FortisBC has big plans for a future fuelled by renewable natural gas, and needs big new sources of gas to make those plans real.

In addition to promising to supply new residential customers solely with renewable-branded gas for their buildings’ lifetimes, the corporation says it will increase the amount of renewable natural gas flowing to existing customers throughout the province.

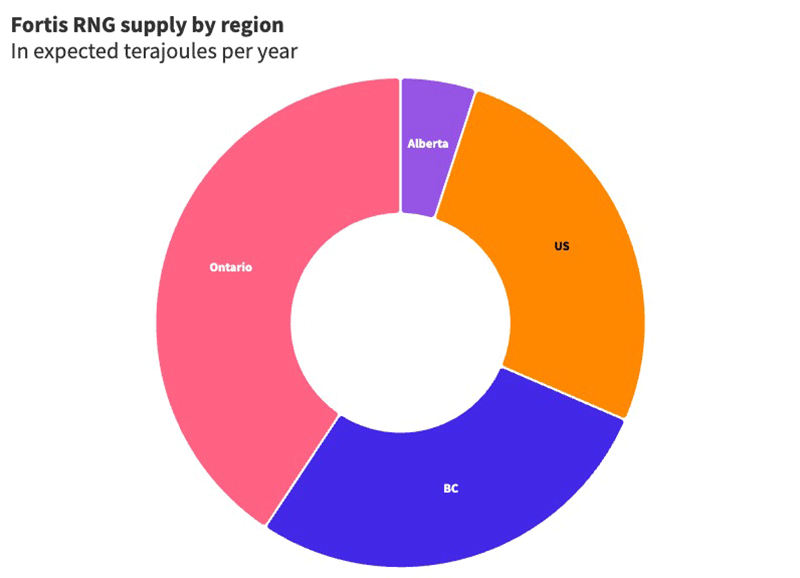

Renewable natural gas, which consists of methane captured from landfills or farms, makes up a tiny portion of FortisBC’s gas supply today, about one-half of one per cent. It comes from places like Seabreeze Dairy Farm in Delta and — indirectly — the Keystone landfill in Pennsylvania.

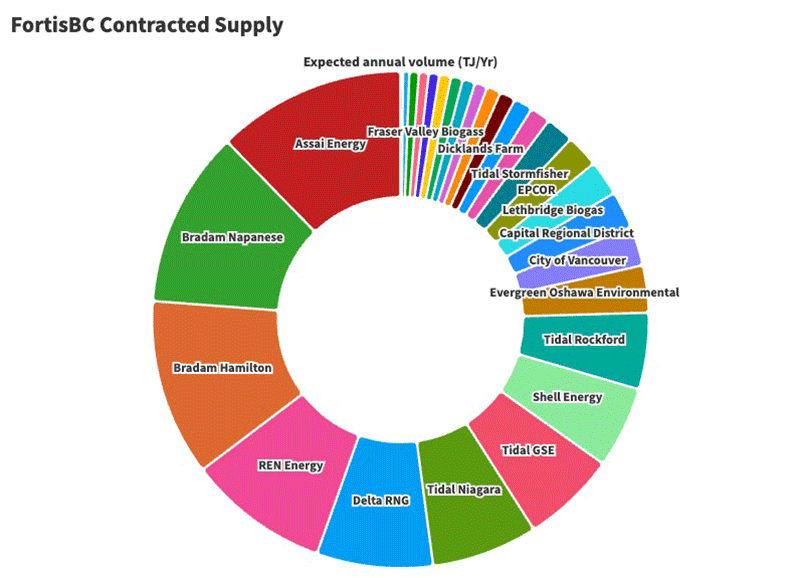

While the company says it currently has contracts to supply up to five per cent of the total natural gas in its system, last fall it told the province’s energy regulator it has about 40 per cent more than that, writing that its expected renewable natural gas supply “exceeds the output of BC Hydro’s Site C dam.”

But there are a lot of questions about the corporation’s “expected renewable natural gas supply.”

For example, the company Bradam Energies and its project Bradam Napanee, one of its largest expected suppliers, hasn’t even applied for the permits required to collect the Ontario town’s garbage.

“The Town of Greater Napanee is not aware of the proposed project,” a municipal representative told The Tyee via email. “No permit applications have been submitted.”

Bradam Energies LLC is Bradam Canada’s parent company. The Florida-based Bradam Energies was founded by John Finkbeiner, the former owner of a now-defunct biodiesel company found in 2018 to be leaking chemicals on an abandoned industrial site.

In FortisBC’s most recent disclosure to the BC Utilities Commission, it said it expected the Bradam Napanee project would already be supplying renewable natural gas. (Bradam being a small company with unproven technology.)

Fortis told the utilities commission that it expected its similar Bradam Hamilton project, using garbage from that city, would begin producing renewable natural gas last year.

But in 2019 Hamilton city councillors unanimously rejected the proposal and later signed a contract with another company to collect their waste until 2028.

Together, the renewable natural gas from these two proposed projects make up almost a quarter of the supply from FortisBC’s disclosed producers. The company continues to include Bradam’s future RNG supply in arguments it has enough RNG to carry out its plan.

Fortis’s promise to ramp up RNG faces big hurdles.

In Part One of this series The Tyee looked at the emissions impacts of renewable natural gas, examining its “carbon neutral” claims.

Today, we take a deep look into how Fortis is trying to source renewable natural gas in a competitive market with a limited supply.

“There are only so many landfills and so much food waste in the world,” said Sara Hastings-Simon, associate professor in the department of earth, energy and environment and the school of public policy at the University of Calgary. Unlike fossil fuel reserves, which tend to be vast and relatively scalable based on demand, RNG buyers like Fortis compete for a limited supply of gas from landfills, dairy farms and other suppliers.

“The sources for it are more limited,” Hastings-Simon said.

FortisBC declined an interview request from The Tyee. In an emailed statement, the company said that while the BC Utilities Commission had approved agreements with Bradam Canada Inc., “these are not yet operational and are therefore not part of our current supply.”

Fortis added that it has “has sufficient current RNG for many years of new construction activity in addition to other customer requirements.”

Betting on emerging technology

Bradam Energies' tenuous links to the planned host communities aren’t the company’s only problem. Its product is also experimental.

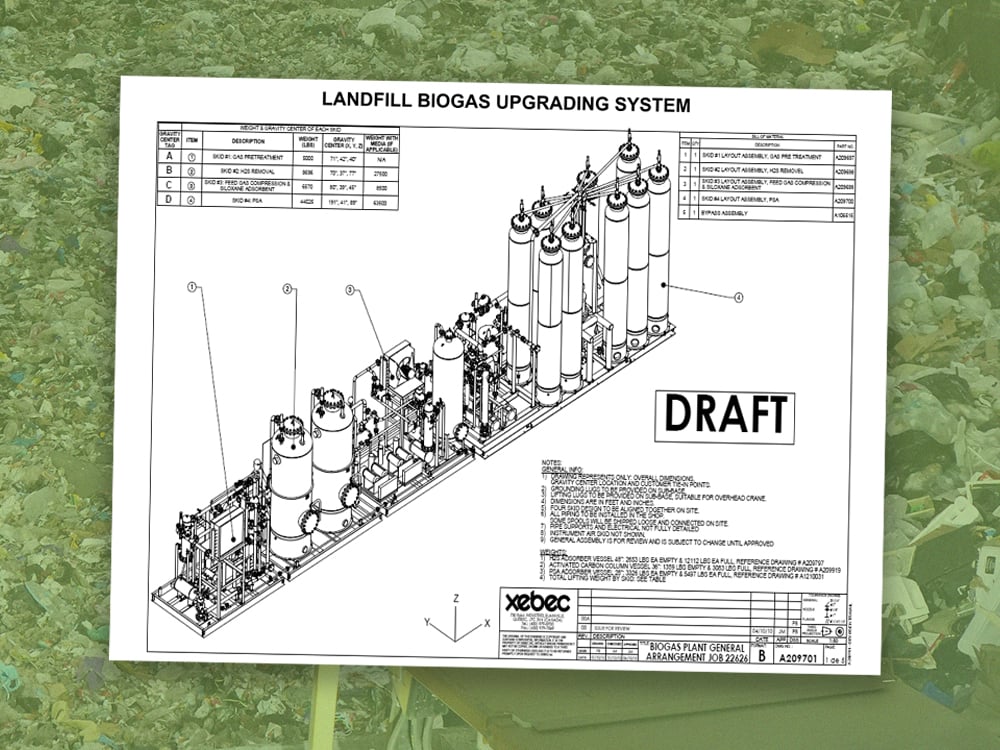

So far, commercially produced RNG comes from gases that emerge through anaerobic digestion, which happens in places like landfills and piles of manure.

But another class of emerging renewable natural gas technology, which Bradam is pursuing, doesn’t require that process.

“We take everything except metal and rocks,” said Mike Miscio, partner for Bradam Energies and president of AmaLaTerra, a company that proposed the project on Bradam’s behalf at a meeting of the Hamilton Public Works Committee in 2019. “We don’t discriminate.”

Bradam intends to use a process common in the fossil fuel industry, but novel for the production of renewable natural gas. It injects high-pressure steam at extremely hot temperatures, above 800 C, into waste, producing a mix of gases called “syngas” or synthesis gas.

That’s processed again with heat to produce pure methane for renewable natural gas. Energy is lost at each step of this process.

Bradam’s business model also relies on lots of garbage.

“My biggest concern here is that we’re basically making an excuse for unconstrained consumption,” Hamilton Coun. John-Paul Danko said during a 2019 council meeting where a delegation representing Bradam’s technology made a pitch to the city.

“These kinds of industries are classic greenwashing. We’re not solving the problem,” Danko added.

Fortis also has a supply contract with Bradam Napanee, a project aiming to use the same technology. Except, as noted, the town has never heard of the company nor its plans for waste.

In response to questions from The Tyee, the Ontario government confirmed that Bradam Energies has not submitted any applications through the province for projects, including Bradam Hamilton and Bradam Napanee.

FortisBC has not been forthcoming with details about its expected RNG supply.

It told The Tyee by email that the list of contracted RNG suppliers it submitted to the BC Utilities Commission inquiry is “dated.”

But Fortis refused to provide updated information. It pointed to a webpage listing current and coming suppliers, which does not include Bradam Hamilton or Bradam Napanee.

“You should refer to this list as the list changes,” a Fortis representative said via email.

But Fortis included anticipated RNG from both projects in its final submission to the BC Utilities Commission.

According to its last detailed disclosure of contracted RNG suppliers, the remainder of FortisBC’s supply comes in large part from Archaea Energy, a landfill project based in Pennsylvania. That includes its largest project, Assai Energy, the Pennsylvania landfill project owned by BP, formerly British Petroleum.

FortisBC’s fourth largest contracted supplier on that list is REN Energy, another project that plans to use not-yet-commercially used technology similar to Bradam’s high-steam, high-heat process to produce RNG through syngas. But they plan to use wood.

The company, whose executive chair is FortisBC’s former CEO, John Walker, stated last year that it plans to be FortisBC’s single largest supplier of RNG by 2030.

Like Bradam, REN’s product would also be converted into syngas and then into RNG, losing about half the initial energy stored in the wood in the process.

REN states that it plans to use waste wood to create its RNG. But research on non-RNG wood biomass plants in B.C. have found evidence that companies sometimes cut whole, previously live trees.

And, like Bradam Energies, REN's technology is still untested at a commercial scale.

RNG gets popular

Beyond its existing contracts, Fortis’s prospects of buying lots of cheap, plentiful RNG from elsewhere appear slim.

Fortis got an early start on the renewable natural gas game and was the first utility to offer RNG to its customers in 2011.

But now it has competition. Utilities in Quebec, New York, Nevada, Massachusetts and Washington state have pitched RNG to their customers as a way to decarbonize. Shell recently purchased RNG producer Nature Energy Biogas A/S, which sells RNG credits to customers who want to decarbonize their fuel supply. Kinder Morgan purchased RNG company Kinetrex in 2021, and Enbridge bought over a billion dollars’ worth of landfill RNG projects last November.

“As the world ramps up its decarbonisation targets, more and more companies and sectors see the benefits of taking advantage of RNG,” said Vincent Morales, manager of legislative and regulatory affairs for the Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas. He was speaking to The Tyee from California, where the coalition’s annual conference was underway at a five-star hotel in Orange County, complete with trips for golf and dolphin watching and sponsored by companies like Enbridge, Shell and TC Energy.

Morales is optimistic that there are lots more RNG-producing gases to be captured. “We definitely haven't done half of it,” he said. “There's still a lot more.”

The International Energy Agency reports that 85 per cent of currently available biogas has yet to be turned into RNG in North America.

But that potential still doesn't add up to a fossil gas replacement. Natural Resources Canada found, for example, that RNG sourced nationally could supply 3.3 per cent of our natural gas supply. In the U.S., the McKinsey Institute anticipates a broader range between five and 20 per cent.

Morales acknowledges that RNG-producing gases are “a finite resource.”

“I don't want to be flippant about that,” he said.

But he said he sees a role for RNG regardless. “I think it's a climate tool, and we need to use all the tools in the toolbox to reach net zero,” he said.

The third and final instalment of this series, which will be published Friday, poses one key question: Is there a case for gas, renewable or not, when the province and many of its municipalities have signalled that the future is electric? ![]()

Read more: Energy, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: