[Editor’s note: In conjunction with this story, The Tyee is offering 100 copies of the spectacular exhibition catalogue Kites, Guns & Dreams, featuring images of Afghanistan by Grabowski and three other Canadian photographers. Copies are available to new Tyee subscribers who send their name, e-mail and mailing address to [email protected]. Information will be used only for the purpose of this promotion.]

Three girls, Fatana, Shogofa and Nargis, are co-workers in the eggplant field on the outskirts of Kabul. They start work before sunrise. In the summer, they finish usually around 10 a.m., when it gets too hot to continue. They drink water from the roadside pump and head off to school, about five kilometers away in the Shash Durak district.

The class gathers slowly at the Aschiana Centre, a dilapidated brick building covered with layers of faded yellow paint. By noon most students have arrived and are preparing for a calligraphy lesson with the school headmaster, Mr. Atiq. It is a very disciplined class. The silence is broken only by the scratching of sharpened sticks dipped in black ink with which the children draw the round letters of the Dari alphabet on scraps of recycled paper.

Aschiana means “nest” in the Dari language. It responds to the post-war reality of the Afghan capital — an army of working street children whose days are devoted to basic survival. Most of them are missing one or both parents, and many live with distant relatives. They are too busy to go to regular school and can only attend classes if they are sure that they will not lose their meager incomes and go hungry, or without warm clothes in winter.

Circus skills, butterflies

Aschiana is an Afghan non-governmental organization working in partnership with Terre des Hommes, a Geneva-based group devoted to helping children around the world. Once in a while, other organizations help as well, such as Canadian International Development Agency, which provided financing to train the Afghan staff. In its six drop-in centres in Kabul, Aschiana currently takes care of about 2,600 girls and boys between the ages of six and 16—a small percentage of the working street kids in the city, estimated by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees to number 28,000.

Aschiana is not a regular school by any means. One can attend classes at any time, before or after work, and the centre provides one simple meal each day. Besides literacy and math, the curriculum includes basic knowledge about different types of mines and other unexploded ammunition.

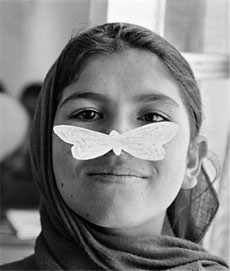

Occasionally, volunteers from various countries come and teach new, unpredictable subjects. Camilla Barry, a San Francisco area science teacher, appeared one day with a wonderfully funny method of teaching physics by such means as balancing cardboard butterflies on kids’ noses. On another day, Nick Putz, a circus arts teacher from London, led a workshop on juggling, clowning and other circus skills.

Tiny niches, hopeful faces

I took a picture of the class with Mr. Atiq and spent the next week following some of his students to work.

I went with Jamshidi and Faheem to the bazaar where they sell plastic bags; with Azmarai to his job selling water at the bus stop; with Naweed to the pond of sewage water where he washes cars; with Khanwali to the spot downtown where he panhandles alongside his father, who is missing both legs; with Mujtaba, who extracts from the ruins of the city combustible fragments that her family uses for cooking; with Shakib to his shoe-polishing stand in front of a government ministry; with Haroon, who burns incense in front of restaurants and vendors’ stalls.

All of these children have their tiny niches in the city’s economy. Some jobs are little more than excuses for begging, but they are socially accepted and they make a difference to the survival of entire families. Despite the incredible damage done to the city and its people, in Kabul there are no homeless, dispossessed children as there are in other cities in the developing world. There is, however, grinding poverty and semi-homelessness of whole families, who live in ruins and shacks and who have virtually no income.

Many of the children at Aschianaare too small for their age; all are too mature for their years. They are reliable and smart but bruised by various traumas. Some have little life experience beyond being war-zone kids.

Aschiana provides an environment where they find rudimentary self-esteem and the chance to dream of a happier future. In their lives there is little time to play, except on rare occasions when somebody like Camilla Barry or Nick Putz passes through. The kids crave knowledge and attention and accept these as gifts.

In return, they can only offer their curiosity—a fair exchange.

Christopher Grabowski is a widely published, award-winning photojournalist whose images were part of the Kites, Guns & Dreams Fisheye featured by The Tyee last October.

Further Reading:

Terre des Hommes

Aschiana Center

Care Canada

Street-working Children Report

![]()

Read more: Photo Essays

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: