Natural gas made its debut in the City of Vancouver over a century ago, where it started out in things like lamps, then crept beneath ground into a network of pipes tracing the city’s main thoroughfares, and then eventually across the province.

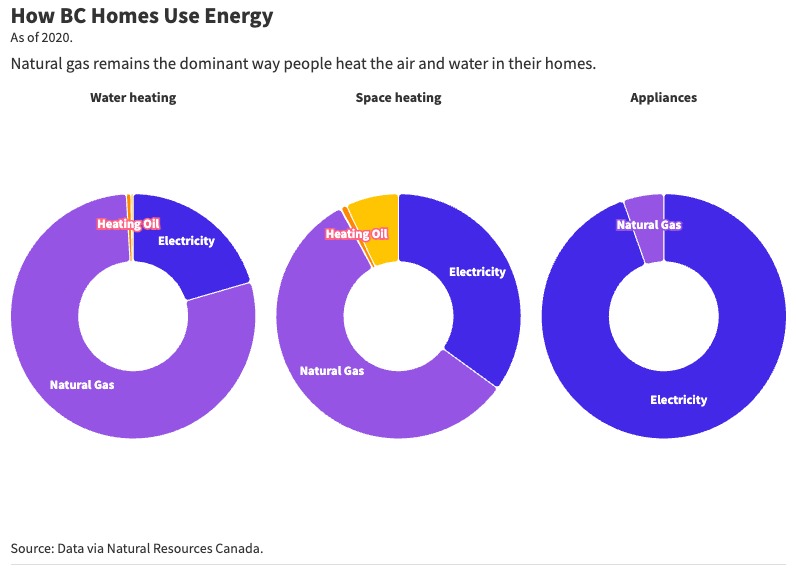

Today, it’s the primary way B.C. powers its buildings, and a major problem for B.C.’s pursuit to cut its emissions by 40 per cent in a mere six years.

But in some places, a change has begun.

“We are seeing a very significant shift away from gas systems,” said Mark Bernhardt, founder of Bernhardt Contracting, an energy advising company for small residential and large buildings based in Victoria. Electricity, he said, is starting to take its place, particularly in the southern parts of the province.

“It’s relatively cheap to install, it’s very cheap to maintain and it works,” Bernhardt said.

In Vancouver, 25 per cent of new commercial and multi-family residential buildings are now being built without gas hookups.

The city credits the turn to electricity in part with new municipal building rules that incentivize builders who install low-carbon systems that eschew broad use of fossil gas.

Historically, the province has been reticent to bring a regulatory hammer to curb gas where it flows inside buildings and factories. But this year, it announced its first emissions standard for new residential buildings, the Zero Carbon Step Code. By 2030 or so, when the highest “step” of the code is mandatory, Bernhardt says it will effectively bar the construction of new buildings running primarily on fossil gas.

For 14 municipalities covering 20 per cent of B.C.’s population, that reality is coming even sooner — they voted to bring the highest step in early.

That puts B.C.’s biggest gas utility, FortisBC, in a major bind.

To circumvent the coming regulatory hammer, Fortis hatched a plan to guarantee all new buildings a lifetime supply of renewable-branded gas, squeaking through local government’s new laws.

Last week, the BC Utilities Commission, or BCUC, rejected that plan. But the ruling doesn’t necessarily mean Fortis’s gas is out of the picture for B.C.

On the same day it issued its rejection, the utilities commission approved Fortis’s big-picture plan to supply its future demand — which the company anticipates will increase. To address B.C.’s climate targets, Fortis said it will swap out three-quarters of its fossil gas supply for what it calls “low-carbon gases” like renewable natural gas and hydrogen by 2050.

“We are reviewing these decisions and will provide an update in the coming weeks on what they mean for our customers and the timelines to implement,” said FortisBC in a statement.

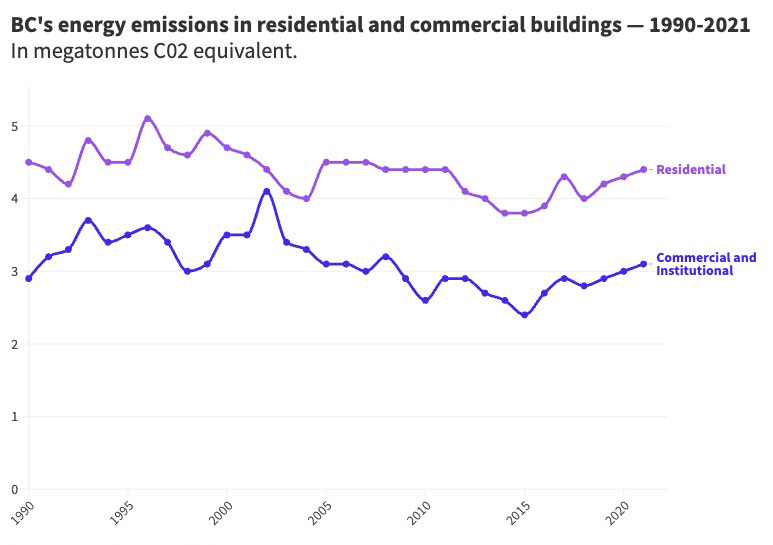

For now, Fortis’s pipelines continue to be filled with mostly fossil gas, and that’s a problem for B.C.’s climate commitments. Over the last three years, instead of working towards the target of almost halving gas utilities’ emissions by 2030, residential building emissions rose eight per cent and commercial and institutional buildings rose 13 per cent.

In the first two instalments of this series, Tyee investigated the potential emissions impacts of renewable natural gas from the plant to the burner tip, and critical questions around supply of the limited resource.

And in a related news story last week The Tyee reported on the BCUC’s decision to reject BC Fortis’s proposal to pledge, by a complex definition, that renewable natural gas would be supplied to all new residences, the extra cost subsidized by all customers.

In today’s final chapter, we ask the bigger questions: what future is there for gas, whether it comes from garbage or fossil fuels, in B.C.’s future energy supply? And what will it take for B.C. to crack down on rising building emissions?

The Zero Carbon Step Code

Until the Zero Carbon Step Code was adopted, municipalities had few regulatory tools at their disposal to curb building emissions.

They made do with a similarly named standard, the BC Energy Step Code, that instead allowed them to encourage things like thick insulation and sturdy windows. Under the BC Energy Step Code municipalities couldn’t, however, control the emissions buildings create.

For the past three years, the City of Vancouver, City of North Vancouver and other municipalities devised a workaround: they gave builders a choice between the efficiency-focused rules, or a set of bespoke standards that target emissions. The low-carbon option tended to win out relative to the efficiency option, says Bernhardt, because it’s generally cheaper to go electric than to use high-efficiency building materials. That workaround had a substantial impact — Vancouver's drop in new gas hookups happened after the rule came in.

“There is definitely a trend, which can be attributable to our carbon limits in the Vancouver Building Bylaw,” a representative from the city’s green and resilient building team confirmed to The Tyee via email.

Seeing the speedbumps ahead, FortisBC applied to the BC Utilities Commission for their own workaround.

“It is expected that municipalities with policies like North Vancouver and Vancouver will see very few new residential gas attachments” as a result of their new emissions targets, the company wrote in their 2021 application to the BC Utilities Commission, “unless there is a viable renewable gas solution.”

Fortis already had a voluntary renewable gas program available to any customer up for paying the extra money. But it was a short-term commitment: a home could opt in one month and opt out another. The company needed something more permanent.

So they crafted their now-rejected proposal promising that all new residential buildings would be fuelled with a lifetime supply of 100 per cent renewable natural gas at no added cost. Those new RNG-fuelled homes would also never pay carbon tax, and they’d pass within municipalities’ emissions rules.

As the utilities commission considered the ill-fated FortisBC pitch, B.C. raised the stakes of the endeavour, introducing the Zero Carbon Step Code. Even at its most stringent, this code won’t ban gas outright — fireplaces and patio heaters get a pass, for example — but it will stop builders from using gas-burning systems as their main energy source.

While the final step of the code will be mandatory in 2030, some municipalities have voted to bring it in sooner. Nanaimo, for example, launched a motion to implement it in full by July 1, 2024.

Fortis took action, attending “every single council meeting” as Nanaimo decided whether to implement the highest level of the new emissions step code this year, said Coun. Ben Geselbracht.

The company sent delegations to make a case for patience as FortisBC brings RNG online.

Their all-RNG buildings “will actually exceed the zero carbon step vote if approved,” Jason Wolfe, director energy solutions at FortisBC, told council last August.

After several tense meetings and a cross-border campaign linked to the Alberta United Conservative Party’s energy “war room" calling on the city to reject the step code, Nanaimo approved it anyway.

“It wouldn’t have gone through if it wasn’t for the organizing that’s been done at the grassroots level,” said Geselbracht.

For now, with the full provincewide implementation of the Zero Carbon Step Code at least six years away, Fortis’s access to most of B.C.’s new construction remains. But as more municipalities adopt it, its future becomes more uncertain.

Towards electrification in existing buildings

New buildings are among the least of B.C.’s climate problems, says Jeremy Caradonna, city councillor for Victoria.

“Eventually, we're going to have to face up to the realities of the fact that the lion's share of our emissions come from existing buildings, not new buildings,” he said.

These are the structures where sunk costs abound: gas-powered water heaters and furnaces can be expensive to replace, creating a dependence on maintaining already-installed gas systems.

But B.C. has made some inroads to break the pattern. Last December, government launched consultations to require new purchases of space and water heating equipment to be “100 per cent efficient” by 2030.

This would mean a property manager or homeowner faced with something like a broken gas furnace will have two choices: they could get it fixed or replace it with a more efficient option like an electric heat pump. While some gas options, like gas heat pumps, might squeak through the emissions rules, as they do not explicitly ban gas, current technology coupled with FortisBC’s current fossil gas supply effectively takes most gas options off the table.

“One of the gentlest ways to start getting gas out of existing buildings is to say that as your equipment hits end of life, you need to replace it,” said Liz McDowell, senior campaigns director for Stand.earth.

That gradual approach might be a nod to the scale of the challenge ahead.

“We can't just suddenly replace all of that natural gas with electricity,” said Jessica McIlroy, city councillor for the City of North Vancouver and manager of buildings at the Pembina Institute. “It’s a huge load.”

Besides powering over three-quarters of B.C.’s buildings, the gas system also has notable perks. Unlike the hydro-fuelled electricity system, gas provides a steady source of instantly dispatchable energy. It can be stored and used to top up power supply at times where lots of people need it — during the busy hours in the evening, for example, and in the coldest days of winter.

Electricity is less elastic, and the province needs to build out the electricity grid with enough power to weather those peaks in energy use. That’s particularly true for the province’s coldest regions, north of Prince George, said Bernhardt.

In an email, Fortis said its gas system is “critical to meeting peak energy demand, as we saw during the recent cold snap.”

“There are temperatures at which heat pumps don't work as well,” Bernhardt told The Tyee. Having a secondary gas or even diesel-powered system to turn on during the coldest periods is helpful in those limited scenarios. But for most of the province’s population, Bernhardt says electricity and heat pumps are more than capable.

If B.C. wants to more fully electrify, it faces a triple bind: to replace its reliance on fossil fuelled gas with electricity, it’ll need more of it. To decarbonize other largely fossil-powered parts of the economy, such as transportation, it’ll need more power for that too. And it will need to do this as climate change throws a wrench into hydro generation.

This year, B.C.’s hydro-dependent electricity system imported more electricity than it exported from U.S. and Alberta, thanks to extended drought conditions that left its dams and reservoirs emptier than usual. Power imported from the U.S. tends to be fuelled with more coal and gas than B.C.’s hydro-laden electricity grid, making it less climate-friendly.

Currently, less than eight per cent of B.C.’s electricity comes from non-hydro renewable energy like wind, solar and geothermal.

Development of those renewables in B.C. slowed to a trickle after the BC NDP cancelled its ongoing call for new power projects in 2018. That put hundreds of renewable projects in wind, solar and run-of-river hydro, many of them led by First Nations, on the shelf.

Last summer, BC Hydro did pull an about-face, circling back on its five-year energy plan to make a recalculation two years in.

“There have been indications of increased load as well as decreased supply, resulting in an earlier need for future resources,” it wrote in an update.

In June, BC Hydro made its first call to purchase new renewable electricity in over six years, with a focus on big renewable projects — particularly wind — located near the biggest population centres and energy draws.

BC Hydro has not yet indicated whether another call for power will follow.

But whether this new renewable electricity can fill the void remains to be seen. Much depends on how fast B.C. residents electrify their homes, vehicles and industries. Liquefied natural gas is another major wild card: LNG Canada’s first phase of a possible two will use gas for its energy-intensive processing needs. But B.C.’s new energy framework requires forthcoming LNG facilities to offer a “credible plan to be net-zero” by liquefying their gas with electricity.

If it’s approved, the second phase of LNG Canada would use 90 per cent of the power from the province’s new Site C dam alone. Four additional LNG projects are proposed for the province, which, if approved, would also draw huge amounts of electricity.

Adding more electricity to the grid is essential, said McIlroy, but it’s not the only tool at B.C.’s disposal. Efficient use of that power is the other half of the bargain. That could mean incentivizing people to charge their EVs or heat their water tanks at night when energy is in less demand, effectively using those technologies as a storage system for later.

Electrification in some of the trickiest situations — such as heavy-duty vehicles, industrial processes and homes in the coldest climates — might also mean using RNG, but more scrupulously, to provide supplementary systems that can turn on when electricity can’t cut it, McIlroy says.

But, she adds, in most of the province, new buildings that are relatively easy to electrify don’t require supplementary RNG.

Fortis points to B.C.’s incoming electricity shortage as one of the reasons a wholesale shift towards electricity is bad news.

“This is an approach that B.C. cannot afford,” said Fortis’s vice-president of Indigenous relations and regulatory affairs Doug Slater during a presentation to the Metro Vancouver Regional District.

Fortis has its own plan to cut pollution while keeping the gas lines flowing. The company’s “Clean Growth Pathway” projects a scenario where growing appetites for gas and electricity can coexist by supercharging its supply of “low-carbon gases” like renewable natural gas, hydrogen and syngas, a type of gas produced from non-fossil sources via thermal conversion.

During his presentation, Slater cited a host of studies on the cost impacts of those “low-carbon gases,” including one FortisBC funded and co-authored with the Institute for Energy Systems at the University of Victoria.

“In a nutshell these studies show that an electrification centric approach results in an infeasible and unaffordable build out of the electric system,” Slater said.

But the UVic study’s lead author framed the conclusion differently.

“The cost of the entire energy system can be cheaper in the renewable gas pathway, but it can also be cheaper in the electric pathway,” said Kevin Palmer-Wilson, a former postdoc at the institute. “It really depends on how much renewable gas is actually available.”

As discussed in part two of this series, some of Fortis’s biggest anticipated suppliers have not even applied for permits to begin building their projects. To get enough renewable gas supply, the study’s main scenario anticipated a blend of mostly hydrogen and a fraction of renewable natural gas, which is not currently deemed to be safe — more on that below.

Tyler Bryant, FortisBC’s strategic advisor for climate change and energy, was Palmer-Wilson’s co-author on the study. FOI documents uncovered by Stefan Labbé for Glacier Media linked Bryant to another study commissioned by FortisBC, the B.C. government and BC Bioenergy Association.

In emails, Bryant asked the author of that study to remove sections of it, including those that reflected poorly on the benefits of gas versus electricity.

Of a sentence that read, “in the moderate climate of southern and coastal B.C., electric heat pumps can achieve GHG reductions more effectively than renewable and low-carbon gases,” Bryant asked via email: “How did this make it into the report?”

“Frustrating how you guys are trying to expand the scope of this study,” he added. The sentence was left out of the final report.

That study’s author told Glacier Media that the material Bryant asked to have removed should not have appeared in the report in the first place, and said that the decision to omit it was determined by a joint steering committee.

Slater’s presentation to the City of Vancouver was one instance in Fortis’s wide-ranging campaign to promote the climate benefits of its renewable gases, including ads on YouTube, podcasts and TV.

This week, Stand.earth and B.C. residents Lori Goldman and Eddie Dearden launched a lawsuit against Fortis for greenwashing its gas products.

The lawsuit alleges that Fortis’s ads exaggerate claims about the RNG in its system and misrepresent aspects of the RNG it buys as a means to keep people connected to their still mostly fossil-fuel gas supply.

“There is a public interest issue with deceptive marketing,” said Andhra Azevedo, a lawyer for Ecojustice representing the plaintiffs.

In an emailed statement to The Tyee, FortisBC said it disagreed with the allegations contained in the claim, and asserted it had conducted itself at all times in accordance with its legal obligations.

“FortisBC takes climate change very seriously and is taking action to help B.C. meet its climate goals,” the statement continued. “FortisBC always works to protect the environment — whether by helping customers reduce their GHG emissions, progressing initiatives to lower our own operational GHG emissions or implementing new environmental protections.”

Fortis’s big plan to outgas electrification

Fortis claims there will be an “adequate supply” of renewable and low-carbon gases to meet demand while simultaneously exceeding B.C.’s climate targets.

It plans to lean on RNG as its leading green gas until 2030, when its new cast of gases like hydrogen and syngas will enter the scene.

But that’s far from a sure thing.

Part one in this series looked at RNG’s real emissions impacts, and part two looked at the uncertain question of RNG supply, showing that some of Fortis’s biggest suppliers have yet to acquire any permits.

Fortis’s other prospective low-carbon gases leave more questions unanswered.

In its recently approved long-term resource plan, Fortis said hydrogen gas will “play an increasingly significant role in decarbonizing the gas system.”

But whether that gas system will be ready for hydrogen is unclear.

Hydrogen is less energy-dense than regular gas, so putting it directly in a pipeline is “like watering down beer at the pub,” said Eoin Finn, co-founder of environmental organization My Sea to Sky and an intervenor in the BCUC’s hearing on the Fortis application.

To use hydrogen, operators increase the pressure in the pipe to get enough energy in. And that can be dangerous. Hydrogen’s tiny molecules can wear pipes down over time, sometimes even leaking through their steel walls.

“The pipes can only take so much,” Finn said.

In its plan, Fortis didn’t address requests to explain how it plans to navigate the safety challenges of hydrogen in B.C.’s pipes, but the company has said the pipeline problem is one of its “next steps” to figure out.

This year, Fortis, Enbridge Inc. and B.C.’s Ministry of Energy, Mines and Low Carbon Innovation announced a partnership to study how hydrogen “can be safely and reliably delivered using the province’s existing gas pipeline infrastructure.”

Hydrogen production requires substantial energy to power the extreme heat and pressurized steam needed to turn source materials into gas. Even if it’s made from renewable energy, the logic of turning those renewables into gas instead of using them for electricity wears thin, said Sara Hastings-Simon, associate professor at the University of Calgary.

“The question becomes, what's the benefit of doing that versus just using electricity directly?” Hastings-Simon asked.

A recent study hints that the utility will likely lean on blue hydrogen, which is created from fossil gas and steam and requires intensive carbon capture technology, which is still scarce and expensive.

The BC Utilities Commission provisionally accepted Fortis hydrogen plans, but “the panel considers that it is premature to say that hydrogen will be the ultimate solution to FEI’s GHG-reduction objectives,” it said.

Fortis also has plans to use syngas, likely to be produced from wood, to bolster its supply.

Syngas can’t be delivered into pipelines like RNG, but it can be used directly in some industrial facilities, like a lumber mill that uses wood-produced syngas to power a pulp mill next door, for example.

That’s a less wasteful option than the energy-intensive steps of converting syngas into RNG, as Fortis’s currently contracted projects, Bradam Hamilton, Bradam Napanee and REN Energy plan to do. But it also relies on a B.C. wood supply that faces its own pressures and uncertainties, and burning wood can be emissions-intensive.

And, although Fortis projects it can get 75 per cent of its future gas supply from these low-carbon gases by 2050, it has no clear plan for the remaining 25 per cent, which might foreseeably consist of regular fossil gas.

Fortis presented the Utilities Commission with other climate ideas, including investing in energy-efficient equipment to help customers burn less gas. It also pitched a scheme to get emissions credits for selling LNG to boats, vehicles and countries around the world, which the BC Utilities Commission rejected “due to uncertainty in the LNG market.”

On the whole, the commission found Fortis’s long-term resource plan “was a reasonable first step towards a low carbon future.”

“Although it is possible that Fortis will not meet 2030 GHG reduction requirements,” the commission added, “rejection of the entirety of the [long term resource plan] would likely preclude Fortis from ever reaching its objective.”

Planning for an uncertain future

Whether it comes through low-carbon gases, electricity, or both, decarbonizing B.C.’s energy supply will require major changes in the way the province gets and uses energy.

So far, B.C. has left the job of energy planning to its various utilities. Majors like Fortis and BC Hydro make their own projections about their future prospects and plan accordingly.

Peter Russell, director of sustainability and district energy at the City of Richmond, said that approach doesn’t cut it. “You’ve got a regulated utility operating in a policy void,” he said.

In that void, the two duelling utilities present their own visions of a future beset by climate change.

Fortis plans for gas demand, and BC Hydro plans for electricity. Each offers different scenarios of B.C.’s energy future while making few mentions of their counterpart.

“The utilities are submitting long-term energy plans in complete isolation of each other, with very different goals, and very different ways of looking at the future,” said McIlroy.

Fortis’s “diversified energy scenario,” which sets the compass for its planning, anticipates almost twice the amount of gas than would be required if B.C. were to substantially electrify its economy.

So far, the BC Utilities Commission, which signs off on utilities’ plans, has played an ambiguous role on climate.

According to the commission’s chair Mark Jaccard, it can assess the strength of utilities’ plans against climate rules B.C. has put in place, but not if those rules don’t exist yet.

“The big decisions about climate policy should be made by elected officials, not by people like me,” Jaccard told The Tyee.

In a staff report to the City of Richmond, Russell wrote that “an ongoing policy vacuum” in the B.C. government “is resulting in continued demand for gas and expansion of gas grids, without any clear and cost-effective pathway to decarbonize existing demand and infrastructure.”

For example, said Russell, B.C. has announced targets to cap emissions from gas utilities, but those targets aren’t yet legally required — meaning Fortis doesn’t technically need to meet them.

On energy planning, Russell said B.C. has fallen behind. California’s utility commission, for example, does a comprehensive review of new gas infrastructure investments to avoid building out “stranded assets.” Denmark’s government has long engaged in “heat mapping” to assess buildings’ needs for power and to strategize the best way to source it. That practice helps governments plan and direct investment to things like energy storage and circular district energy systems to reduce power demand.

In B.C., Russell said that planning could also mean strategically allocating potentially scarce resources, like renewable natural gas, to the places that need it most, like industrial processes that are hardest to electrify.

B.C. has signalled an openness to that approach with its nascent climate-aligned energy framework, due in 2024, which could provide B.C.’s first overarching energy vision under climate change.

In its approval of Fortis’s long-term plan, the BC Utilities Commission hinted that the company’s next plan, due in 2026, might not get off so easy.

“[Fortis] will need to demonstrate greater sophistication in modelling how its demand may be affected by the energy transition and provide more detailed support for its planned actions to address GHG emission reductions,” it said.

Stand.earth’s Liz McDowell sees Fortis’s current window as a time for some soul-searching.

“What is the future of a primarily gas utility in a world where we’ll be heating fewer and fewer homes with gas in 10 years?

“If I was a Fortis investor, I might want to see what a transition plan looks like.” ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: