Jorge Luis Borges, the blind Argentine, always hoped that "paradise will be a kind of library," a sort of literary labyrinth where unsettling characters and ideas could happily collide like storied travelers at an airport.

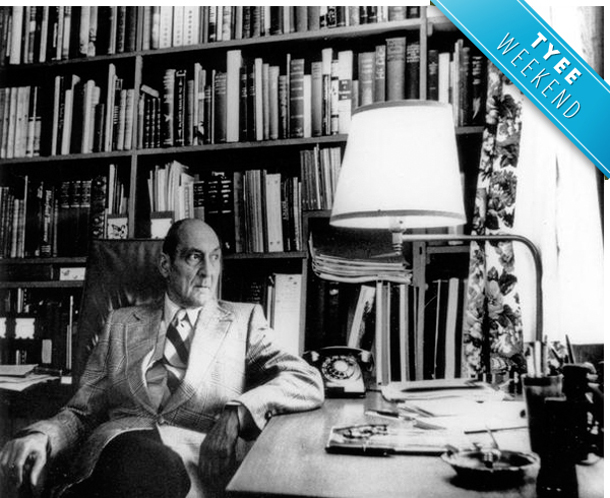

In the 1950s the celebrated writer and conservationist Roderick Haig-Brown and his wife Ann, a school librarian and fiery Catholic, built one such wordy paradise in their home by the Campbell River on Vancouver Island.

At the time Campbell River was known for its industrial logging and wild salmon fishing, and Haig-Brown, the local magistrate, had just published Measure of the Year.

(This brilliant reflection on love, family, rivers and justice remains one of Canada's finest and most rewarding pieces of non-fiction.)

Haig-Brown, who was an early and largely unrecognized Canadian version of the renowned U.S. writer Wendell Berry, thought that if you liked reading books, "a library begins to happen to you."

Well, one happened to Roderick and Ann, lovers of books. Their collection eventually grew into a special room with ceiling-high shelves containing 3,000 volumes in red, green and gold colours. Paisley drapes and a fireplace bedecked with a wooden orca carving by Sam Henderson just added to the decor.

There, too, is a pipe rack on Haig-Brown's desk, and lots of fly fishing gear. (Roderick wrote about fishing the way William Blake wrote about God.)

Over the years the library kept on happening even after Roderick died of a heart attack in 1976. Its growth came to a halt with Ann's passing in 1990. Yet its lively contents continue to enrich any humble reader, the way a cold river nourishes young salmon.

Browsing through the remarkable collection (everything from Kipling to Plutarch) is a bit like fishing. You never know if you'll catch anything as worthy as wisdom, experience or even a long-lost feeling. Haig-Brown knew that only a rare book (and a rare fish) could change a life, and that a poor one added nothing to it.

In any case no respectable fisherman, except those with economic degrees, would ever describe a fish-less afternoon as ill spent. A good library, much like the flow of a river, suspends time and invites the idle wader to subversively reflect on lives fully lived, or engage in "gentle study without excessive purpose."

This probably explains why high-tech industrial societies hold no more respect for libraries than they do rivers. Memories, not shaped by machines, remain dangerous freedoms.

Last winter I had the privilege to serve as the writer in residence at the Haig-Brown house. The library, now lovingly managed by Museum At Campbell River, called to me on a regular basis, and I often disappeared at all hours of the day and night to go book fishing.

From 'Berlin Diaries' to 'The Wild North Land'

Some of my illuminating and random catches suggest, as Haig-Brown put it in his truly beautiful Measure of the Year, that a good library "resembles a deep pool in a river, whose depths move slowly."

In these depths I first grabbed an original copy of William Shirer's Berlin Diaries (Alfred Knopf, 1942).

Stationed in Hitler's Germany between 1934 and 1941 the famous CBS correspondent watched, in disbelief, as the middle class drank the poison of fascist propaganda and became hostages to moral cowardice.

The Nazis, much like contemporary governments today, even asked the correspondent to "report on affairs in Germany without attempting to interpret them."

Berlin Diaries reveals all the sordid going-ons that German censors wouldn't allow Shirer to put on radio. Tellingly, much of the book chronicles the relentless and industrial abuse of language.

Before trashing most of Europe, the Nazis cleverly declared, for example, that "we want peace with equal rights and security for all." And when the Germans invaded Poland, Hitler's wordsmiths called it a "counter attack."

Words "had no meaning for" Hitler reported Shirer, and I suspect they have not much meaning for Harper or Putin either.

A good cast away from Berlin Diaries, I found a dusty old copy of The Wild North Land by William Francis Butler (Porter and Coates, 1874).

Written after The Great Lone Land (another neglected Canadian classic), this volume breathed frost, Cree and aspens.

From 1872 to 1873, the soldier (a Canadian version of Lewis and Clark combined into one damn Irishman) took a long northern walk from Fort Garry (Manitoba) to Fort Chipewyan and then on to Quesnel, British Columbia.

As Butler walked, he noticed that civilization or what passes for it (the machine-made boot and two cent newspaper) "rolls with queer strides across the American continent."

At the Forks of the Athabasca River, then a global outpost for the fur trade, Butler and his party stopped to refresh themselves one cold March with tea, cakes, sweet pemmican, moose steaks, salmon and even peaches and pears.

Ironically, Butler paid for the trip by selling oil-rich land near Petrolia, Ontario. During his walkabout, the captain spotted the black resource that would later transform Canada's character so irrevocably 140 years later: "From bank to bank fully six hundred yards of snow lay spread over the rough frozen surface: and at times, where the prairie plateau approached the river's edge, black bitumen oozed out of the clayey bank, and the scent of tar was strong upon the frosty air."

From Epictetus to Bill Reid

Another night my hand landed on the The Discourses of Epictetus translated by a George Long (A.L Burt Company Home Library Collection, 1877). The great Greek slave philosopher seems more relevant with the passing of every day. A library without Epictetus is a B.C. river without trout.

While browsing the slave's anti-materialist discourses, my eye spotted this salient advice -- and what mortgage slave has not sweated this thought?

"As you would not choose to sail in a large and decorated and gold-laden ship (or ship ornamented with gold), and to be drowned; so do not choose to dwell in a large and costly house and to be disturbed by cares."

(It seems that the ancients preferred philosophers who lived in shanties while the people of petroleum only trust moral guides who live in mansions.)

Epictetus also knowingly wrote, that "Every place is safe to him who lives with justice."

There was more. Shelves of books above Haig-Brown's desk offered a rich variety of titles on nature, ecology and animals including Duck Shooting, The Secrets of the Eagle and the original 12-volume edition of the Fur, Feather and Fin Series.

But it was a 1948 copy of The Plundered Earth that landed on my lap.

Henry Fairfield Osborn, the president of the New York Zoological Society and a wealthy racist to boot (his uncle was J.P. Morgan), declared more than 56 years ago that humans had royally fucked up: they "had become such an earth changing force that they had completely disrupted the symphony of Nature."

He didn't view technology as a saviour either. "Technologists may outdo themselves in the creation of artificial substitutes for natural subsistence -- but they cannot offset the present terrific attack upon the natural life-giving elements of the earth."

Osborn offered one solution, and it is the one that no environmental group or government really champions: Mankind "must temper his demand and use and conserve the natural living resources of this earth in a manner that alone can provide for the continuation of civilization."

Haig-Brown often lamented our careless spending of resources too. Underneath a wood table, I found a large, two-foot-long binder with an engraving by the artist Bill Reid. The binder contained a collection of fine fish prints as well as a beautiful copy of The Salmon by Haig-Brown, who wrote more than 25 books.

The Fisheries and Marine Services of Environment Canada published the book in 1974 when, oddly enough, the federal government still feigned more interest in natural wealth (salmon) than in pipelines.

"If weakness and indecision allow the salmons, in their abundance, to disappear from the rivers and the oceans, what hope can there be for the future of life itself?" asked Haig-Brown.

From Hochbaum to Anonymous

Tellingly, Haig-Brown, arguably one of Canada's greatest conservationists, kept in his library two books by his equal and peer: H. Albert Hochbaum, Canada's other great naturalist. It was Hochbaum's visions of a land ethic that greatly shaped and influenced the writings of Aldo Leopold.

Hochbaum, a large and gentle man, lived in Delta Marsh just north of Winnipeg and studied waterfowl most of his life. He wrote about ducks the way Haig-Brown wrote about fish. Hochbaum's classic, The Canvasback on a Prairie Marsh (American Wildlife Institute, 1944) swims on the same shelf as Travels and Traditions of Waterfowl (University of Minnesota, 1955).

Hochbaum, who genuinely loved people, wrote urgently about the need to conserve wetlands because he felt that ecosystems, like the prairies, desperately needed kidneys too. Wheat salesmen and barley economists ignored him.

"The time when we start saving the prairie marshes may arrive when we somehow realize that we need these wetlands for our own human race, when we understand that the real concern is not for the ducks, but for the people themselves; Can we continue to be strong and healthy on this North America after we have let the gems of upland waters drain to the valleys?"

Given Haig-Brown's passion for salmon and trout, a special wall of the library singularly offers only titles on fish or fishing. They bear lively titles such as Grim: The Story of a Pike and Any Luck? Right next to Trout Fishing From All Angles sits my favourite: The Rod in India (Being Hints How to Obtain Sport) by a very jaunty Henry Sullivan Thomas (W. Thacker and Co, 1897).

Fishing in the colony, which included hooking 100-pound carp (and apparently you needed a servant to help land the damn thing), required some imperial nerve: "The rain is one hindrance, muddy water another, fever, etc, a good third."

And then there is Songs for Fishermen by Joseph Morris and St. Clair Adams. Published in 1922, the book contains just about every poem and song ever written about fishing.

Many of the best ditties, such as "The First Worm," are by that ever-prolific poet, Anonymous:

"This morning as I went to work

"(For work I was not wishing),

"A worm crawled briskly out and said:

"'Come on, let's go a-fishing.'"

Inside this treasure of a book rested a handwritten card by Haig-Brown himself that contained another anonymous poem: "The Fisherman's Lament":

"Sometimes too early, Sometimes too late, Sometimes no water, Sometimes in spate, Sometimes too dirty, Sometimes too dear, There's always something wrong, When I'm fishing here."

But no reader could ever make such a lament in the Haig-Brown library.

Here, the fishing miraculously improves with age because libraries, like a well-told story, never grow old. ![]()

Read more: Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: