On an April morning in 2014, members of the Fort Nelson First Nation tucked into a helicopter to begin a day of flying to fossil fuel company operations in their territory.

The nation’s lands are part of the expansive Treaty 8 territory that includes northeast British Columbia. A professional biologist from Fort St. John was in town and had invited employees with the nation’s lands department along for the ride.

For the rest of the day, the biologist and Fort Nelson First Nation members flew to well pads where companies drill and frack for natural gas. They looked at roads and pipeline corridors cut through the region’s black spruce forests, muskeg and wetlands. And they paused beside massive pits excavated from the earth to store toxic wastewater from the fracking process.

At each site, the biologist, who was conducting a first-of-its kind audit of fossil fuel company operations, took notes.

The audit marked a critical milestone in a little-known “recovery” plan developed a few years earlier by B.C.’s then environment ministry. The ministry was required to devise the plan because the region’s boreal caribou herds were in trouble. Fourteen years earlier, the federal government had formally listed the species as “threatened” across the country.

A cornerstone of B.C.’s plan was that natural gas companies would have to follow a suite of modest new rules known as “interim operating practices” (IOPs). An audit would determine whether or not the companies were in compliance.

Adhering to the rules would be essential if the caribou were to have even a fighting chance of survival. That’s because the plan itself accepted as given that the fossil fuel industry would proceed largely unchecked for the next half century. At that point, the region’s already threatened caribou would be so further decimated that two-thirds of their number would be gone. Presumably only then, after the companies had essentially fracked every ounce of gas out of the region’s vast gas-bearing, shale rock formations, would the real recovery work begin.

Not long after the helicopter tour, the biologist, Dan Webster, delivered the audit to B.C.’s Oil and Gas Commission (OGC). The OGC largely funded the study and is the agency that regulates fossil fuel industry activities in B.C.

For the next four years, the commission kept the audit’s findings hidden, never disclosing them to the general public or, more importantly, to the Fort Nelson First Nation whose members were most directly affected.

“FNFN never received the audit even though the [nation’s] Lands Department requested a copy of the final documents,” Chief Harrison Dickie said.

But the First Nation now has the audit, thanks to someone sending it in an unmarked brown envelope to the B.C. office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), which subsequently alerted the nation of its contents.

It’s no surprise, given the circumstances of the audit’s “release,” that the suppressed document shows that, over and over again, companies broke the very modest rules to protect the caribou. They built well pads that were far too big. They failed to place visual blocks across roadways and pipeline corridors, allowing the caribou's primary natural predator — the gray wolf — to more easily spot its prey. And they failed repeatedly to restore the sites they had developed.

Not only “was compliance low in general,” biologist and auditor Webster wrote in his report, “but… often these measures were not prescriptive enough, allowing for companies to avoid them or seek exemptions from them.”

Webster submitted his report to the OGC in spring 2014 and was blunt about the critical issue of controlling the “cumulative impacts” of industrial operations.

“The objective of managing the size of the [industry’s] footprint and impact to caribou habitat is not addressed as each application is reviewed on a standalone basis, with no long term planning required by each individual company, or between all operators within a specific core caribou area.”

A disturbing pattern of suppressing information

The leaked audit marks the third time in less than a year that the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has learned through Freedom of Information (FOI) requests and other means that the Oil and Gas Commission has withheld information from the public that casts fossil fuel companies and their regulator in a negative light.

In the first case, the CCPA submitted an FOI request to the commission asking for documents relating to unauthorized dams built by natural gas companies to store water used in fracking operations. The request included copies of inspection reports and enforcement orders that commission personnel may have issued at a number of sites where potentially dangerous dams had been built.

Only when the FOI was filed did the commission post the orders online and belatedly issue an information bulletin.

In the second case, a damaging report detailing how companies drilling and fracking for natural gas had contaminated groundwater at numerous gas well sites suddenly appeared on the OGC’s website just one day after investigative reporter Andrew Nikiforuk, who had obtained a leaked copy of the document, filed questions to the OGC about it.

The OGC had suppressed that report for four years, during which time successive provincial energy ministers claimed there was “zero” evidence of groundwater contamination due to gas drilling and fracking operations. The commission apparently never bothered to correct the ministers’ erroneous statements, and subsequently defended its decision to sit on the report because it was an “internal” document only.

And now, in a third case, we have proof that the Oil and Gas Commission held on to a damaging audit on caribou for nearly as long as it did for the damaging groundwater contamination report.

The news comes at an awkward moment for B.C. Environment Minister George Heyman. Premier John Horgan has instructed Heyman to enact an endangered species law for the province, but the premier is also clear that he supports expanded natural gas production. This means plenty more drilling and fracking ahead.

Horgan recently generated headlines across Canada when he said that his government will provide substantial financial incentives to Royal Dutch Shell, one of the world’s largest fossil fuel companies, if it proceeds with plans to build a massive liquefied natural gas (LNG) processing plant in Kitimat.

The government support of LNG strongly suggests that a tough, effective bill to protect endangered species by curbing industry excesses may not be in the cards.

If the government, however, does break from convention and ushers in a new era of protecting threatened fish, wildlife and ecosystems in B.C., it could draw important lessons from the events surrounding the suppressed caribou audit.

Lesson 1: B.C.’s glacial pace in protecting species actually places them at greater risk

The federal government first found boreal caribou to be threatened in 2000. It took the B.C. government 10 years to publish a “science update” in response. The update was required under bilateral accords with the federal government known as the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada and the Canada-British Columbia Agreement on Species at Risk Act.

The science update noted that vast swaths of boreal caribou habitat were already negatively impacted by oil and gas industry activities and warned that unless something was done to curb industry excesses there would be dire consequences for the already threatened species.

“New petroleum technologies used to extract unconventional gas from shale formations require large volumes of water, which may alter hydrology and peatland vegetation communities. The intensity of activity and infrastructure associated with unconventional gas development may have negative effects within all Boreal Ranges, especially Core habitats,” the update concluded.

The following year, the environment ministry issued its “implementation plan” for the “ongoing management” of boreal caribou. The 2011 plan, later given the dubious title of a recovery plan, laid the groundwork for the 2014 audit. It’s anyone's guess how much further the province’s threatened boreal caribou herds declined in the intervening years.

Lesson 2: If recovery means unchecked industrial development then recovery equals extinction

B.C.’s 2011 plan accepted as given that oil and gas industry activities would continue for decades. The government was simply unwilling to give up even a portion of oil and gas revenues. This blanket acceptance of essentially unchecked fossil fuel developments meant the recovery plan’s goals, such as they were, were weak and hopelessly compromised from the outset.

Goal number one was to “decrease the expected rate of decline” in caribou numbers.

Goal number two was to “significantly reduce the risk” that boreal caribou would be extirpated or face localized extinction in four of six boreal caribou populations in northeast B.C.

These goals signalled that the provincial government anticipated, and indeed accepted, that many, many more caribou would die than would be born or “recruited” in the years ahead.

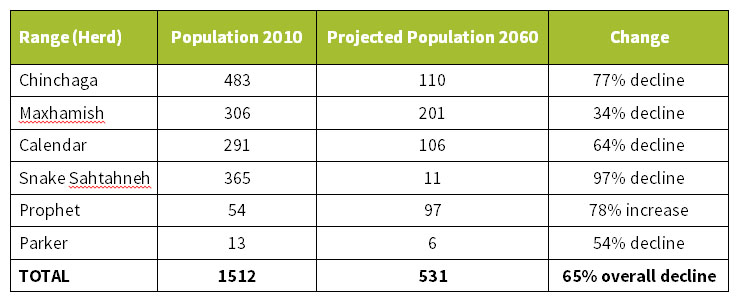

In two of the six sub-populations the anticipated losses were so high they would likely result in eradication of the caribou. In three of the remaining four populations, the numbers would fall precipitously for 50 years, at which point the real work of “recovery” would presumably begin. And in only one of the six populations would the numbers theoretically go up.

These shocking outcomes, according to the recovery plan itself, were actually developed by a team of biologists and land use analysts using computer models, but the government omitted them from the publication. Given the numbers the models spit out, it is no wonder they never made it into the report.

The numbers do exist, however, in a presentation a senior B.C. civil servant made to an interprovincial caribou conference at Alberta’s Foothills Research Institute in 2012. The numbers presented by Chris Ritchie, now head of the ministry of forests, lands and natural resource operations’ caribou program, projected a staggering 65-per-cent overall decline of boreal caribou in Fort Nelson First Nation territory by 2060. In the worst-case scenario, the “recovery” plan anticipated a 97-per-cent decline in one herd from an estimated 365 animals in 2010 to just 11 within 50 years.

In summary, B.C.’s “recovery” program envisioned losing more than 1,000 members of a threatened caribou population between 2010 and 2060. Only after those losses, and time had elapsed, would the real “recovery” work actually begin.

Just what that work would entail is anyone's guess. But if current practice is any indication, it would almost certainly include killing wolves — a controversial hallmark of modern recovery efforts just about everywhere that caribou numbers have declined.

Lesson 3: Rules are meaningless if they aren’t enforced

Audits assess whether goals are being met and rules are being followed. If the goals aren’t being met, then problems identified in audits can be rectified by changes on the ground. If audits reveal that rules are repeatedly broken, then fines and/or charges may be necessary to steer things in the desired direction.

According to Ritchie, there was a fair amount of “consternation” in the natural gas industry that special rules governing company operations in caribou habitat had to be developed at all.

Once forced to do so, however, industry representatives worked with the OGC officials and hammered out a modest set of new operating practices. The rules were to be embedded in permits issued by the commission to individual companies operating in areas where caribou were known to reside.

“They [the OGC] refer to the operating practices, figure out which ones are going to be appropriate and effective, and they are converted to permit conditions, which is where a legal requirement is applied. Then there’s an expectation that the industrial operator will meet those objectives,” Ritchie told delegates attending the Alberta caribou conference.

Contacted by phone in early April, Ritchie said it is possible that the Oil and Gas Commission might choose not to embed conditions into permits. If it did so, however, the commission would have to demonstrate that its choice did not result in a “material adverse impact” on caribou habitat.

Ritchie also said that he understood the OGC had conducted “a review” of company compliance with the permit conditions, but he had not seen a copy of that review. A draft of the original audit is dated May 29, 2014, its front cover prominently carrying the OGC’s distinctive blue and green logo on the top left corner and it includes copies of inspection forms that Webster filled out during his field visits.

In his audit of one Penn West operation, Webster gave the company a “fail” grade on six issues. Three notable problems included:

- a pipeline right-of-way nearly double the allowable width;

- a gas well pad built right to the edge of a wetland with no protective “riparian” forest left standing along the edge; and

- the ground falling or “subsiding” by one metre at one company operation. The audit does not indicate what caused the soil to subside, but water withdrawals, gas drilling and fracking can trigger such events.

An outstanding question that may have to await the outcome of a future FOI request is whether the rules developed by the OGC and its company clients were ever actually embedded in the permits themselves. If the commission did not write the rules directly into the permits it would result in a disastrous outcome, said a lawyer with expertise in endangered species and the law.

“In B.C., there’s no general provision against destroying caribou habitat. And the only way you protect that habitat is through putting specific conditions in a permit. If you don’t, then you're back to the general problem, which is there’s nothing preventing the company from destroying that habitat,” says Sean Nixon, a lawyer with Ecojustice, Canada’s largest environmental social justice law organization.

Lesson 4: An independent agency should be the enforcer, not the Oil and Gas Commission

The OGC was created in 1998 as a “one-stop shop” for regulatory approvals. A central question, however, is whether an agency with such a mandate can effectively police the industry it issues development permits to, or whether the critically important role of monitoring and enforcement should be assigned to another agency. This question has been addressed at least twice previously when other provincial agencies or ministries were examined to see whether they were effectively protecting natural resources. In both cases, the conclusion was that a separation of powers was essential to ensure proper oversight.

In 2007, a special legislative committee, consisting of both Liberal and NDP MLAs, was tasked with reviewing and making recommendations on "sustainable aquaculture" in B.C.

The committee noted in a report that while B.C. claimed “to have the most stringent regulatory regime” for fish farms, there were “key areas” where oversight of the industry could be strengthened.

One problem the committee identified was the inherent tension within the lead agency tasked to oversee the industry (the agriculture and lands ministry). The ministry essentially had powers to both police the industry and review and approve industry applications.

The committee concluded the model was problematic, noting in its May 2007 report:

“There must be a clear division between Ministry of Agriculture and Lands and the Ministry of Environment. Programs that promote aquaculture development should be within the Ministry of Agriculture and Lands. All protection, regulation and monitoring of the aquaculture industry must be within the mandate of the Ministry of Environment.”

This same idea was articulated nine years later in Auditor General Carol Bellringer’s report on the effectiveness of the ministry of energy and mine’s compliance and enforcement efforts over the mining sector.

The report followed the horrific events at the Mount Polley mine where a tailings pond dam failed, triggering one of the worst environmental disasters in B.C. history. Bellringer said that in order to have a credible shot at preventing another similar event, the government needed to remove compliance and enforcement powers from the ministry of energy and mines and turn it over to another agency.

“MEM’s role to promote mining development is diametrically opposed to compliance and enforcement. This framework, of having both activities within MEM, creates an irreconcilable conflict," Bellringer said.

It's hard to see how a similar conclusion cannot be reached when examining the Oil and Gas Commission’s compliance and enforcement efforts.

As with the aquaculture and mining examples, the OGC is effectively saddled with a contradictory mandate to both promote and regulate the gas industry. Time and again, in just one year, the commission's credibility as a tough regulator has been called into question. The promoter has failed to be the enforcer.

Taking the exit off the highway to extinction

Boreal caribou are far from the only forest-dwelling caribou at risk in B.C. All across the province woodland and mountain caribou populations are dwindling, and in many cases, rapidly. In the forests of West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations territory west of Fort St. John, dogged efforts are underway to stave off extinction of the Klinse-Za caribou herd by capturing maternal caribou and placing them in pens to raise their calves. Far to the south on lands straddling the B.C./Washington State border, the Selkirk caribou “herd” is now functionally extinct with just three animals.

For the boreal caribou in Fort Nelson First Nations territory, a reprieve of sorts has come. Gas industry activity in the area is currently at a virtual standstill because of poor economics. But the drilling and fracking will return, and if B.C.’s current “recovery” plan remains in place, the region’s caribou are doomed.

Getting off the highway to extinction in FNFN territory must involve a suite of initiatives. In the aftermath of the damaging and suppressed audit, four seem obvious:

- A tough new provincial endangered species bill must be passed and passed soon.

- Effective curbs on fossil fuel industry operations must be enacted.

- New operating rules designed to protect endangered species must be written into permits and must be enforced.

- The Oil and Gas Commission should no longer be tasked with monitoring and enforcing the industry that it also promotes.

And then there’s a fifth action, without which none of the above works. That is doing what the provincial government said it would do and implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Truly acknowledging that industrial developments will occur only after the free and informed prior consent of affected First Nations has been obtained is the only honourable way forward.

What’s happened to date is the height of dishonourable conduct.

Taking members of an affected First Nation for a helicopter ride; having them participate in an audit in their traditional territory; not responding to the nation’s requests for a copy of the audit that is kept under lock and key for four years; and then the nation learns of the audit’s contents through a third party.

The Fort Nelson First Nation is just one of a long line of First Nations that deserve far better.

This article was supported by those who generously contributed to the Rafe Mair Memorial Fund for Environmental Reporting on The Tyee. To find out more or contribute, click here.

Read more: BC Politics, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: