Pity poor Grim Jim.

Last year Canada's former environment minister, Jim Prentice, happily seized the helm of Alberta's petrostate, a Soviet-like vessel ruled by one party for 43 years.

After replacing his disastrously entitled predecessor (the millionaire lawyer Alison Redford), the corporate banker expected clear sailing, if not an obedient and grateful crew.

But Prentice forgot about oil prices.

As political scientist Terry Lynn Karl has long argued, governments that depend on revenue from hydrocarbons (30 per cent of provincial government income) can quickly become unstable when that revenue collapses. Oil is, after all, the world's most volatile commodity.

When prices tumble, every authoritarian quirk of the petrostate, including incompetent statecraft, over-centralization, cronyism and unrepresentative taxation become as naked as summer bathers even to the most distracted voter.

Periods of low oil prices, writes Karl, "may be the only opportunity to move petrostates from vicious development cycles to virtuous ones."

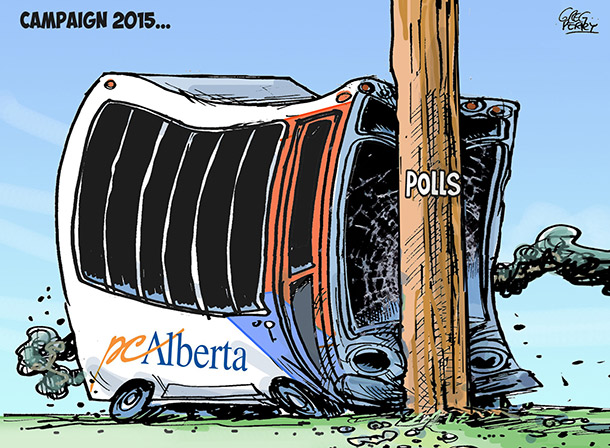

That potent observation goes a long way in explaining the declining fortunes of Grim Jim and his Progressive Conservatives, as both the Wildrose Party and New Democrats now surge in popularity before Tuesday's election.

Unpopularity no accident

You can't say that Grim Jim didn't try. As oil prices collapsed, he realized that having a strong political opposition in the guise of the right-wing Wildrose Party might be a significant disability.

So in a masterful display of Machiavellian sentiment, Prentice convinced the majority of that party, including its leader Danielle Smith, to cross the floor and dine under the tent of the one-party state. Albertans were appalled by the undemocratic power grab.

Ever since then things have gone from bad to worse for Grim Jim, says Paul McLoughlin, one of the province's most astute political analysts and editor of Alberta Political Scan, a weekly newsletter.

Prentice's growing unpopularity is really no accident. Albertans have a hankering for populist premiers, explains McLoughlin, and Prentice's slick "corporate banking image lacks appeal outside of Calgary."

The former banker also seems touched by the arrogance of Marie Antoinette. Last March, he told a CBC phone-in show: "In terms of who is responsible [for the Alberta government's current financial situation], we all need only look in the mirror. It's basically all of us have had the best of everything and have not had to pay for what it costs."

Blaming Albertans for the serial incompetence of the government didn't go over well. "His popularity took a big drop after that," says McLoughlin, and it is now reaching the muddy lows of Redford.

Then came the budget, a repeat of previous Tory foibles. It delivered chronic deficits for the province with no long-term solution in sight other than praying for higher oil prices.

Grim Jim not only failed to address the issue of low royalties, but also did nothing about Alberta's petrified taxation system. Like many petrostates, the government has long abused hydrocarbon revenue to lower taxes over the years.

Karl explains this particular petro-curse well: "Generally, oil rents produce a rentier state -- one that lives from the profits of oil rather than the extraction of a surplus from its own population."

In fact, Alberta's unrepresentative tax system has authored much of the province's fiscal grief, reports Queen's University law professor Kathleen Lahey.

"In moving to a single corporate and personal income tax regime, the government has walked away from at least $6 billion in annual revenues -- roughly the size of the forecasted deficit for next year -- and actually increased the tax burden for those income-earners at the bottom end of the scale, who are predominantly women," writes Lahey.

Albertans, adds McLoughlin, have never been big fans of inequality, and low oil prices have now dropped the curtain on the Tories' dismal tax policy that cultivated inequality.

Luck and circumstance

And then along came Rachel Notley. The Edmonton lawyer actually believes in transparent government, fair taxation and a legislature that represents ordinary citizens as opposed to pipeline companies.

But to McLoughlin, the surge in NDP support in the polls is probably "more a reflection of anti-PC sentiment in the province that has been growing since revelations about the government in the Alison Redford era."

These revelations build a staggering portrait of unaccountability and negligence. Alberta Health Services, for example, spent $3 million just relocating staff around the province between 2011 and 2014. And then there is the 2009 Alberta royalty blunder that has cost the province more than $2 billion in revenue a year or a staggering total of $13.5 billion.

To round things off, former provincial Tory minister Ted Morton wrote a scathing paper about the highly secretive and backroom decision-making that has typified Alberta's one-party state for decades. Another former Tory minister raised the corporate tax giveaway as problem, too.

Politics, says McLoughlin, is often about luck and circumstance, and low oil prices have delivered both.

"The NDP changed leaders at just the right time. They offer an appealing leader whose articulated outrage has resonated with the public as a credible alternative to a tired political class in the province."

Adds McLoughlin: "If Rachel Notley and the NDP win the election, for the first time in two generations the oil and gas companies operating in Alberta likely will face a policy pushback from its citizens."

That would be a virtuous turn for Alberta.

In petrostates, "economic and political power is especially concentrated," explains Karl, and "the lines between public and private are very blurred."

Low oil prices have not only exposed this dysfunction, but also made it impossible for Grim Jim to do what petrostates have always done best: buy consensus and co-opt dissident voices. ![]()

Read more: Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: