something from a class I gave or from observing some of my work. I would like people to say: 'He helped me.'

"I have always felt that you get what you give in life. If you are working with someone and their camera breaks or stops functioning and you lend them a camera -- the legacy you leave is that they remember you helped them, even if you were competitors."

Excerpted and republished here with permission from Ted Grant: Sixty Years of Legendary Photojournalism by Thelma Fayle, Heritage House, U.S. release 2014. This version has been lightly edited for clarity.

Please note our comment threads will be closed Dec. 22 to Jan. 5 to give our moderators a well-deserved break. Happy holidays, readers. ![]()

Read more: Education