This story was produced in collaboration with Hakai Magazine.

One place to start is Google Earth. Type in “Fairy Creek.” Watch the planet swivel round to Canada’s west coast and zoom into Vancouver Island, green from a distance but gathering grey-brown splotches as the clearcuts come into range.

There’s Port Renfrew, the logging and fishing town at the south end of the West Coast Trail; beside it, tucked into the estuary where the San Juan and Gordon Rivers spill into a broad bay lined with mammoth driftwood, is the Pacheedaht Nation’s reserve, just a few dozen bungalows and trailer homes. Six kilometres east of here — shockingly close — the watershed begins: A dark green U-shaped valley, walled off on three sides by steep ridges whose conifer-quilted slopes drain through a multitude of creeks into a single artery that wiggles westward down the valley bottom, headed for the sea. That’s it. The last intact valley of ancient coastal temperate rainforest outside of a park on southern Vancouver Island, one of the very few like it left on Earth, and by far the closest to a pub.

This proximity to civilization has until now been a threat. How Fairy Creek evaded a century of industrial logging that liquidated over 97 per cent of B.C.’s big-tree old growth is a mystery. It’s a three-hour drive from the capital of a province built on old-growth logging. There’s a sawmill 15 minutes away. The surrounding valleys were long ago obliterated. But now that Teal-Jones has been licensed by B.C. to log one-sixth of the valley, the same roads that could destroy Fairy Creek have become its greatest salvation. The ease of access has allowed mothers and students and hippies and elders and politicians and activists and — most crucially — Indigenous peoples from all across this coast to flood into the region, maintain a thriving base camp, and run the rotating blockades that have kept the saws at bay for the last 10 months.

The theatre of operations includes Caycuse Watershed, a bigger, more sprawling complex of valleys and ridges and rivers and creeks just north of Fairy Creek that industry’s been picking away at for years, but which still has some huge pockets of unfathomable trees. This was where I started.

I caught the first ferry from Vancouver to Nanaimo on May 25, eight days after police began enforcing a court injunction authorizing them to clear the blockades so that the logging could resume. In those eight days, the RCMP apprehended over 60 people. They got 55 more that morning while my ferry crossed the Georgia Strait.

“You’re not planning to join them, are you?” asked the officer checking my credentials at kilometre 37 of South Shore Main. The RCMP have their own blockades, playing leapfrog with those of the forest defenders — each new blockade a little further from the cut block than the last. “A lot of journalists are embedding themselves among the protesters once they get through.” He peered through the windows of my rental car, frowned at the tent and sleeping bag, but eventually let me through on the strength of an email exchange with my editor I’d saved on my phone (there is no cell service inside this theatre). No doubt my white skin helped. A police car escorted me and a CTV cameraman six kilometres up the road, where we reached a somber scene.

Some 30 protesters were corralled on the side of the road, waiting to be taken to the nearest station. The RCMP were trucking them out three at a time, a process that took 11 hours. The arrestees were given the option of signing a statement promising not to return in exchange for being set free on the spot — doing so, however, would have elevated the consequences of any future arrests. Nobody signed the statement.

A few kilometres further up this road, where the RCMP wouldn’t allow me to go, loggers were falling giants. Eight of those giants were occupied by tree sitters, camped hundreds of feet up in the canopy. By the time you read this, those sitters have been plucked out by helicopter and the trees they were tied to are dead. None of that was visible, or knowable, from that drab patch of logging road where nothing much was happening. That was of course the point.

There was a bit of drama on this spot four hours earlier, when over a dozen RCMP trucks blazed in and skidded to a halt and declared the five dozen blockaders to be under arrest. Perhaps coincidentally, this particular blockade had a high proportion of Indigenous members that day, most of whom scrambled into their cars in terror when the police roared up. “That was good for me to see,” a white woman in her 50s among the arrestees told me. A fifth-generation islander from a long line of loggers, she was here to make amends; like many other settlers, she was getting a crash course in truth and reconciliation behind the scenes. “It made me wonder what they’ve been through at the hands of the police when no one was around to see.”

A strip of yellow crime-scene tape separated the journalist corral from the arrestee corral, while 15 officers looked on from the middle of the road. Everyone was bored and suspicious and annoyed. Everyone was wasting everyone’s time. The situation felt contrived by someone or something far away and high above. It felt designed to illuminate futility — for the police, of quelling the protests; for the protesters, of stopping the logging; for me, of trying to capture what was going on in the space of a recorded conversation. This was all set into motion long ago, and everyone, including me, stuck to their script.

I asked if anyone on the other side of the yellow tape would like to chat and was met by dubious looks. White journalists have been oversimplifying and misrepresenting this scene for weeks now, in particular the Indigenous aspect of the story. It’s a subtle thing, but glaringly obvious to those on the receiving end, the way so many of us have reported on the conflict between the Pacheedaht Nation’s elected and hereditary leaderships with a tone of smug colonial derision. Look how divided they are.

A red-headed young man agrees to speak with me, but he’s interrupted by a woman with a Land-Back mask and an air of authority. She is Kati George-Jim, the niece of the Pacheedaht Elder Bill Jones.

Bill Jones has been passionately and eloquently speaking out in defence of the movement, in defence of the ancient rainforest, and also in defence of his nation’s right to be divided on an issue that has divided every community on this island, all the way up to the premier’s own party. Jones began speaking out a month ago, right after elected chief councillor Jeff Jones issued a statement asking the blockaders to go home. At that point the blockaders, who called themselves the Rainforest Flying Squad, were still almost entirely non-Indigenous and had already come under fire for not having taken the time to build a relationship with the Pacheedaht. The nation operates three sawmills in this region, including one specifically designed to handle large old-growth cedar; they receive a cut of stumpage fees from the province, an agreement that includes a promise not to criticize provincial forestry policy. You could call that consent, or you could call it a hostage situation.

“We’re playing this guessing game between all these protesters and where Pacheedaht stands, and we stand in the middle,” the Pacheedaht’s former chief councillor, Arliss Jones, told The Tyee in a rare interview (the Pacheedaht have been understandably reluctant to speak with the press). “So maybe things didn’t happen perfectly. Nothing ever happens perfectly. But I’m grateful that the protesters are there to protect the territory against these huge logging companies.” That was in March, shortly before her successor, Jeff Jones, asked the protesters to leave. Then Elder Bill Jones came out asking them to stay.

This much is clear: There are fewer than 300 surviving members of the Pacheedaht Nation, and the press never noticed them until now.

Bill Jones’s intervention resuscitated the Flying Squad’s moral authority at a crucial moment, just before police began arresting blockaders. Five days before I arrived, Jones’s niece George-Jim was aggressively arrested along with another protester three kilometres up the road from here. The entire incident was captured on film: She and the other man trail a police officer as he walks through their debris-strewn blockade; as the officer nears a school bus blocking the bridge’s far end, he turns and suddenly grabs the male protester, who resists being thrown to the ground; George-Jim orders the officer to let the man go, shouts that nobody’s obstructing anything; the policeman responds by grabbing her as well. He’s a very large man, now wrestling with two people, both of whom are shouting that they’re legal observers, that this is not a legal action. The officer twists George-Jim’s arm behind her, doubling her over, then grabs her neck and keeps her bent while pinning the other man against the side of the bus. The officer knows he’s being filmed, keeps glancing at the camera with wide bewildered eyes. He has the look of a man who has set into motion a series of events he can neither control nor escape. The scene ends when three more policemen rush forward to back up their comrade and a hand is thrust in front of the camera.

Five days later, George-Jim was back under arrest and talking to me, looking over her shoulder because a police truck had just arrived to take three more people to the station.

Everything was happening too fast. We, too, were locked in a dance we couldn’t control or escape. But the wheels were in motion. Quickly, before they hauled her off, we talked.

“There isn’t an opportunity to have reconciliation, or land back, or anything,” she said, “unless there is time taken to have a relationship with the land, to assess what the damage has already been. To be able to have relationships with our own family again. Like my uncle Bill says, it is our reawakening, it is our spiritual duty and our love for the land that will bring us to a place where we no longer have that division through colonialism, or division through systems or people or places that are going to divide us.”

I didn’t want to bring it up, but suddenly I heard myself asking what she considered the best possible outcome to this conflict given that the Pacheedaht were themselves divided over the issue of old-growth logging. She was taken aback.

“I think it’s a very misinformed narrative to say that communities are divided,” she said. It was and remains the Indian Act that created this divide, stripping First Nations of their land, their governance structures, their very children, while forcing a pseudo-democracy down their throats. “Does everyone agree with their family? Does everyone have the same perspective or experience? No. So, like my uncle Bill says, within Pacheedaht, with every other type of band nation or community, it’s a civil war. It’s a civil war funded by Canada, and it’s a civil war that British Columbia is founded on. Because British Columbia couldn’t exist without all this stolen land.”

This is true, of course, as the courts have affirmed in every case that a B.C. First Nation has found the resources to pursue — over 90 per cent of this province was taken without even the veneer of legality conferred by treaties elsewhere in Canada. “So if you’re talking about division in the community, what the division is is colonialism, and intergenerational trauma, the violence, the enforcement, the oppression, everything that segregates you either to a reserve land, or off-reserve land — it’s all back to dispossession of land, dispossession of your spiritual and ancestral right to be in relation to the land.”

The words poured out of her. I wanted to go for a five-hour walk through these woods with her, climb a tree, say that I agree with everything she says and add but I’m a white settler — who am I to tell the elected chief and council of the Pacheedaht Nation that I reject their authority? Instead, I ask if she is optimistic that the current protests can alter the trajectory of events.

“You know what I’m optimistic about, and have no doubt in my mind? Indigenous law. So that is not a protest, I am not a protester — ” but now three arrestees are marched into the back of a police truck and George-Jim steps back amongst her crew to cheer and sing to them. It takes a long while before the truck actually drives off. When the dust settles, those left behind huddle with their backs to journalists and cops alike, to privately discuss next moves and future strategies. This interview is over.

I drove back to Lake Cowichan, the postcard of a town 40 kilometres east of Caycuse that houses the closest police station. On a bridge over the Cowichan River, two high school girls are holding signs that read “FORESTRY FEEDS MY FAMILY.” Every second vehicle that passes by honks in support.

I asked if we could talk. They grinned and nodded, delighted.

“It’s not true that there’s only two per cent left,” insisted the one who did all the talking. “There are 12,000 football fields of old growth there,” she said, gesturing west toward Caycuse and Fairy Creek. “They’re not going to log all of it. And for every tree that’s cut they plant three or four more.”

Five hundred metres away, arrestees were emerging from the police station, blinking in the sun, wondering how to get their cars back. The girls on this bridge inhabited a separate universe. I stifled the urge to pull out my phone and show them satellite images of Vancouver Island. They were 14-years-old. They loved their dads. What they knew was that 12,000 football fields of old growth is a lot, and “everyone has the right to protest but this has gotten out of hand.” Five days from now, the grown-up residents of Cowichan will turn out for a pro-logging rally, carrying the exact same signs: Forestry Feeds My Family.

“I’m sorry you can’t go to work. You got a right to work, and you got a right to be angry. I hate that all these hippies from the city have showed up, too. But man, there’s fuckin’ nothing left out there. We’re fighting over guts and feathers. There’s a shred left, and once that’s gone then where are you gonna go?”

It was the next day and I was on a logging road that leads to the edge of Fairy Creek, waiting for the police to show up, listening to the only land defender I’ll meet who knows how to talk to a logger. Duncan Morrison looks like one, talks like one, grew up among them in Sooke, a logging town 80 kilometres south of here. But he makes his living taking tourists out to see big trees, and when he saw the road above us getting punched all the way up to the edge of the headwaters last summer, he and some friends pitched their tents and helped start the current movement. That was in August 2020.

Over the course of my three days in Fairy Creek and Caycuse, I saw various groups of loggers gather below the blockades like salmon at the mouth of a spawning creek that’s been choked off by debris. Whenever I tried talking to them, they got in their trucks and rolled up the windows. At best. But here’s Morrison standing beside an F350 with the windows still rolled down, talking and swearing away. At first, I thought he was a logger himself. “I love yellow cedar,” he was saying. “It’s amazing fucking wood. But we’re not gonna be falling 2,000-year-old yellow cedars forever.”

He thanked the man in the truck for hearing him out. The window went up and the truck rolled off, and I introduced myself to Morrison. He agreed to chat and took a seat on the back of a tow truck whose driver was also waiting for the police to show up (that driver told me he supported the land defenders, too).

“This is a crisis 150 years in the making,” Morrison said. “We either act now and transition to second-growth forestry or we go off the cliff. And then who’s going to suffer the most? The workers, if those mills aren’t retooled to mill second-growth.”

I asked him if he’d meant what he said to the logger about hippies invading these woods, and he laughed.

“I’m a big hippy too,” he assured me. “It’s an interesting juxtaposition to be in, between these rural resource communities and all these people coming from these urban areas. I’m glad that the people are coming and showing up, but I think there’s a lot of things people don’t understand, coming from the city. These resource communities are simply a symptom of the demands that urban areas have for resources and people become disconnected from the stuff they buy and where that comes from. These working men are just working to provide a need. There’s a demand, you’ve got to follow that. Who’s buying this old-growth timber, who’s using it? Those are the people we need to have the conversation with, not the working-class man who’s just trying to feed his family.”

Yet here you are, I said. Blocking the working-class man who’s trying to feed his family.

“Well,” he said, “these blockades are simply a result of failure of government policy, and citizens are frustrated, and action is the antidote to despair.”

I asked where his community, Sooke, stood on the issue. “Divided,” he said. “Everyone’s divided. I’m divided myself. I understand that this whole province was built on the back of forestry, and we wouldn’t even be able to go to these places if there weren’t these resource roads to take us. Forestry is always going to have an important part in our economy, but I understand that things need to change. There needs to be this paradigm shift while it’s still within our control. People need to understand that this shift is inevitable, and it will either be because we woke up and we defended the last 2.7 per cent, or because we logged it into oblivion, and we were forced to go to second growth anyways.”

How, I wondered, do loggers reply to that sentiment?

“They just kind of shrug,” he said. “The mentality is that there’s lots of old growth and we can keep doing this forever.”

The science, for the record, is very clear on this point. One can quibble about exactly how much old growth is protected in this province, or how quickly we’re logging the unprotected stands, or even what qualifies as old growth — 250 years on the coast, 140 years in the Interior, is the standard definition, but it’s muddied by the fact that a section of forest might be too nutrient-poor to support big trees, yet still be classified as old growth because it’s never been logged. That’s why there’s such a big gap between what B.C.’s Minister of Forests says is left and what Sierra Club says.

But nobody without a financial or political stake in the status quo believes there’s anything sustainable about logging the kinds of trees Fairy Creek and Caycuse are full of, trees that range from 250-to 2,000-years-old. There’s no ambiguity here. The Old Growth Strategic Review that Premier John Horgan commissioned in 2019, and whose recommendation to stop logging precisely these kinds of valleys he endorsed in 2020, explicitly stated that old-growth forests are not renewable. That was a central tenet of the “paradigm shift” they urged the province to embrace, which Morrison and so many others have been quoting ever since.

According to Karen Price, a forest ecologist and co-author of numerous peer-reviewed papers mapping out the province’s old growth, B.C. is on track to liquidate the last of its unprotected old growth within the next 10 years. That’s how far away the cliff is.

“I meant it when I said those loggers have a right to be angry,” Morrison said before we parted ways. “But so do I.”

He drove off, taking the left fork up to Waterfall Camp. I stayed put. The police arrived around noon, later than usual, charging up like cavalry and calming down when they saw it was just a few journalists hanging around. It’s the kinetic situations that set them on edge — masses of people swirling on the road, the journalists and defenders and media liaisons and legal observers all mixed in together; as George-Jim told me, they’re scared, too. When everything is calm and predictable, the police become easier to work with, and even seem bemused. The hippies here are strange and colourful and highly inventive.

A small group of those hippies were a few hundred metres up the right fork, waiting for the police with their hands in dragons. The police knew this, had checked it out by helicopter earlier that morning. Now the daily ritual could begin.

A dozen policemen walked up the road, sealed off the arrest area with yellow ribbon, told us journalists where we could and couldn’t go (the subject of much valid consternation and legal wrangling throughout this escapade), then read the injunction out loud to the defenders and gave them a chance to unchain themselves and walk away. They all declined the offer. I spent the next hour watching a special-forces officer operate a jackhammer to excavate the PVC pipe buried two feet under the gravel and encased in cement. This was the dragon. Each defender had their hand chained inside one. Another six defenders were standing with the journalists behind the yellow ribbon — they had donned the fluorescent vests that turned them into legal observers (ever since the video of George-Jim’s violent arrest went viral six days earlier, the police had been treating these observers with respect). The observers sang to their bedragoned comrades, soothing them as best they could — having a jackhammer pound away two inches from your fingers by someone who’s annoyed with you is a nerve-racking experience.

Observing it from a safe distance, however, gets old pretty fast. After an hour I looked up the road. It led some four kilometres up, stopping 500 metres shy of the ridge. On the other side of that ridge was Fairy Creek. The place that bound all of us — loggers and police, defenders and journalists, hippies and rednecks and city-slickers — together in an awkward embrace of conflicting obligations.

I left the last dragon behind and started walking.

How can I make you feel an old-growth forest if you’ve never been in one?

We both know I can’t. Not through a computer screen. Books like The Overstory or Finding the Mother Tree will get you closer. But even they fall short. There’s no way to transmit the sensation through words alone, and all the analogies we employ to bridge the gap between language and experience suffer the same deficit. A church, a temple, a cathedral. To say that it feels sacred has the perverse effect of sounding trite, which is to say, profane.

And yet: The memory that sprang into my mind when I entered the headwaters of Fairy Creek was of the great hall in the Mosque of Córdoba, Spain, where over 850 pillars form an ancient forest of onyx and jasper and marble and granite. The forest at the top of Fairy Creek was similar. Because of the altitude, verging on subalpine, there were none of those knotted and gnarled five-metre-wide cedars you find lower down the valley; here it was all smooth vertical trunks of hemlock, spruce and Douglas fir, spaced with an eery geometry that maximized their mutual access to light and soil and water. Many of these trees would be around the same age as that mosque, which was built in 785 AD. Clouds had settled in by the time I arrived, and they smothered the treetops like a dripping ceiling. The only sound was that of several million raindrops landing on needles. Not even a bird sang.

I don’t mean to sound romantic. It’s also true that these forests are miserable to walk through, so dense it feels like hands are grabbing at your thighs and ankles with every step — and that’s the path of least resistance. It’s not a place for frolicking. You get soaked and scratched and exhausted just to progress at the pace of a sloth, without any of the grace. But every so often you can get a moment like the one I had when I sat down and stopped trying to do anything or go anywhere or think of ways to change my premier’s mind. A moment where it’s just you and an infinity of ancient columns that disappear into a belly of cloud like so many umbilical cords, and then you think: if only everyone on Earth could have this experience.

Not because of these forests’ contribution to carbon storage and biodiversity, though of course there is that, too. But really, just for the rapturous delight of brushing up against something older and bigger than we’ll ever be. Something that connects us not only to the past, but to the future. Among these ancient beings there are seedlings, too.

The next day was atrocious.

Pelting rain and howling wind, it felt like January. I wound up at Waterfall camp, the best-defended blockade of them all: hundreds of boulders and several abandoned vehicles blocked the approach to a compound built around a narrow bridge that spans a tumbling waterfall. There was a gate before the bridge, with three defenders chained together right in front of it — they’re just the welcoming committee. Inside and almost underneath the gate, a man lay on the ground, one arm buried in a dragon, tarps piled over him like blankets. He was getting pounded by rain and flecks of wood that came flying off the chopping block two metres from his head, as the support crew worked to keep a bonfire burning hot. The road was turning into a creek, sending sheets of water directly into the prone defender until one of the support crew — the chief of staff for a sympathetic member of Parliament — dug a trench around his body to divert the flow. Further along, on the far side of the bonfire, another man lay half under a school bus, also chained to a dragon. Next, on the bridge, a woman dangled in a harness three metres up in the crook of a huge log tripod. Beside her tripod, a minivan was parked in such a way that one tire wedged down the end of a sailboat’s aluminum mast; the mast stretched perpendicular across the bridge and jutted off the side of the mountain, out into space, high above the jagged rocks of the raging waterfall. A man sat at the end of the mast. If he slipped, or if the van holding the mast in place was pushed half a foot forward or backward, he would have crashed to his death.

The wind and rain were picking up and the waterfall was pounding harder every 30 minutes. A police helicopter swept overhead and hovered there awhile, just as the CBC reporter up here with me tried to interview the man at the end of the mast. “Aren’t you afraid?” the reporter shouted. No microphone on Earth could have captured this conversation. The man on the mast shouted back, “I’ll tell you what I’m afraid of. I’m afraid the ancient trees on the other side of this mountain will be cut down.”

Everyone knew the police were coming — they’d escorted me to the base of this camp — and that’s why they were all in position. But it took the police hours to arrive. They had to clear every obstacle along the way, removing the boulders on the road by hand, using a tow truck to haul the vehicles out of the way. Meanwhile we sat, or lay, or paced around, trying not to shiver. Ten supporters kept busy providing tea and smokes and hot packs, slipping into the bush to monitor the RCMP’s progress. They kept the fire stoked, then tied an enormous tarp to the trees so that it sheltered the fire, and soon everyone who wasn’t chained to something or suspended over certain death was crowded round the flames. A Cree woman from Saskatchewan, Raven, placed buckets under the tarp’s edge and tried to catch the water flowing off, but it sloshed free in a different place each time, forcing her to move the bucket over and over again.

This was the story of the blockades. A vicious updraft would fill the tarp like a sail one moment, sending spray in all directions, then implode with sudden calm the next, allowing pools of water to gather in various depressions until the next gust unleashed a new and unforeseen river to one side. The smoke from the fire was equally erratic. The police helicopter disappeared, was replaced by a drone. The road I’d been on yesterday, on the other side of the steep ridge rising a kilometre to our east, had been secured by the RCMP, and industry was now on it, logging their way up to the edge of Fairy Creek. They beat that blockade, and now this one had a day or two left barring some kind of miracle, and then what would happen?

My fingers were too numb to close the buttons of my jacket pocket. I looked out at the man on the mast and wondered how he kept so still and calm.

When the police finally reached the gate, the day was almost over. They arrested the three defenders chained to one another outside the gate and gave the support crew the chance to leave or be arrested; most left, clutching tents and belongings, making their way to the cars they’d parked far below. Then the police left, too, leaving the last few defenders there to spend the night in peace.

The following day, 29 RCMP officers returned to clear Waterfall camp. It took six special-ops officers and two helicopters to remove the man from the mast. But the day after that, hundreds of fresh defenders arrived and overwhelmed the RCMP’s checkpoint, storming all the way to the waterfall on foot and re-establishing the blockade.

The dance continued.

This clock was wound up 150 years ago. The colonial experiment was the thing that set the stage, wrote the script, built the machine and locked us all into pre-ordained, perpetual motion. You can’t see this machine on Google Earth, but if you come to Fairy Creek you can’t not see the way its parts all whir and click and spin in perfect synchrony.

They wanted the land. In order to take it, they had to remove the people who lived on it. The same forces of destruction were unleashed on First Nations and forests alike — but both are resilient, and refuse to go so easily.

The job is not yet done. All these generations later, settlers are still carrying out a mission so ingrained we don’t even perceive it. Us? Settlers? It doesn’t seem strange that the provincial capital’s daily paper is called the Times Colonist. Until it does, the colonial machine will grind on, ploughing everyone and everything beneath it, ticking along at two parallel time scales: a glacial pace in matters of justice and reform, fast as a buzzsaw in all matters of plunder. Extract, remove, oppress, enrich; that’s what this machine was built to do. Even those of us on the supposedly winning end are forced into unwitting roles — the police and the loggers, the journalists and the politicians, even the protesters, we’re all just doing our jobs. Of course, that’s an illusion — we can choose which questions to ask, which stories to tell, which trees to cut, which protesters to arrest, which laws to write. Many do. All it takes is courage and imagination.

I caught the last ferry back to Vancouver on Thursday night, after three days without internet or cell service, just in time to hear the breaking news. The bodies of 215 children had been found beneath a residential school in Kamloops. Two hundred and fifteen children who died alone, whose parents never saw their bodies, never learned for sure what happened to them.

That was one of 130 residential schools that operated across the country.

There is no distance between that story, and this one.

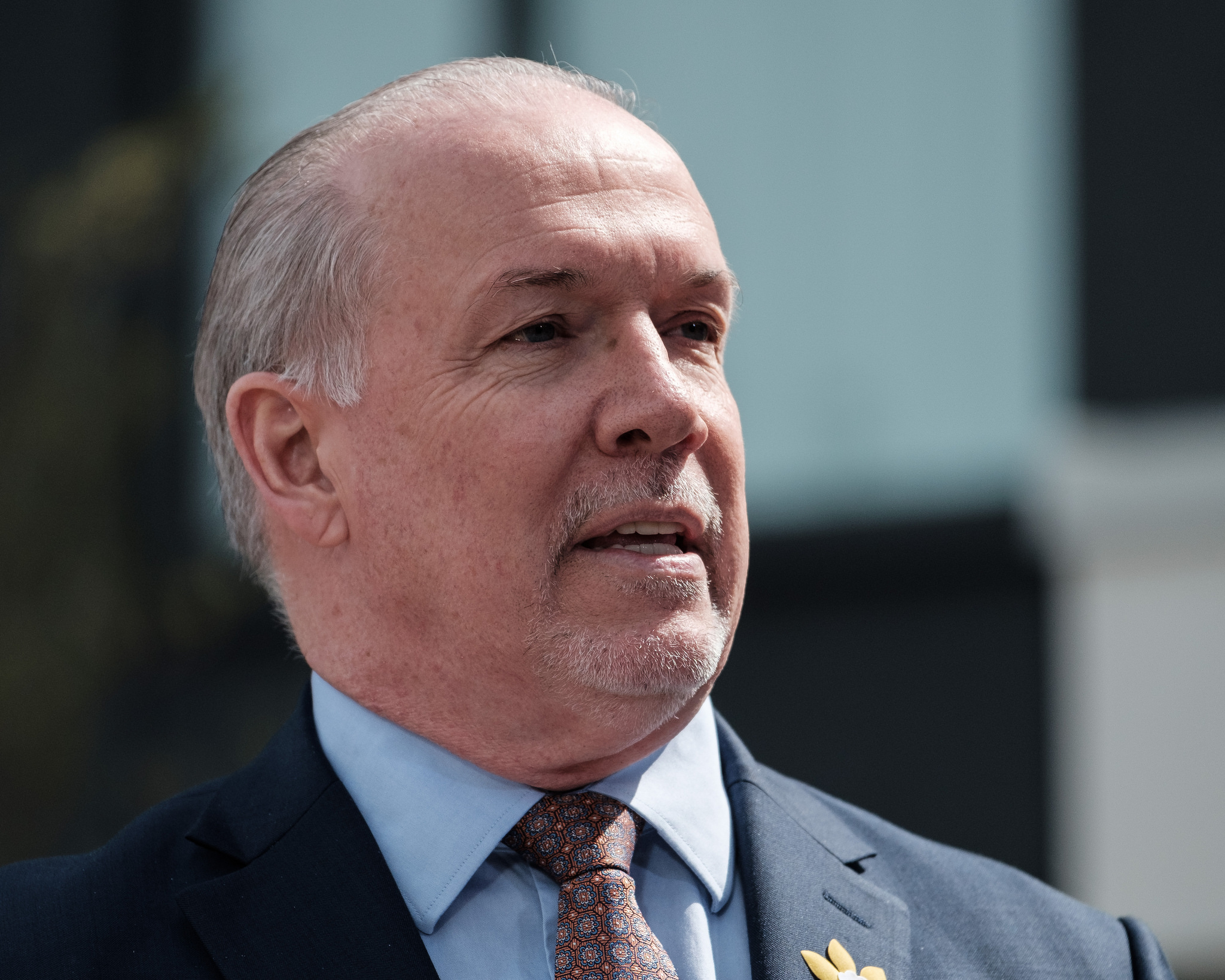

There is one person who holds the key to this machine; one person who can turn it to a different purpose. That is the B.C. Premier John Horgan whose riding happens to include Fairy Creek.

Teal-Jones claims the trees it wants to log in Fairy Creek and Caycuse are worth C$20 million. Buying them out, and compensating the Pacheedaht Nation for the revenue it will forego by leaving the old growth where it is, so that everyone can gather round the table and work this out without the sound of chainsaws in the background — this is such an obviously right first step, so easily affordable, that it should go without saying. Twenty-million dollars is the equivalent of five decent houses in Vancouver. The federal government’s latest budget earmarked $3.3 billion to preserve 25 per cent of Canada’s land base by 2025. B.C.’s share of that works out to at least $200 million. I am not the first to point this out. Nor is this the only potential source of funding.

The bigger, more crucial and complex challenge is to overcome the self-destructive logic of our colonial system. To be anti-colonial is to break a mindset that has been with us for centuries. That part is much harder. “Paradigm shift” is far easier to say than to enact, when the paradigm in question has been in place for well over a century and yielded the greatest explosion of material wealth known to human history. I know that I, for one, remain in thrall to it, betrayed by the things I say and think when I rush or act in reflex; I can and sometimes do break free, but only with great effort. And yet the costs of not making that effort are finally starting to outweigh the benefits. Arguably, they have all along.

What I think Fairy Creek can teach us is that the struggle for change doesn’t have to be futile. That imagination and courage, when tethered to empathy, can overcome seemingly intractable contradictions. The blockades were begun by settlers who faced impossible odds and failed at first to build some vital relationships. But those relationships are being built, and now Indigenous leadership is asserting itself. That leadership can and should speak for itself. Their stories aren’t mine to tell. But I can urge us all to listen.

This process might have started 150 years ago, but it won’t last another 150. Here comes the cliff. We can slow down and shift course of our own free will, or we can plummet into the abyss and see how it feels when the machine finally arrives for us. ![]()

Read more: Local Economy, BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: