[Editor's note: The following interview with Stan Douglas by art historian Alexander Alberro is excerpted with permission from Stan Douglas: Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971, published this month by Arsenal Pulp Press. This collection of essays pries open the iconic 30x50-foot translucent photo mural, depicting a decades-ago clash between police and protestors that defined Vancouver's Gastown neighbourhood, and which now hangs in the atrium of the city's Woodward's complex. From Nora M. Alter's analysis of the image as a "moving still" to Jesse Proudfoot's history of the politics of representation in the Downtown Eastside, these essays help fulfil Douglas's intent to keep conversation about the riot -- and the photograph that "condenses" it -- evolving. Enjoy.]

Alexander Alberro: What is the event that your photo mural Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 represents?

Stan Douglas: It all began as a "smoke-in" at Maple Tree Square in Vancouver's Gastown district, organized by the Georgia Straight, the local alternative newspaper. Bands were invited to play music; flowers, popcorn and watermelon were given away; and at one point a ten-foot papier-mâché joint was paraded around. It was a typical early 1970s hippie festival. Thousands of people came to take part, and by all accounts were having a peaceful time until 10 p.m. when the police arrived and told them to disperse. There were so many people that few heard the (police) chief declare over a megaphone that they had ten minutes to clear out, so few did anything. It seems that there were a couple of agendas on the part of the police force. Undercover narcotics officers dressed as hippies had mixed with the crowd, seeking to identify drug dealers and what they called "troublemakers." Their aim was to detain these people, to arrest them. Other officers were instructed to clear the streets, which is what they tried to do. This made it difficult for the narcs and for those from the mounted squad, who were trying make people stay put until the paddy wagons arrived. Not surprisingly, the police vans were delayed by the whole street-clearing effort.

When the police charged, people couldn't run north because of the waterfront; they couldn't run east because that's where the cops were; and they couldn't go west because that's where off-duty officers had assembled and had begun to march into the fray (you see them in the upper right-hand corner of the picture wearing white helmets). So when people tried to disperse in the directions we see in the picture -- west and south -- they were trapped by one segment or another of the police force, and the confusion on the part of the cops precipitated the confusion and panic of the whole event.

AA: So the corner that the Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 mural depicts is on the margins of the epicentre of the event?

SD: Exactly, yes. The corner of Abbott and Cordova is one block away from the epicentre. But of course the event became dispersed almost immediately. When the riot squad moved in, everyone began to run. Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 depicts one of what must have been many micro-events around Gastown that night.

AA: The 21st century has begun with a lot of street demonstrations that have resulted in clashes with the police. To what extent is your decision to focus on the events of Aug. 7, 1971 driven by these contemporary events?

SD: I consider the demonstrations against budget cuts that we're seeing in Europe today, or those against the formation of the World Trade Organization a decade ago, or those against the Iraq War in 2003, to be much more serious than what's depicted in Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971. Relatively speaking, the coming together of people in August of 1971 was a frivolous protest -- I mean, protesting the fact that they weren't allowed to smoke pot.

But in a larger sense, what the protest was about was the curtailment of civil liberties. And I think that the large gathering in Gastown that day, as light-minded as it might appear now, was enabled by the large antiwar and civil-rights demonstrations of the 1960s. So just as the events that I've rendered are at the periphery of the epicentre of the riot, the event as a whole was at the periphery of, but nonetheless related to, the mass demonstrations of the 1960s and early 1970s.

AA: How did the project initially come about?

SD: The conversation was initiated by the architect Gregory Henriquez. He asked if I was interested in doing a work for a project he was designing in North Vancouver. I told him that I would be more interested in doing something for the commission he had in Gastown, at the old Woodward's department store site. Eventually I had discussions with him and the developer, Ian Gillespie, and to my surprise they were very enthusiastic about the idea of making a picture of a riot.

AA: Was the project very expensive?

SD: It was made like a motion picture, like one shot in a major motion picture on a purpose-built location. At first we wanted to work on the original site. But we soon realized that it would be a lot easier, and a lot less expensive, to build the location, which is what we did.

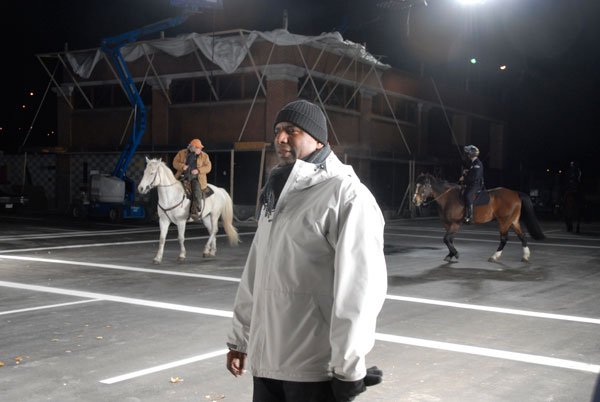

We rented a large parking lot beside the Hastings Park Race Track, laid blacktop for the streets, poured concrete for the sidewalks, installed flats for the two buildings, and then aged everything. We waited for the production of The Day the Earth Stood Still to wrap so we could get all the lighting we needed from Paramount Pictures. Freezing the action of people and horses running about an intersection without too much motion blur at the optimal ISO and aperture required 700,000 watts of tungsten light.

Casting performers was a long process. I looked at more than 1,000 head shots and one-sheets, which I organized into groups and categories of people who lived in the area. Then everyone had to be fitted for period costumes, and the performers had to be styled and made-up.

The whole thing was shot over three nights. The nearest part of the scene was shot on the first night, and Abbott Street and beyond on the second. We shot the plates, or backgrounds, on the final night. I devised nine scenes, or general groupings of performers and their interactions, for the first two nights, but of course improvised and modified my direction based on what was happening.

The picture is composed of about 50 discrete images composited together. At first I thought I could shoot the piece on 4x5 or 8x10 film, and even had a scheme to keep a processing lab open while we were shooting. But after doing some side-by-side comparisons with high-resolution digital backs and lenses, I realized that if I shot digitally there would be less chromatic aberration and better geometric stability. I would also be able to see the frames immediately. I wouldn't have been able to make this photograph as well, or as quickly, using analogue means, and I've shot digitally ever since.

AA: Why did you decide that the elevated shot, the elevated placement of the camera, would be the most appropriate for this image?

SD: As the idea of making a picture of a riot was coming together, I began to look for some kind of model or precedent, a paradigmatic image. I briefly became fixated on a photo of the famous Battle of Cable Street that took place in London in 1936. It represents a clash between the Metropolitan Police, overseeing a march by the British Union of Fascists and anti-fascist groups. But let's not read too much into that. I just liked the way the photo depicted crowd behaviour. At that point I still thought we could work on location and get away with installing a single flat of the Woodward's building.

But when it became clear that we were going to build the entire intersection, I started to explore other vantage points and decided to look southwest, toward the corner of the department store.

We made a 3-D model of the location to pre-visualize what the set would look like, and to know what would have to be built. My producer, Arvi Liimatainen, informed me that we couldn't afford to duplicate the Cable Street view because it looked too far down the street. At that moment, the camera was positioned at what would have been a second floor window of the Travellers' Hotel, one of the places where hippies had begun to hang out. I kind of liked that, so I just panned a little to the left and the problem was solved.

AA: Clearly Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 also establishes a relationship with advertising.

SD: Certainly. The piece takes the format of a large billboard advertisement, or public service message, close in scale to the huge Kodak backlit transparency that used to hang in New York's Times Square. But it doesn't play by the rules of advertising because it presents content that is obviously non-commercial. Insofar as it disrupts the conventions of a medium with foreign content, the work relates to my earlier Television Spots (1988) and Monodramas (1991), in which narrative content that one would never normally see during an advertising break was inserted into the flow of broadcast. Abbott & Cordova doesn't present a pictorial gestalt typical of billboards, one that can be read quickly from, say, a passing car. Rather, it's meant to be read in bits and pieces because the architecture of the complex very often reveals the image in fragments as one rounds a corner or approaches it from the street.

AA: What's at stake for you in this particular event? Do you remember it taking place?

SD: No, not really. I don't recall the event. I wasn't there. I only knew about it from hearsay and, I suppose, from a drawing by Vancouver artist Neil Wedman called Gastown Riot (1998), which has a completely different take on the riot. I never got into it in depth until I began to do some research. But keep in mind that I've been loitering in this neighbourhood for most of my adult life. I've rented studios in and around Gastown, and frequented shops and bars here for years. Today my studio is three blocks east of Abbott and Cordova. So I've been in the neighbourhood for quite some time, watching its decline, and recently, the slow process of its gentrification.

AA: The 100-block of West Hastings, featured in your panoramic photograph Every Building on 100 West Hastings from 2001, is just around the corner, isn't it?

SD: Yes it is, it's just one block south of Abbott and Cordova. I think that's part of what got Gregory (Henriquez) interested in inviting me to do something. The 100 West Hastings photograph depicts the neighbourhood as it was left to go fallow until it became commercially exploitable again. You might also want to note that the 2001 photograph looks at the block from the point of view of the building where the mural now stands. And, in a way, 100 West Hastings shows the effects of the event that's being depicted in Abbott & Cordova.

AA: What do you mean?

SD: Well, the key thing about the riot is that it changed the character of the Downtown Eastside for decades. In the 1970s, Vancouver mayor Tom Campbell initiated what he called "Operation Dustpan," a plan of police action to sweep away "filth" -- i.e., hippies -- from the streets. Hippie Central was in the west-side Vancouver neighbourhood of Kitsilano. The mayor thought that the things the hippies were doing there were immoral and often illegal but somewhat contained, which enabled the city to police them. When the hippies began to move downtown, squatting in old commercial and industrial buildings in Gastown and mingling with the locals, the police started to arrest or harass them with claims that they were selling drugs.

But after the 1971 riot, new zoning regulations made residential occupancy impossible. The Woodward's department store had always been the retail centre of the city for lower-middle and working-class people who couldn't afford to shop at more uptown establishments. But then shopping malls began to open in the suburbs, and Gastown became almost exclusively a tourist zone, buzzing during the day but desolate at night since there wasn't a mix of local residents with a personal investment in the neighbourhood or in the surrounding area. Woodward's was bound to fail under these conditions, and closed its doors for good in 1993.

AA: Did you conduct a lot of research prior to setting out to re-stage the event?

SD: Yes, I hired a researcher, Faith Moosang, who dug up news clippings, photographs, and hand-written affidavits of the arrested, as well as civic policy memos and reports. She also did a series of interviews with a sample of those who were at the riot: police officers, shop owners and countercultural types. What the interviews revealed was just how terrified everyone was. For instance, the police, and the mounted squad in particular, had never been involved in anything like that before, and there was a general sense of panic on both sides.

AA: Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 is one of the four large digital C-prints that comprise your Crowds & Riots series. What led you to employ the loaded term of "riot," as opposed to, say, "uprising," when naming this series?

SD: Well, three of the four events depicted in the series are of "police riots," in which the very actions of the police generate the kind of violence that they are presumably meant to contain. But on another level, the four photographs represent the organization of people into a group or a body by either internal or external forces. The Free Speech Demonstration of 1912 is related to the efforts of the Wobblies (IWW) who came to Vancouver from the US in order to organize unemployed men. In response, the city outlawed public gatherings of more than a handful of people, as well as speech-making by all organizations other than the Salvation Army. The IWW agitators got around this by collaring people in alleys and making announcements by megaphone from boats in English Bay. They were able to get thousands of people to the Powell Street Grounds for a demonstration, which was ultimately broken up by cops wielding cudgels and bullwhips. Here, external agents tried to create a mass body.

The Battle of Ballantyne Pier took place in 1935 when about 1,000 unionized longshoremen, who had been dismissed and replaced because they had protested the way work was being allotted, set out to confront the scab labourers but were themselves intercepted by federal, provincial, civic and special police forces who engaged them in a three-hour struggle. In this case, a group of people identified themselves as a single body. The Hastings Park photograph represents people at the racetrack who, unbeknownst to them, have been made into a mass of consumers. The Gastown photograph depicts people who have coalesced as a group through their own shared values and camaraderie, but who have also been singled out as a group by the police. In the picture you can see middle-class people and working-class older men who watch the action as if it were street theatre. That's something I noticed in photographs and film footage from the time. People who couldn't be outwardly identified as hippies didn't feel threatened by the police action. They just watched as if it were some kind of entertainment.

AA: What kind of reception has Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 received?

SD: People seem to either love or hate it.

AA: How have the local police responded to the photograph?

SD: Funny you should ask. Two days before shooting, we got a call from the chief of police, or rather his executive assistant, summoning me to his office to explain what the hell I was doing. He added something to the effect of: "We've been trying to live this down for 35 years and now you want to make a mural out of it?" And the call probably came about because our horse wrangler, with our approval, contacted the mounted squad to ask if they still had any vintage tack. He also asked if any of them wanted to be in the picture. We naïvely thought that, 40 years after the fact, it was obvious that the riot-making police force of 1971, subject to and modified by an inquiry (the so-called Dohm Commission) the same year, wasn't the same force in place today. The 1971 inquiry sought to prevent this kind of riot from ever happening again, and resulted in changes in police policy. The police, after all, are civil servants, and are accountable to the public. But one of the many problems in the Downtown Eastside right now, the Woodward's complex included, is that certain areas are designated private property and patrolled by private security companies which, unlike the police force of 1971, are not answerable to citizens.

AA: You note that city regulations were changed after this event. Are all four events in the Crowds & Riots series pivotal in that sense?

SD: Yes, to a certain degree. But the earlier instances were moments of failure. The police were able to disperse the body created by the IWW in 1912, and the longshoremen who clashed with the police in 1935 failed to reclaim the status that they thought was their due. And of course the Hastings Park photograph is an image of a group of people in a moment of repose waiting for a horse race to take place so they can find out if they've made the right wager -- unaware of, or indifferent to, the fact that they've been produced as a group by the owners of the race track.

AA: So these four historical cases are moments of crux, of transition?

SD: Exactly, yes.

AA: What do the events of Aug. 7, 1971, signify today for Vancouverites?

SD: Well... my photograph.

AA: Are you suggesting that historical memory about at least this event has now become an image?

SD: I think so, yes. And I'm not being entirely facetious. The photograph has produced an image of something that could easily be forgotten; it consolidates hearsay into a picture that will hopefully produce more hearsay and a conversation about history -- as opposed to the way that, for instance, a sculpture of a general on horseback is supposed to do, but doesn't.

AA: So the photograph effectively recharges the old centre of the city with its own history, and in that sense functions as public art.

SD: Absolutely. But rather than fetishizing a historical moment, this photograph condenses it. I tried to condense as much as I possibly could into one image. Note that the title is very bland, with just the date and location. People have been clamouring to have some kind of plaque with a phrase or a paragraph that explains the events we've depicted. But I wanted to avoid that. I'd rather that the photograph produce a conversation between people. And, in fact, it has. I've seen the image prompt many people at the site to ask others what they are looking at. They want to know when and why the historical events depicted took place. People want to talk about the events. And that interests me very much.

A lot of conventional public art uses a plaque to explain why something that would normally be found in a museum has been placed out of doors, or what some man on a horse accomplished in this or that particular location. Such works become subordinate to their explanation. In contrast, I wasn't interested in the image conveying a single message. I was more interested in facilitating a conversation between people about a historical event, a series of historical events. In that sense, even the book in which this interview will be published is very much part of that conversation. And I'd rather something as multivalent as a book pry open the photograph, or elaborate the discussion about the photograph, than a single plaque that reads: "On this spot, on August 7, 1971, Police Beat Up Some Hippies."

[Tags: Photo Essays, Rights & Justice.] ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: