Before Brian O’Donnell was prescribed the opioids hydromorphone and methadone by his doctor, he used cocaine, heroin and fentanyl to manage chronic pain from injuries he sustained earlier in life.

“If I didn’t have access to tested, safe drugs I’d probably be dead, just like a lot of my friends,” O’Donnell says.

O’Donnell, who lives in Vancouver, accesses British Columbia’s prescribed safer supply program, where clinicians prescribe pharmaceutical alternatives to illicit drugs in order to separate people from the dangerous illicit market.

It’s a program that users, doctors, advocates and researchers say saves lives, but it has also come under fire: Conservative Leader Pierre Poillievre recently introduced a motion in the House of Commons in May to end the program, saying it was fuelling addictions to opioids.

Poillievre’s motion, which did not pass, proposed redirecting money spent on safe supply programs to addiction treatment programs.

Dr. Caroline Ferris, a doctor who prescribes safe supply as part of addiction treatment, says safe supply programs should not be stopped. But Ferris said there are problems with the reliance on hydromorphone — also known by its brand name Dilaudid — in safer supply programs. She said hydromorphone doesn’t match the strength of fentanyl, the drug most opioid users are now addicted to, leading some to sell their prescriptions.

That in turn could be fuelling new opioid addictions, Ferris said. She said the studies that have been done of the program so far have focused on qualitative data — stories from people prescribed safe supply. “But we don't really have data to crunch and there's been a few problems with collecting that data for various reasons,” Ferris said.

Safer supply is designed to reduce harm, but experts are divided when it comes to weighing its pros and cons. Some experts worry access to pharmaceutical-grade drugs could encourage people to try drugs, or continue using drugs. Others say expanding safer supply reduces overdoses from illicit street drugs.

Bernie Pauly, a scientist with the Canadian Institute on Substance Use Research who has participated in evaluations of safer supply programs in Canada, says it’s clear that illicit fentanyl, not diverted safe supply, is killing people. She pointed to research by the BC Centre for Disease Control that found less than two per cent of illicit drug deaths in 2020 and 2021 involved hydromorphone with no fentanyl. Of those 45 deaths where no fentanyl was detected, there was an average of seven other substances in the person’s body. There were no deaths where only hydromorphone was detected.

Should we be concerned about diversion of safer supply?

Ferris says data collection on safe supply is in the early stages and individual anecdotes about young people using hydromorphone shouldn’t be discounted.

“We knew [Oxycontin] was out there before it hit the headlines, we knew fentanyl was out there long before it was declared a public health crisis — because we see people and we talk to them and we test the urine and we know what they're using,” she said.

While prescribed drugs are safer than drugs bought from the illicit supply because pharmaceutical drugs have a known potency and purity, they still carry a risk, Ferris says. If someone is buying diverted hydromorphone, for example, they may not know what dose of pill they are getting and for those who aren’t used to taking opioids, two tablets of eight milligrams of hydromorphone could be fatal.

“I'm not sure that it’s doing a favour for youth,” said Ferris, who says she knows of several teens under the age of 15 who recently died from suspected overdoses that included hydromorphone.

“If the person for whom it's prescribed is taking it, yes, it probably benefits them. But if they're diverting it, I think it's doing a lot of harm. And I think we have to acknowledge that diversion does occur.”

Data on youth drug toxicity deaths from the BC Coroners Service shows that between 2017 and 2022, there were 12 deaths in youth under 18 where hydromorphone was detected. One of the deaths happened in 2020, three occurred in 2021, and eight deaths were from 2022. In all of the deaths, at least one other substance that contributed to the death was found.

The data also shows that the vast majority of young people who died of drug toxicity used fentanyl: of the total 142 youth deaths between 2017 and 2022, fentanyl or its analogues were found in 112.

Not everyone agrees that diversion of hydromorphone is a problem. Garth Mullins, a drug user advocate who has been on methadone for 20 years, said he sometimes relies on diverted hydromorphone given to him by friends who have a prescription. Mullins said he takes hydromorphone when he’s having an off day and might be tempted to get drugs from the illicit market instead. He said many of the people he knows who have a hydromorphone prescription take a mix of hydromorphone and fentanyl because hydromorphone doesn’t completely replace fentanyl — but having the prescription allows them to use less illicit fentanyl.

Mullins said hydromorphone pills have always been sold on the street, but the cost has dropped dramatically over the years: from $10 a pill in the late 1990s to $1 a pill today.

It can also be hard to judge how much hydromorphone sold on the street has been diverted from prescribed safer supply programs. A B.C. government report said hydromorphone was dispensed 585,000 times to over 80,000 patients in 2018-19. That’s prior to introduction of the prescribed safer supply program in 2020, which Dr. Alexis Crabtree, a public health physician with the BC Centre for Disease Control, says around 5,000 patients — about 5 per cent of people who have been diagnosed with opioid use disorder in B.C. — have accessed so far.

Opioid use disorder is defined by the BC Centre on Substance Use as a chronic relapsing illness associated with high risk of death. It doesn’t matter if someone gets their opioids from their family doctor or an illicit dealer. People can get better if they can access treatment, the BCCSU adds.

Public health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry and B.C. chief coroner Lisa Lapointe have stressed all people with opioid use disorder are at risk of overdose if they use drugs from the illicit market.

What exactly is safe supply and how did we get here?

There’s a long history of successful prescribed safer supply pilot projects in B.C.

The 2008 North American Opiate Medication Initiative and 2011 Study to Assess Longer-term Opioid Maintenance Effectiveness found patients could benefit from access to doctors and opioids to treat severe opioid use disorder.

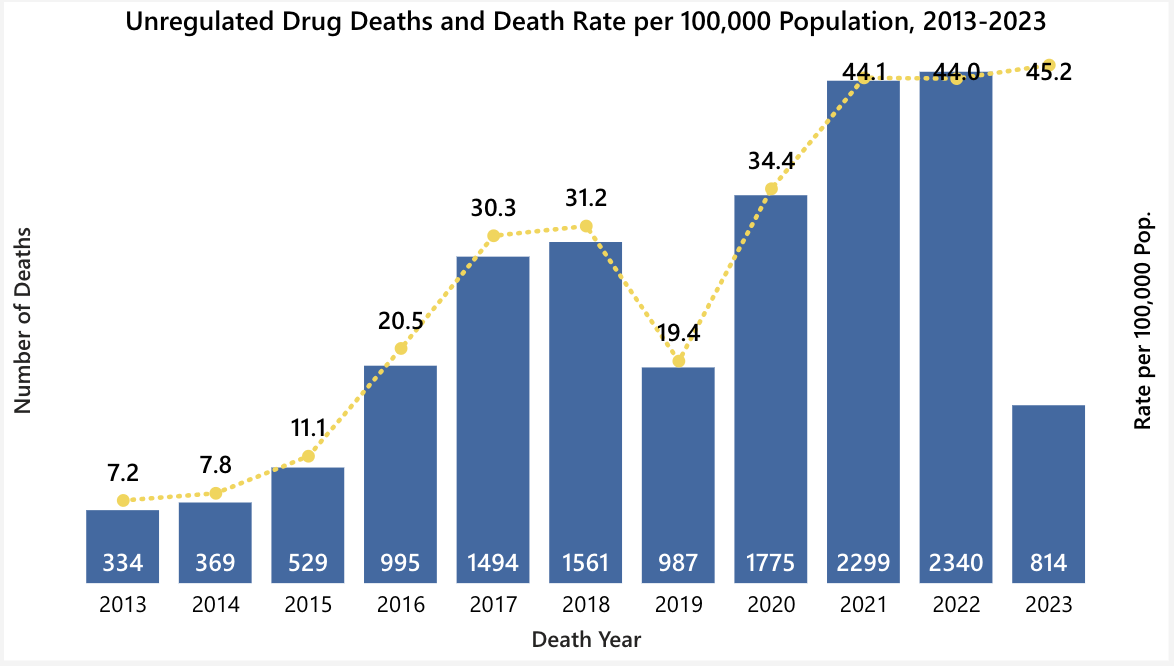

B.C. has been in a public health emergency since April 2016, when drug dealers in the illicit market started adding the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl to their supply.

This led to a spike in deaths from drug poisoning. Harm reduction initiatives like safe consumption sites, where people could take drugs while being supervised by health-care workers who would intervene if they overdosed, and naloxone distribution programs, which can temporarily reverse opioid overdoses, were successful in starting to lower the rate of death by 2019.

But in early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic erased any progress that had been made: closed borders and supply chain disruptions led to an unpredictable, and often deadly, supply of illicit drugs.

Around 200 people a month — more than six people a day — are currently losing their lives to toxic drugs in this province, the highest death rate ever recorded. Since 2013, 13,497 British Columbians have lost their lives due to unregulated drugs according to the BC Coroners Service.

In an effort to help people who use drugs isolate without going into withdrawal at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the BC Centre on Substance Use published “Interim Clinical Guidelines: Risk Mitigation in the Context of Dual Health Emergencies," which gave clinicians guidance on what they could prescribe as an alternative to toxic street drugs, including recommended doses.

Doctors have always been able to prescribe medication for pain, says Crabtree. These medications can include a family of drugs known as opioids, such as morphine, fentanyl, hydromorphone and heroin. If you’ve ever had a surgery you may have been prescribed an opioid for pain management — hydromorphone is very commonly prescribed for short-term pain, like knee surgery, or longer-term pain like pain associated with cancer, Crabtree says.

A year after the BCCDC published its guidelines, the provincial government introduced a policy that supported the guidelines and recommended prescribed safer supply as a way to reduce toxic drug deaths.

Under the provincial policy clinicians can prescribe fentanyl patches, fentanyl tablets, injectable hydromorphone, tablet hydromorphone and other opioids “as determined by programmes,” Crabtree says. These drugs are sourced from regulated pharmaceutical producers so clinicians and patients can know for certainty the dosage, potency and purity of the product.

The BCCSU guidelines also cover morphine, stimulants, benzodiazepines and alcohol withdrawal medication, she says. Clinicians are given guidance on dosages but ultimately choose what they should prescribe for their patient.

This policy allocated funding to the health authorities for prescribed safer supply, which they offered as part of a comprehensive addiction medicine program that also offered opioid agonist therapy and other treatments, Crabtree says.

Opioid agonist therapy is designed to treat opioid use disorder by giving people longer-lasting drugs that don’t provide a euphoric rush but do prevent people from experiencing withdrawal. It is different than prescribed safer supply which is designed to replace a person’s illicit drug supply.

Under the current policy, patients don’t have to pay for prescribed safer supply or opioid agonist therapy — they get it for free, similar to other drugs covered by the provincial Medical Services Plan. The policy also allowed clinicians not associated with health authorities, such as family doctors, to offer their patients prescribed safer supply.

Why hasn’t safer supply reduced drug deaths?

Safer supply was supposed to reduce overdose deaths, but the number of overdose deaths continue to rise — fuelling criticism that the program is misguided.

While safer supply programs have rolled out across the province the illicit drug supply continues to increase in potency and with added substances that can increase the risk of overdose, like benzodiazepines, which depress the central nervous system and can increase the risk that someone stops breathing during an overdose.

Supporters say the program does save lives, and works for those who can access it. They also point out that judging the program before it’s been scaled up — only 5,000 of B.C.’s 100,000 people with diagnosed opioid use disorder have accessed prescribed safer supply — is premature.

When a person wants to access safer supply, they start by talking with a doctor or nurse who will do a full assessment, including the person’s full history of substance use, current substance use, past diagnoses or treatment they’ve gone through and personal goals for their substance use, Crabtree says. This program is targeted at people with opioid use disorder.

What people are prescribed will be based on the assessment, but patients should also come in with an idea of what substances they take and at what potency they take them so they can ask for their prescription to replace that, Crabtree adds.

It’s important for prescribed safer supply to meet people where they’re at, says Guy Felicella, a peer clinical advisor with the BC Centre on Substance Use.

He says safer supply is about reducing how much people access the illicit market. For him, it’s still a win if someone accesses prescribed safer supply and the illicit market five times in a day rather than the 10 times they would have before their prescription. This is similar to a nicotine patch helping people reduce the number of cigarettes they smoke in a day, said Felicella.

To keep people away from the toxic street supply you need to provide the right substances and right potency to fully replace what they were taking before, Felicella says. Otherwise they’ll likely turn to the illicit market if they’re not getting their needs met by the prescription.

But that can be tricky for a number of reasons. First, someone might not know what they’re buying from the illicit market. Most street drugs look the same, taste the same and seem the same but can contain several different substances with wildly different potencies, Felicella says.

Second, prescribed safer supply needs to source drugs from regulated pharmaceutical manufacturers, and there just aren’t that many people making diacetylmorphine, also known as medical-grade heroin, Crabtree says.

The drugs that people can access through prescribed safer supply were chosen largely because they were what was available, she adds.

Where to go from here

None of the experts The Tyee spoke to are calling for the end of safe supply, but they all had ideas to improve and expand the program.

Ferris said addictions doctors are frustrated by the role of gatekeeping, and called for more non-prescribed models for safe supply. Crabtree echoed this.

“I think that [drug] prohibition should end and that people should be able to go buy whatever they want to get high on,” Ferris said, comparing the end of this prohibition to the end of prohibitions on alcohol and cannabis.

“If they're in a rural or remote area, it's really difficult to access safe supply,” Ferris adds. “So there's a terrible inequity about the availability of safe supply and there's a real fatigue on the part of prescribers.”

Crabtree advocates for a non-prescribed safer supply where people can access substances of known purity and potency, similar to how people currently access other psychoactive substances. She says she doesn’t know exactly what that would look like and couldn’t point to another jurisdiction with regulations like she’d want to see here, but added regulations would need to be much stronger than how alcohol or cannabis are controlled.

There’s no clear solution for how to avoid diversion. Doctors can require witnessed consumption or ask users of safer supply to take urine tests, but that creates barriers to access and can make drug users feel as though they’re being constantly policed.

When it comes to the concern about young people using hydromorphone, Mullins said young people have always experimented with drugs — in the 1980s, Mullins said, he went to a middle-class high school in Vancouver and had no problem getting heroin.

“I just think that kids need to know what's the difference between down that you buy on the street and dilly,” Mullins said. Dilly is the street name for hydromorphone and “down” refers to opioids.

“What's in the pill? What does it mean? What's an opiate? People need that good drug education. They need good support.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: