A B.C. company faces rare criminal charges 11 years after one of its employees was crushed to death on the job.

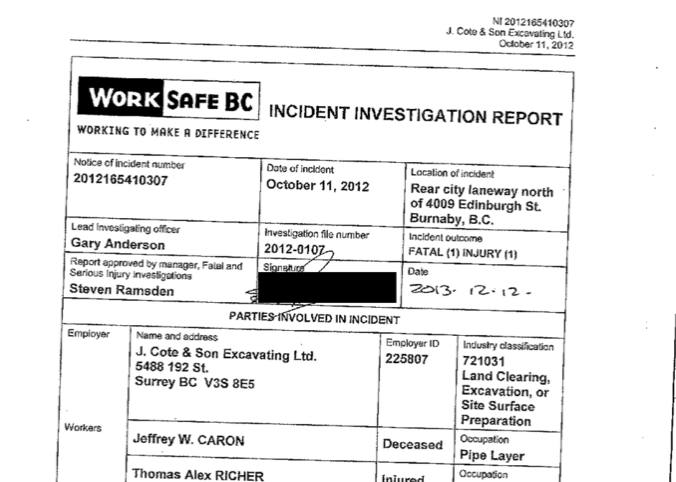

Crown prosecutors have charged J. Cote & Son Excavating Ltd. with criminal negligence causing death and criminal negligence causing injury in relation to the 2012 death of Jeff Caron, a pipe-layer who was killed while working on a project for the company in Burnaby.

It is a rare example of companies facing criminal charges related to the death of a worker.

One of Caron’s co-workers, Thomas Richer, was injured in the same accident.

The same charges were laid against David Green, the foreman at the site, who also faces an additional charge of manslaughter.

The charges are one of about two dozen cases in Canadian history of a company being charged with criminal negligence in the death of an employee.

The news was welcomed by Caron’s friends and family, some of whom had been calling for such charges for nearly a decade.

“Even back then, I remember saying, these things are often just swept under the rug and nothing actually happens,” said Travis Blanchard, a childhood friend of Caron.

“I’m really happy to hear something is happening and someone is being held accountable.”

Lawyers for the company and Green said they would plead not guilty.

Bill Smart, a high-profile defence lawyer, says J. Cote & Son “will not comment on the allegations other than to say that the company denies them, intends to plead not guilty, and intends to proceed to trial.”

Brock Martland, a lawyer representing Green, says his client “denies these charges in the strongest way possible.”

Martland said he expected the matter to proceed to trial, adding he was surprised charges were laid so longer after Caron’s death.

“It’s quite an extraordinary amount of time,” Martland said.

At the time, Caron was part of a team doing excavation work to replace a storm and sewer line in north Burnaby.

A concrete wall adjacent to the trench collapsed, pinning Caron. He would later die of his injuries.

A 2014 WorkSafeBC investigation found the wall had collapsed as a result of the company’s excavation. That report argued J. Cote & Son, the prime contractor on the project, had failed to assess the hazard posed by the wall.

The company responded that it had dug the trench according to an assessment provided by a professional engineer.

Richer told WorkSafeBC he had repeatedly expressed concerns to Green about the safety of the worksite, something Richer also repeated in comments to media at the time. Richer declined to be interviewed for this article, citing the ongoing court case.

WorkSafeBC did not issue penalties at the time and instead turned the information over to Burnaby RCMP in 2014.

When Caron died, Blanchard was part of a group of friends and family members who organized protests under the banner “Justice for Jeff.”

Blanchard grew up with Caron in Warman, a small city north of Saskatoon. Blanchard said he and Caron would spend afternoons listening to music and playing guitar in his bedroom — Metallica, Marilyn Manson and later softer rock music. Blanchard said Caron, who grew up in foster care, was almost part of the family. “He was the kind of guy who would give his shirt off his back for you. He always put a smile on everyone’s face the second he walked in,” Blanchard said.

Over time, Blanchard said, members of the “Justice for Jeff” movement lost touch. He said some feared the company would never be charged. Cindy Kahm, Caron’s biological mother, told CBC in 2014 she welcomed the criminal investigation.

Linda Gardipy, Caron’s aunt, said Kahm passed away about 18 months ago. Gardipy said she welcomes the charges.

“I feel good,” she said. “Somebody has got to be responsible for his death.”

Only a handful of firms and supervisors have been charged with criminal negligence causing death in Canada, and even fewer have been convicted.

“They’re just not common, period,” said Steven Bittle, a professor and criminologist at the University of Ottawa.

Bittle is a leading scholar on the Westray Bill, a 2004 bill that allows Crown prosecutors in Canada to hold companies criminally responsible when workers die on the job. The bill is named for the 1992 Nova Scotia mining disaster, which left 26 men dead.

But as of 2022, there had been only nine successful prosecutions under Westray, most of which resulted in fines. Only one person has served jail time as a result.

Bittle said that’s because criminal law in Canada is “hardwired” to deal with individuals.

“The criminal law does OK with those kinds of scenarios,” Bittle said. “What the criminal law doesn’t do well with is, why didn’t the individual feel they didn’t have the opportunity to shore up that wall? Were there decisions in the company that cut corners?”

For negligence to amount to criminality, Bittle said, prosecutors typically have to reach the bar of someone’s actions being a “marked” departure from what a reasonable person would do under the same circumstances.

When that logic is applied to a company, he said, it can be especially difficult to prove given the layers of supervisors, managers and employees involved.

Bittle said that’s why Westray charges are often only brought against smaller companies, like J. Cote & Son, which had about 20 employees as of 2014.

“It’s not hard to trace the chain of command as to who knew what, who should have done what and who had an obligation to do what,” Bittle said.

Bittle suggested the complexity of such cases may have contributed to the long investigation.

“The standard answer that you get is that they’re complicated cases. Police don’t always have the resources or the expertise to investigate them and it takes them a long time to do so,” Bittle said.

The United Steelworkers union has been advocating for tougher penalties for companies implicated in the deaths of workers. USW District 3 director Scott Lunny said he believes police and prosecutors should be applying the law more frequently.

“It’s not the goal to have lots of people go to jail. The goal is to have that as a realistic outcome if you’re not doing what you need to do as a company,” Lunny said. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: