A race-based fishery that violates the equality rights guarantee in the constitution, or, a legitimate attempt in the absence of treaties and definitive court rulings to begin a process of reconciliation between the Crown and aboriginal peoples over the fisheries?

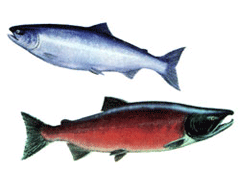

In broad terms, these were the questions facing five justices of the British Columbia Court of Appeal in R. v. Kapp, a dispute over a 24-hour sockeye salmon fishery on the Fraser River.

At 7:00 a.m. on August 19, 1998, the Department of Fisheries and Oceans opened the sockeye fishery at the mouth of the Fraser to commercial fishers from the Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Burrard First Nations for 24 hours before it opened the fishery to the rest of the commercial fleet.

This advance opening was part of a "pilot sales agreement" between the First Nations and the DFO under its Aboriginal Fisheries Strategy. The parties intended these agreements as temporary arrangements that would provide more aboriginal fishers with access to the commercial fisheries, bridging the treaty negotiations that would establish a more permanent aboriginal presence in the commercial fisheries.

'Racial classification system' charged

In response, nearly 150 commercial fishers, including John Michael Kapp after whom the case is known, set their gill nets during the 24-hour window in protest. Each held a commercial licence to fish in the area, but could not fish until August 20th. The DFO laid charges.

In their defence, the commercial fishers argued that the early opening for the Musqueam, Tsawwassen and Burrard created a "race-based" fishery or a "segregated" fishery based on a "racial classification system" that violated the equality guarantees in the constitution.

In five separate but concurring opinions, the justices in the BCCA rejected this argument, and rightly so. But they were not as clear in rejecting the race-based characterization of the fishery as they should have been. That charge still reverberates in the aftermath of the decision.

Although the pilot sales program was not without problems, and it is difficult to discern whether it contributed to the stability of the fishery or increased the conflict and animosity on the water, the characterization of the fisheries as "race-based" is wrong.

'As they had done for centuries'

Aboriginal rights are not based on race, but, as the Supreme Court of Canada has indicated in another fishing rights case, on the fact that "when Europeans arrived in North America, aboriginal peoples were already here, living in communities on the land, and participating in distinctive cultures, as they had done for centuries."

The source of an aboriginal right to fish, therefore, lies not in a racial designation, but rather in the use and management of the fisheries by distinct political communities whose existence long preceded the British assertion of sovereignty.

The Supreme Court has recognized a constitutional right of aboriginal peoples to a food, social and ceremonial fishery. In one instance it has also recognized an aboriginal right to a commercial fishery. In doing so, the Supreme Court noted that the constitutional entrenchment of aboriginal rights provides a means by which to reconcile the prior aboriginal presence with Crown sovereignty.

A small step

In R. v. Kapp the commercial fleet argued that Canadian courts have not recognized an aboriginal right to a commercial fishery for the Musqueam, Tsawwassen or Burrard, and therefore that there is no constitutional basis for their prior access to the fishery. This is true, but then no court has denied this right to these First Nations either.

Aboriginal rights to fish were not the issue in this case, but they are the subject of continuing treaty negotiation, and may form the subject of litigation should the negotiation prove unsuccessful.

In the absence of a definitive court ruling or treaty settlement, the pilot sales agreements were an attempt to forge a partial reconciliation between Crown sovereignty and the prior aboriginal interest in the fishery. They did not create "race-based" fisheries; instead the agreements were the product of growing recognition of aboriginal rights to fish, and that these rights would, in some cases, include rights to commercial fisheries.

If there is an equality issue in the management of the fisheries, it lies not in the 24-hour exclusion of the commercial fleet, but rather in the failure of the Canadian government over the past century to recognize and protect aboriginal rights in the fishery. The pilot sales agreements were a small step in that direction.

Douglas Harris is an assistant professor in the Faculty of Law at the University of British Columbia. He is the author of Fish, Law, and Colonialism: The Legal Capture of Salmon in British Columbia. ![]()

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: