Just after noon on August 4, 2023, a boisterous gaggle spilled out of the Nanaimo Law Courts. A handful of supporters surrounded climate activists Howard Breen and Melanie Murray and their lawyer Joey Doyle, celebrating after days of legal wrangling with B.C. Crown prosecutors. Final submissions were months away, and a verdict on Breen and Murray's guilt or innocence won’t be known until at least spring. Yet the activists believe they have already struck a blow for justice.

That moment last summer takes on growing importance as more B.C. activists face prosecution. The legal breakthrough clinched by Breen and Murray could also embolden activists across Canada to ratchet up pressure on governments.

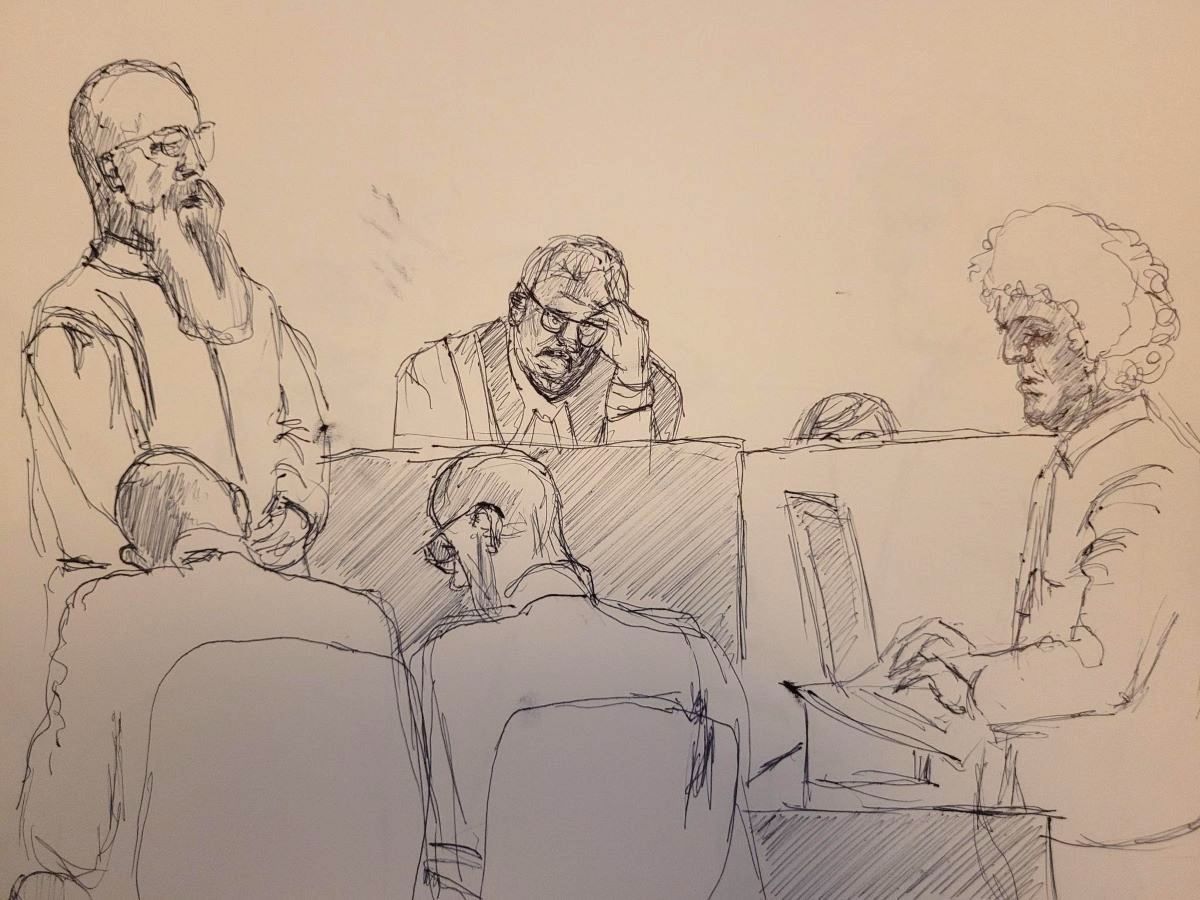

In those four days in a plain provincial courtroom, the judge broke precedent by allowing activists and their lawyer to mount their chosen defence for acts of civil disobedience committed by Breen and Murray: that the peril posed by climate disruption compelled their attention-seeking violations of law.

It’s called a defence of necessity, and it has a long history in the common-law traditions practised in many liberal democracies.

Canadian law has explicitly recognized the necessity defence for over half a century as an excuse for well-intentioned citizens breaking laws when circumstances left them no other choice.

In a 1984 Supreme Court of Canada decision that hinged directly on necessity, then-chief justice Robert George Brian Dickson illustrated defensible law-breaking by imagining a lost alpinist who's freezing and near death when they stumble upon a mountain cabin. Surely, reasoned Dickson, the alpinist must be forgiven for breaking and entering to save their life.

“At the heart of this defence is the perceived injustice of punishing violations of the law in circumstances in which the person had no other viable or reasonable choice available,” wrote Dickson.

Forty years of carbon emissions since Dickson conjured his hypothetical alpinist, Breen and Murray say that we are all alpinists — trapped in a storm of our own making. As Breen told the court: “We’re all in jeopardy because of climate inaction.”

Breen and Murray acted up in January 2022 in a series of highway blockades to garner media attention that would broadcast a message to the BC NDP government: Stop the clear cutting of the old-growth forests that excel at soaking up carbon dioxide and thus directly combat the growing threats from hurricanes, heat waves and wildfires.

Breen also faced charges for five more climate actions, such as disrupting log exports from the Port of Nanaimo by securing himself to a log boom with Gorilla Glue (which proved its advertised readiness “for the toughest jobs on planet Earth”). And closing the Nanaimo Airport by painting “Shut down runways to shut down runaway climate extinction” on the tarmac. And sealing the entrance to a branch of RBC, a global financier for fossil fuel developments, using more Gorilla Glue and a chain.

Admitting to breaking laws and pleading to be excused was a long shot with a potentially big payoff. Judges rarely entertain the defence of necessity in cases of civil disobedience. But when activists manage to mount the defence of necessity — the Canadian-first breakthrough that Doyle secured for Breen and Murray in Nanaimo Courtroom 227 — they frequently escape conviction.

What inspired a judge in a small provincial court to hear out this pair of climate activists and, in the process, give them yet another platform to broadcast their message?

Glued to a boom

Breen and Murray’s legal advance comes at a contested moment for climate activism. Direct action has grown into a crucial component of the global climate movement and delivered some big wins in Canada. Calculated disruptions such as Breen and Murray’s and mass arrests at the Fairy Creek logging blockades arguably prodded the B.C. government to finally start pulling the plug on old-growth logging. And direct action helped Quebec become, in 2022, the world’s first state or province to ban oil and gas development.

However, many governments are fighting back. There's a global trend toward criminalization of environmental protest. U.S. states have passed “critical infrastructure bills” that impose steep penalties and fines for activists who physically block oil and gas projects. B.C. and Canada stand out for extensive use of court injunctions to snuff out protests. Amnesty International and other human rights organizations have called out the use of injunctions to “undertake constant surveillance, harassment, and the forceful removal and jailing of Wet’suwet’en land defenders.”

The Crown is seeking 51 days of jail for Angela Davidson, a Da’naxda’xw/Awaetlala activist convicted last month of breaching an injunction and bail conditions during Fairy Creek blockades. Davidson is deputy leader for the Green Party of Canada.

At Breen and Murray’s trial, Crown attorneys made several stabs at painting them as potentially dangerous threats to society. As when Crown attorney Neal Bennet pushed Breen to comment on his severe bail conditions, including a $25,000 cash bond and in-home detention that lasted four months. Breen reminded Bennet that he had a hand in that, having told the judge, “'We haven't found weapons on Mr. Breen... yet.'”

Perhaps the Honourable Judge Ronald Lamperson didn’t care for the prosecutors’ disparagements of the accused. When Bennet persisted with the bail questions, Lamperson stepped in, warning the prosecutor against “prejudicial” questioning.

Or perhaps Lamperson was influenced by the handful of jurists in the United States, the United Kingdom and elsewhere who have allowed climate protesters to plead necessity in recent years.

Or maybe it was the weather. In the run-up to last August’s trial, Earth’s climate was shouting signals. Historic fires in Quebec blanketed Manhattan in smoke. Unprecedented warming smashed heat records around the world, unnerving climatologists as climate change suddenly seemed to outstrip projections.

Climate signals were not lost on Lamperson. “I read the news every day, including foreign news,” Lamperson told Breen when he was on the stand. “I don’t think you need to convince me that you have legitimate concerns.”

Last summer’s fires and heat helped defence attorney Doyle clear a crucial procedural hurdle in Nanaimo. To get his experts on the stand, and thus mount a convincing necessity defence, Doyle first had to show that the defence had an “air of reality” — that he had some semblance of a prayer of showing that the facts at hand met the strict conditions for court-sanctioned law-breaking.

Most attempts to use the necessity defence die on this procedural hill.

Leaping the legal hurdles

Criminal defendants today face the test for necessity laid down in that 1984 decision written by Chief Justice Dickson. The case, Perka v. the Queen, concerned smugglers who were motoring up to $7 million worth of cannabis from Colombia to Alaska when engine trouble and rough seas forced them to land near Tofino.

The smugglers argued they would have drowned if navigator William Francis Perka hadn’t steered them ashore, forcing them to bring illicit drugs into Canada. Dickson shut them down, based on a three-point test that remains little changed 40 years later.

Brutal, in-your-face climate disruption helped Doyle show he had a shot at meeting two of Dickson’s requirements: did Breen and Murray face “direct and immediate peril,” and did any harms they hoped to avoid through law-breaking outweigh the harms they caused.

As Murray told the court, “We’ve had highways shut for days because of flooding events, because of fires. People momentarily, safely blocking traffic is a very minor inconvenience when presented with what we know is coming.”

The third element of the Perka test was the tough one. To be excused for breaking the law, Dickson wrote, the accused must have had “no reasonable legal alternative.” Here, Doyle emphasized his clients' belief in direct action.

Breen and Murray had indicated on the stand that their actions were informed by the many historic advances won in large part through civil disobedience, such as the legalization of abortion in Canada and the landmark civil rights legislation of the 1950s and 1960s.

Breen told the court that his activism actually began after a Grade 8 school visit to Washington, D.C., in May 1968, one month after Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated. He saw blocks of burned-out shops and residences from the riots. “That had a profound effect on me,” said Breen. He joined Vietnam War protests the next year and continued with direct action throughout his life, protesting everything from apartheid in South Africa to Canadian production of missile components. He was once arrested for removing G.I. Joe dolls and toy tanks from a Toronto store shelf.

Doyle had an expert report on climate change and a world-renowned authority on civil disobedience waiting in the audience, ready to back up the reasonableness of his clients’ beliefs if only Lamperson would give them the chance. Doyle laboured for much of the trial’s third day making that case. Crown prosecutor Andrew McLean, a specialist dispatched from Victoria to defeat the necessity defence, lobbed one critique after another. Judge Lamperson repeatedly interrupted the relatively young defence attorney with questions.

The day ended in dramatic fashion with Lamperson’s surprise decision — an oral ruling that he seemed to craft as he spoke — that the modest provincial courtroom in Nanaimo would hear Canada's first climate necessity defence.

Morally involuntary

The highest hurdle to actually winning on the necessity defence may be a more philosophical question arising from Dickson’s 1984 decision — one that can only truly be answered by seeing inside the soul of the accused. The question is whether their action was morally involuntary.

Some form of the word "voluntary" appears 50 times in Dickson's text, where he calls the “moral involuntariness” of a defendant’s action the “essential criteria” for determining whether to excuse it. He borrowed his emphasis on involuntary action from American legal theorist George Fletcher and his musings on excuses.

In the 1978 book Rethinking Criminal Law, Fletcher described acts of necessity as a “compulsion of circumstance.” To prosecute in such cases is both useless and unjust. As Fletcher wrote, and Dickson quoted, “involuntary conduct cannot be deterred and therefore it is pointless and wasteful to punish involuntary actors.”

In Dickson’s formulation, what distinguishes acts of necessity from acts of the legally insane or helplessly intoxicated is the fact that they are morally unavoidable, as in the case of Dickson's hypothetical alpinist, who makes a conscious choice that the jurist considered to be involuntary. “His 'choice' to break the law is no true choice at all; it is remorselessly compelled by normal human instincts.”

It’s not an easy call. University of British Columbia professor Kimberley Brownlee, the expert that Doyle called to the stand in the trial’s final hours, critiqued the inherent ambiguity of Dickson’s approach in her 2012 book Conscience and Conviction: The Case for Civil Disobedience. Moral involuntariness, wrote the Canada Research Chair in ethics, “sits on the fence between a denial of responsibility because our will is overborne and an assertion of responsibility because, unlike physical compulsion, we will the act we take.”

As the Crown and defence jostled to control the narrative, the same acts were framed and reframed to fit one side or the other.

The 69-year-old Breen’s disobedience was hardly impulsive. He detailed decades of work for environmental non-profits and involvement with party politics, including several decades as an NDP member. The prosecution said this proved that Breen knew he had legal alternatives to effect policy change. To the defence, it gave him direct knowledge of the limits of democracy's legal options, which Breen exhausted before deciding that climate inaction drove him to violate laws.

Murray faced competing narratives for shifting choices in January 2022.

The Denman Island mother of four was new to environmental activism when she was first arrested on Jan. 17, 2022, blocking Highway 1 north of downtown Nanaimo. Before she next sat down on the Trans-Canada on Jan. 27, south of downtown, she was determined not to get locked up again. It was Murray who dropped the younger kids at the ferry in the morning to get to school.

Her choice to obey the RCMP orders that day seemed to fit the Crown’s assertion that her action was “voluntary,” and Lamperson seemed to agree. “It wasn’t a good day to be arrested and detained and held up. That answer suggests to me that... she made a conscious considered choice,” said Lamperson during the procedural debate, pushing back on Doyle.

Murray said her partner had emergency surgery on the 29th, so she was even less inclined to get arrested when she was back on the Trans-Canada two days later. But whereas three people were prepared to be arrested on Jan. 27, on the 31st Breen was on his own. This time RCMP officers had to carry Murray off the roadway in a plastic tarp.

Can a person make what Dickson would call a “true choice” one day and then have no true choice four days later? Murray seems to think so. “On the 31st I felt compelled to act,” she told The Tyee in August.

On the stand, Murray said she reneged on her agreement with the family that day in order to protect them. Breen also cited his obligations as a father and grandfather, his voice breaking during an emotional moment when he turned to his younger daughter in the gallery. “I need to be able to look at that sweet face over there and feel like I’ve done what I should have done for her and for future generations,” said Breen.

Reverend v. Oil Trains

As the Crown and defence lobbed arguments back and forth, the prosecutors deployed what could be a tie-breaking advantage: a precedent from B.C.’s highest court that cast a jaundiced eye on any use of the necessity defence for acts of civil disobedience.

The 2020 Trans Mountain decision involved activists who had trespassed on sites in Burnaby where construction was underway to expand the eponymous pipeline (which appears likely to start filling tankers with diluted bitumen in the coming months). The activists deliberately violated a court injunction protecting the sites, and a trial judge denied them the necessity defence, finding it unsupported by the facts at hand.

Siding with the judge, the Court of Appeal for British Columbia suggested that “planned protest activity” was unlikely to ever support a necessity defence. “The planned public defiance of a court order... in furtherance of an individual or societal goal, no matter how altruistic or serious that goal may be, is much more akin to a 'choice' than to morally involuntary behaviour.”

Furthermore, the court ruled that even if climate change was imminent and catastrophic, the defendants “could have chosen to do nothing and let the process unfold.”

David Gooderham, a retired litigation attorney and one of the activists convicted in Trans Mountain, says the decision marks a “stark contrast” with Justice Dickson's “deep probing” of what it meant to have choice. “The concept of ‘involuntariness' enunciated by Dickson somehow got lost” from provincial case law, said Gooderham.

But look beyond B.C., and courts’ treatment of climate change and the necessity defence has been moving in the other direction, especially since 2020.

Nowhere has the legal ground shifted as dramatically as just across B.C.’s southern border.

Five months before the B.C. high court’s hardline decision, a Washington state appeals court had delivered an equally definitive rejection of climate activists’ bid for the necessity defence. A 76-year-old retired reverend, George Taylor, had obstructed a train hauling crude oil through Spokane — on the grounds of both the climate and the risk of a devastating accident akin to the 2013 obliteration of downtown Lac-Mégantic.

When the judge overseeing Taylor’s trial decided to allow the necessity defence, the state ran to an appeals court, which overturned the ruling.

The appeals court ruled that there are “always reasonable legal alternatives to disobeying constitutional laws” and deemed all civil disobedience to be “objectionable and worthy of punishment.”

But that decision was short-lived. Barely one year later, the Supreme Court of the state of Washington smacked down the appellate court.

They delivered their decision eight days after the heat dome that descended on the Cascadia region in the summer of 2021, torching the B.C. interior town of Lytton, buckling roads and railways in Oregon and Washington, cooking roughly one billion creatures in the shallows of the Salish Sea and killing 600 people in British Columbia alone.

Washington state’s highest court noted Taylor’s numerous efforts to address the risk of oil trains by joining an environmental group, voting for pro-environment candidates, contacting elected officials and more. In spite of the legal “alternatives” Taylor tried, the oil trains kept rolling. The court thus deemed Taylor’s illegal action worthy of a necessity defence. “An alternative that has repeatedly failed... is not a reasonable alternative,” stated the court.

Their unanimous decision made Washington the first U.S. state to “affirmatively recognize the right of a climate protester to present the necessity defence at trial,” according to the Climate Defense Project, a U.S.-based non-profit.

Judges in Oregon, Minnesota, Massachusetts and the United Kingdom have also allowed a climate necessity defence to proceed. And, in most such cases, that defence set protesters free — via acquittals, hung juries or dropped prosecutions.

Taylor’s case was headed back to trial in the fall of 2021 when the railroad, BNSF, asked the prosecutor to drop all charges. No doubt the deterrent effect of a potential conviction no longer seemed worth the hits they’d take in the court of public opinion.

Cracks in the Crown

Final submissions for the Nanaimo case were set for December and then pushed back to this April. In the meantime, the climate picture continues to darken. It’s now known that last summer’s searing temperatures and record wildfires were part of the hottest year since modern measurement began in the mid-19th century, smashing the previous record. 2023 was also the first year in which Earth's surface was 1.5 C hotter than pre-industrial levels, reaching the Paris climate agreement’s red line for the end of the century.

Victoria lawyer Ben Isitt, who represents many of Fairy Creek's old-growth blockaders, says a decision favouring Breen and Murray will “provide a precedent for other citizens involved in climate-justice protests.”

Breen, Doyle and Gooderham say that whether Judge Lamperson acquits or convicts when he delivers verdicts later this year, the case will have advanced the necessity defence in Canada. Doyle says Lamperson’s decision will give activists insight into how they might tailor actions and arguments to “better fit into the defence.”

Breen is keen to share the trial’s expert testimony with environmental defendants so they can cite them in their own trials. “There’s a crack now that the light is shining through,” said Breen after the trial in August.

Gooderham sees another crack in a recent decision by Canada's Federal Court of Appeal citing global warming's “dramatic, rapidly unfolding effect on all Canadians.” In December the Federal Court of Appeal in Vancouver reinstated a lawsuit by young Canadians suing the federal government for climate inaction that imperils their future — a case that had no “prospect for success” in early 2021, according to the trial judge.

Might such "cracks" lead to anarchy if environmentally minded citizens feel increasingly free to break whatever laws they want in the face of steadily deepening climate disruption?

Crown prosecutor McLean evoked the threat of civic breakdown if civil disobedience and the necessity defence became commonplace. Look at the rioters storming the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, McLean told Brownlee during her cross-examination. Is that not a case of civil disobedience being used to democracy’s detriment?

Brownlee zapped back, flipping McLean’s argument on its head. The violent acts of Jan. 6, said Brownlee, could say nothing about civil disobedience because they don't fit the bill. As Brownlee succinctly replied: “They obviously lacked civility.”

In contrast, Breen and Murray's acts of civil disobedience clearly disrupted B.C. residents and businesses, but the evidence presented at trial showed that they were always calibrated and peaceful.

Brownlee told the court that such careful and constrained law-breaking strengthened rather than undermined democracy, which she illustrated via an iconic case of civil disobedience: American activist Rosa Parks choosing a seat at the front of the bus. As Brownlee put it in court: “When someone like Rosa Parks tests the constitutionality of a law, she isn’t flouting the rule of law; she’s supporting it.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Environment

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: