[Editor’s note: Under the White Gaze originally ran as an exclusive Tyee email newsletter last fall. We’re republishing the full series of those essays on our site this month. This essay, the eighth in the series, was originally titled 'Attack of the Shutdown Commands.']

Look, I didn’t set out to write about whiteness.

It was always an uncomfortable topic for me growing up. Whenever I happened to use the word “white,” my family would stop me for being what they thought was politically incorrect. “You mean Caucasian,” they’d say, not knowing the term was actually part of the racist taxonomy used to justify slavery.

My big interest starting out as a journalist was to reflect the ethnocultural diversity of my home, Vancouver.

But one can only pursue representation for so long before wondering why people of colour are misrepresented by media in the first place.

The more I wrote about ethnocultural diversity, the more I noticed whiteness as the other side of the coin — defining itself as “mainstream,” defining what counts as Canadian and defining how racialized people are portrayed.

I’ve caught myself writing stories under this white gaze, which is why I decided to create this project to investigate why and how it’s become so normalized in journalism.

Guess how some of our readers responded?

They told me whiteness shouldn’t be talked about.

A couple of readers accused me of being “driven by hate” and that I should “go to prison” for it. Of course, I got the classic “good for you to go back to where your ancestors came from and live in the culture you love more.” Another said the divisiveness I encouraged through my “unscientific, in-your-face sociology” could result in more white nationalism. And apparently, “The beneficiaries of increasing race consciousness among whites will, of course, be the Conservatives.”

Some were less angry but still upset, accusing me of “reverse racism.”

Only a minority of readers reacted this way. But their comments deserve highlighting because they represent a pattern of how people talk about — and try to avoid talking about — race.

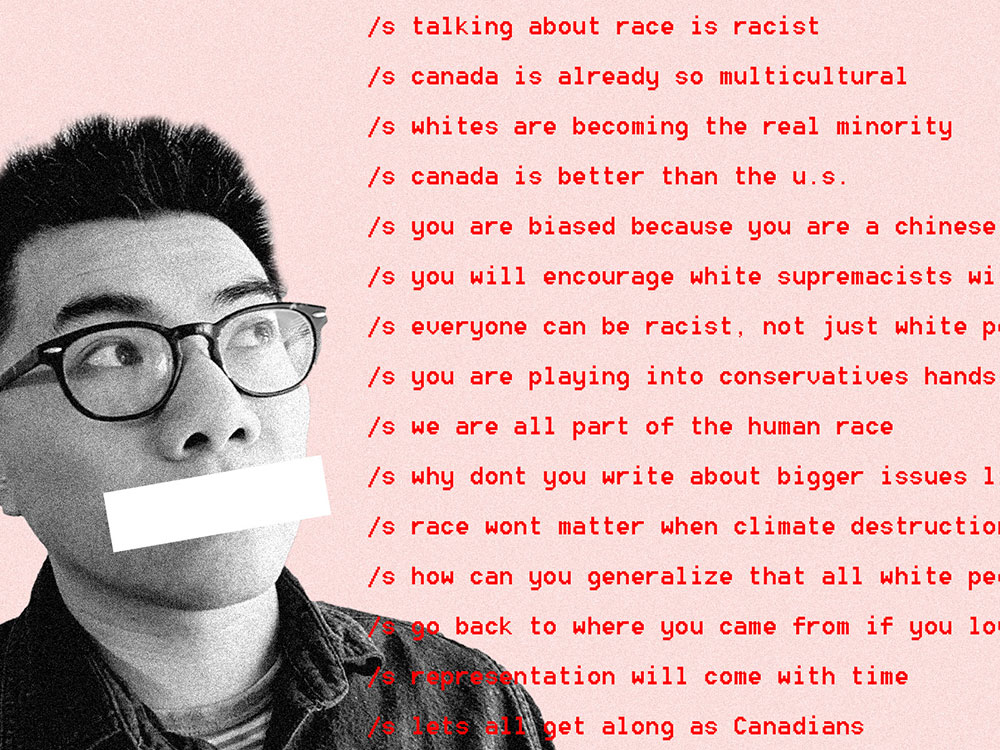

The comments read like shutdown commands for a computer, the control-alt-delete of conversations on race, and whiteness and privilege in particular.

Let’s have a closer look at some of these shutdown commands, and why they deserve to be challenged.

It’s racist to talk about race!

One of the first emails I received when we announced this newsletter read: “interesting how you chris will start to promote more Racism in our country rather then be part of a solution [sic].”

I also got a bunch pointing out that we’re all part of the human race, so I should “get past this identity politics bullshit and accept that we are all essentially the same.”

These readers seem to define talking about racism as a highlighting of difference, which divides people and is bad. This assumes that if we don’t talk about race, we can all live together in unity.

But we know that racial inequality exists, and that it intersects with all kinds of inequality: gender, labour, wealth, housing, education, etc.

Accepting that “we are all essentially the same” erases and denies racism and all racial experiences.

In the words of the American scholar of multiculturalism Robin DiAngelo, “Unequal power relations cannot be challenged if they are not acknowledged.”

You should focus on the 'bigger issues,' not race!

I get this reply a lot.

Climate change is the biggest of the “bigger issues” cited. As one reader said, “it will matter little if the victims are white or Asian, LGBTQ or otherwise, whether we experienced intergenerational trauma, or were raised in loving, tolerant, liberal, racialized families. The ultimate outcome will be extinction for all of us, without distinction.”

But this argument ignores that crises have systemic and social dimensions, with the vulnerable and marginalized hardest hit. The UN itself has noted this, through lenses such as race and gender.

Take the pandemic in B.C. Sure, all humans have a body that can catch COVID-19. But as other journalists and I have reported, the neighbourhoods with the most cases are home to people of colour who work frontline, blue-collar jobs.

Our immigration policies brought many of these people over to fill our labour gaps. And some employers’ labour conditions, such as a lack of sick days, put many at risk.

B.C. had its first taste of a heat dome last summer, linked by scientists to climate change. Sure, all humans have bodies that can have a heat stroke.

But Canadian studies have noted that Indigenous peoples, racialized folks and those with low-incomes are the most susceptible to extreme weather events like these — the result of systemic inequality when it comes to access to health care, overrepresentation in outdoor jobs and exposure to air pollution.

A meteorologist quoted in the Washington Post put it succinctly: race is “inexorably” linked to climate change because it dictates who benefits from the activities that produce planet-warming gases and who suffers most from the consequences.

Whatever the crisis, let’s not pretend we’ll all be hit equally.

You can’t have a white gaze in a place that’s multicultural!

White readers have told me that white privilege, along with the white gaze, don’t exist in Canada anymore due to the “demographic decline” of white people. They frequently cite census data on the ways white people are now — or about to become — the “new minority.”

“White ain’t what it used to be and stoking this ’white privilege, white gaze’ is boring and utter nonsense,” wrote Allan. “My lawyer is Asian, my dentist is Asian, my banker is Asian, a Vietnamese owns the barber shop where I get my hair cut. I buy my fruit and vegetables at a Chinese-owned market.... You obviously don’t like stats.”

Some readers have said that racial equality must exist because they see more and more people of colour around. Allan has a seemingly higher bar, describing racial equality as the ability to hold jobs and own property.

Sure, these are important rights, especially considering Canada’s racist past.

But a white man having an Asian dentist doesn’t mean that structural injustice is gone. Instead, let’s consider American political philosopher Iris Marion Young’s “five faces of oppression.”

Oppression, according to Young, is when a group experiences exploitation, marginalization, powerlessness, cultural domination and violence. Even in a liberal democracy, you can find oppression by this definition.

No matter how multicultural the Canadian population, presence doesn’t necessarily indicate power. Imagine a city where people of colour are the majority. Compared to their white neighbours, do they have equal institutional, social, symbolic, cultural and economic power? Do they have the same freedoms of self-determination? Are their differences affirmed or admonished?

Remember the story I shared with you about Richmond, B.C.? The city’s population is mostly of Chinese descent. But the moment a Chinese sign or ad goes up, out come the cries of it being un-Canadian and exclusive.

Of Young’s five faces of oppression, marginalization and cultural domination are all too common in Canadian journalism. The white gaze in media persists because it is the perspective by which diversity is considered.

You are biased because you are a racialized journalist writing about race!

This is a common attack on racialized journalists. During the run of this series, I’ve been accused twice of biased journalism due to being in the pocket of China’s communists. (Hmm, I wonder why!)

Look, journalists are professionals. We are governed by industry standards and ethics. It’s degrading to accuse a journalist of colour of throwing professionalism out the window because they can’t help but lose all cool when reporting on a story they have some familiarity with.

It’s not unusual for journalists to report on — or develop a beat on — areas that we have expertise and experience with. An Abbotsford journalist familiar with hydrology and the geography of the Fraser Valley would be invaluable at a time of flooding.

Any journalist reporting on a diaspora they grew up in would have an insider’s perspective on which questions to ask and which inequalities to interrogate.

Journalist Angela Sterritt at the CBC, who is from the Gitanmaax Band of the Gitxsan Nation, told The Tyee that she’s been accused of being an “advocate” for Indigenous peoples and causes.

But as she continued to fight for important stories involving Indigenous peoples to be told and told accurately, her positionality and understanding was eventually considered an asset.

Expertise and experience are strengths. And if there is a story that journalists feel they cannot cover fairly, we do indeed step away.

Just don’t see colour!

Do you remember what John Horgan said in 2020?

During a debate, the B.C. premier recalled his youth playing sports with Indigenous and South Asian kids, saying, “I don’t see colour.”

People were quick to challenge Horgan. “If you don’t see colour, you don’t see us,” tweeted Sunny Dhillon, the former Globe and Mail journalist who’s been outspoken about being the lonely person of colour in majority white newsrooms.

(Horgan would later apologize).

Tyee writer Crawford Kilian wrote about Horgan’s comment as a learning moment: “That’s what I used to tell myself, too. Then I came to learn what Horgan is being made aware of now. That to claim to not see colour is to imply you are blind to systemic racism and therefore can’t be counted on to work to remove its structural barriers.”

It’s a very Canadian example of how we’re not used to talking about race, and that many people still think it’s possible to arrive at a post-racial world where race doesn’t matter.

Another reason is that we tend to take these discussions personally. Some readers, who are white, thought I was saying they were bad people, and took the time to tell me that they were “raised to accept all.”

The point of doing journalism that touches on race isn’t to separate good people from bad racist ones. The point is to examine how our society is made up of racial inequality and racial experiences, and explore where we all fit in.

It can be difficult to see. It’s uncomfortable, and it’s disarming. As Peggy McIntosh, the American scholar known for her research on white privilege, said: “I was taught to see racism only in individual acts of meanness, not in invisible systems conferring dominance on my group.”

Journalists who write about race are holding society accountable, just like with any other issues.

Anyone using a shutdown command to silence this kind of reporting... well, they’re upholding the current status quo of racial inequality and invisibility.

Discussion questions

- How do you initiate conversations with others on racial inequality?

- Have you noticed other “shutdown commands” than the ones we discussed in this essay? How have you responded to shutdown commands?

- Do you think there’s anything about Canada that makes it especially difficult to talk about race?

Readers’ corner

Leslie Hill: “When people refuse to examine their own inner responses/conflicts over issues of race there can be no real change. Your series has been brilliant, I think, in waking people, including me, up to the kinds of media coverage that keep us blind to racism.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: