It was a hot Monday in early May, and Lisa Burns went to bed feeling optimistic. In response to flood warnings, she’d spent the day alongside neighbours hauling sandbags next to a rising creek along the back side of Falcon Road in Parker Cove, a small suburb near Vernon on reserve lands belonging to the Okanagan Indian Band.

“The creek wasn't high, and we had sandbags. And we're like, ‘Yep, we're good,’” Burns said.

At 5:30 in the morning, her husband woke her up. “He was like ‘Honey, you might want to get up and get dressed. There's a little bit of water on Falcon.’”

That water became a gushing current turning the street into a shattered tangle of asphalt. “Falcon was already a disaster,” said Burns, “so keeping it contained to that one road, should it overflow again, became the focus.” Sandbagging resumed.

It wasn’t the first time Parker Cove had faced a crisis like this one. Almost two years before, the White Rock Lake fire, one of the largest and fiercest the region had seen, burned to the edges of the community, making it one of the many regions in the province facing the whiplash effect of fires followed by floods. That includes many areas in the province burned after the historic wildfires of 2021.

Turns out, the crises are intricately connected. That’s because hot fires burn deep into vegetation and the soil making it more water-resistant. When water comes through rain and melting snow, watersheds can’t hold it all.

Which is why Parker Cove’s flood didn’t come as a shock to geoscientist Jennifer Clarke. After the White Rock Lake fire, she crafted a postmortem report warning the flood risk to Parker Cove was “high” and “unacceptable” for the coming three to five years.

As fires now rage across the country, their frequency and intensity bound to increase due to climate change, experts are urging planners to mind the connective tissue between fires and floods and back again.

Understanding the links between events like those is an important step in a much-needed shift towards preparing for disasters instead of just responding to them, said Kees Lokman, an assistant professor of landscape architecture at the University of British Columbia.

“So that we're not getting stuck in just the emergency world,” said Lokman. “Which is basically where we've been in the past decade.”

‘It was the perfect storm’

Wildfires, particularly severe ones, can transform the way water moves over and through a landscape.

Above ground, a fire is considered most severe when trees are blackened, their needles and leaves are gone, and the forest’s understory is eliminated. In an unburned forest, those trees help moderate the amount of water on and in the ground. Without that plant buffer, sudden spikes in rainfall or snowmelt hit the ground faster.

That effect is magnified by the burn level below, also known as a fire’s “soil burn severity.” When a fire burns hot, it changes the density and mineral composition of the soil below, creating a water-resistant layer on top.

“At a certain level, sand turns to glass,” said UBC adjunct professor Peter Wood, who focuses on forestry and climate change. “It's not quite like that. But it's on that level of creating kind of an impermeable, hard-baked surface.” When that happens, water can’t seep into the soil like it usually does. “When those rains come, they've got a waterslide to go down,” said Wood.

And those flood triggers are escalated further when a wildfire is located on a steep slope, and when the fire burns at high elevations that get lots of snow in the winter. When temperatures rise in the spring, the ample snow on the ground melts fast and heads downhill.

The wildfire in Parker Cove’s watershed — called Whiteman Creek — ticked each of these boxes. Its steep, unstable slopes burned at high elevation, and over half of it burned at high severity. When combined with the spring’s rising temperatures, the water came down fast and with little warning.

“All those factors combined, " said Clarke. “It was the perfect storm.”

Parker Cove residents are working together to divert the flood water away from properties and down the Falcon Ave to Okanagan Lake pic.twitter.com/Y1tmK1UtO3

— Vernon Matters (@VernonMattersca) May 2, 2023

Parker Cove’s flood arrived quickly, but so did support from the Okanagan Indian Band. “I was so impressed,” said Burns, recalling two skilled excavator operators who worked around the clock to save Whiteman Creek Bridge from falling — an event that would have made the flood’s damage substantially worse. A steady stream of sandbags from the band and food from the broader community provided constant support and morale to the community, she said.

Burns said their property manager had been working around the clock. “We’ve all taken care of each other.”

The band also worked before the flood to prepare, said Burns, who said they conducted regular flights over the region to calculate snowpack and monitor the risks. “It was super comforting to hear all of the things that they had done previously,” she said. The Okanagan Indian Band declined The Tyee’s request for comment at this time.

Across the province, responsibility for disasters like these are a mixed bag. The provincial government largely handles damages to Crown land, as well as highways and roads, said Central Okanagan Regional District’s manager of engineering services Travis Kendel. Municipalities and regional districts like Kendel’s, meanwhile, are responsible for many of the decisions surrounding flood management and response in their own jurisdictions. The Parker Cove flood, situated on the Okanagan Indian Band’s reserve land, is under jurisdiction of the band.

The Ministry of Emergency Management and Climate Readiness provided an emailed statement saying it provides funding and other supports to First Nations and municipal governments through programs like the Community Emergency Preparedness Fund, adding “the province has been increasing B.C.’s preparedness and mitigation efforts due to the increasing severity and frequency of disasters caused by climate change.”

Indeed, in an era of climate change, multiple interrelated environmental crises like wildfires and floods mean those governments face growing challenges in the years to come.

Lokman is among a growing chorus of researchers and community activists calling for a more systemic approach to addressing disasters we know are coming, rather than treating them as one-off events.

“There seems to be funding every time there's an emergency,” said Lokman, “but we're not spending a lot of funding to proactively change our landscape so that we don't need to spend that money in the event of an emergency,” he said.

Those proactive changes can run the gamut, Lokman says. It can include actions like widening streams and tributaries to lessen impacts on major water channels; drawing on prescribed, timed burning techniques to lessen the potential for rampant wildfires, and can sometimes include tough land use conversations, including whether to relocate homes and communities away from high-risk areas.

Parker Cove is situated in what’s called an “alluvial fan” — the area at the base of a valley where the slope flattens out. These landscapes are a growing concern for municipalities across the province, said Clarke, and there’s work underway to map out these fans to address the risks they pose.

“That's where we see a lot of the impacts,” she said. “In a mountainous province, they're also the most desirable places to develop. So it’s a challenge.”

Lokman argues that the most important precursor to any preventative actions — whether widening streams or broaching conversations around land use and relocation — needs to begin with community-driven discussions around what matters and what the trade-offs might be. “The best solutions are those that are connected to the shared values of those that will live with the risks,” said Lokman.

A proactive approach that considers the linked effects of climate change can help make the best use of efforts to protect ecosystems, said Lokman. Work in streams to protect salmon, for example, can include efforts to mitigate floods.

Recent months have Lokman feeling hopeful. Last December, B.C. appointed Bowinn Ma as the province’s first minister of emergency management and climate readiness and established a ministry in that name. “It really offers opportunities for integrative thinking,” he said, adding that so far, the province appears amenable to a more proactive and systems-wide approach.

But Lokman remains tentative about the ministry’s impacts so far. “I think it’s a bit early to tell,” he said.

Kendel from the Central Okanagan’s Regional District said the province has “recognized the need to shift towards mitigation and preparedness, in addition to recovery. He hopes to see that shift reflected in the province’s anticipated amendments to the Emergency Program Act.

“We'll see how everything pans out and what it looks like,” he said. “Right now, we're moving in a really good direction.”

Logging towards disasters

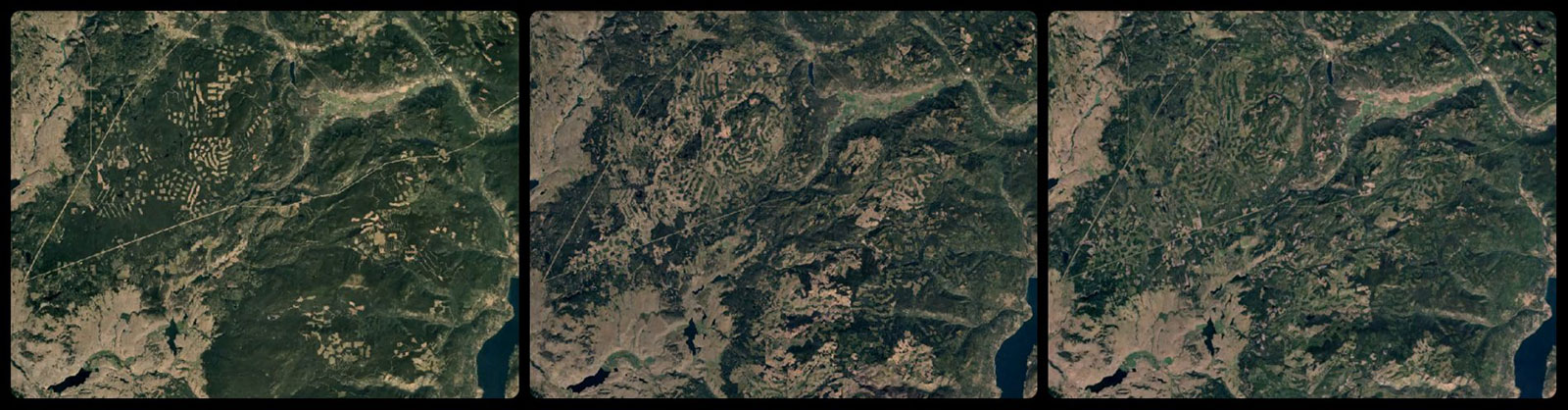

But there’s a key weakness in the province’s approach, said UBC’s Wood, because it tends to ignore the impacts of the forestry sector. Just like wildfires can transform the landscape, so can clear-cut logging.

Areas that have been industrially clear cut lose much of the water-storing capacity mature forests excel at, said Wood. Imagine shaking off a Christmas tree sitting outside that had been freshly rained on, he said: “Just think about all that water that comes out.

“In a context of an entire landscape, it really counts to have a whole lot of trees holding up that water where a significant portion of it never touches the ground.”

Without that plant life and the root systems they rely on, water flows through the landscape faster. That means logging can lead directly to flooding, and it can also contribute to flooding’s intermediary — wildfires.

In fresh clearcuts, logging companies also tend to leave their unused wood — about 40-60 per cent of the biomass — in slash piles that can act as tinder.

Clearcuts also tend to bring fire to areas it wouldn’t necessarily go. Wildfires in mature forests tend to be patchy — avoiding or burning some areas. “It might not burn where it's super wet, close to a stream,” he said. But clearcuts offer an open path for fires to burn hot.

Even as replanted forests start growing back, the risk factor remains. “Younger forests are just very, very fire-prone,” said Wood. Young homogenous plantations tend to have trees with thin bark that burns easily and with branches low to the ground. “Everything about them is vulnerable. Mature forests, on the other hand, are better able to withstand fire and to maintain more of their ecosystem functions afterwards. “It’s much less of a total reset,” said Wood.

A preliminary study found that over 70 per cent of Oregon state’s record-breaking fires in 2020 occurred in areas that had been clear cut, and were in different stages of growing back.

According to Clarke’s postmortem report, there is no publicly available and up-to-date assessment of how extensively the region surrounding the White Rock Lake fire was logged prior to the burn.

Wood said B.C. appears unwilling to draw lines between wildfires and logging, noting B.C.’s latest climate risk assessment made no mention of forest activity as a risk factor for wildfire.

The Ministry of Forests did not respond to a request for comment from The Tyee about whether they consider harvest activity to be a factor exacerbating flooding and wildfires, and whether they take wildfire risk into consideration when planning future logging. Instead, they said reforesting areas that have been burned and damaged by the pine beetle “is essential to building climate change resilience, including flood prevention.”

Tolko Industries Ltd., a major forest operator in the region, declined to comment on the connections between their logging and the White Rock Lake fire.

Wood wants to see the government take fire and flood risk into account when it assesses which cutblocks get the OK to go ahead, and how those cut blocks are logged. “What we need to do to mitigate fires and floods is not rocket science. It's been known for awhile. But it involves lowering the cut,” he said.

Lokman agrees that taking a hard look at forestry is key, as is implementing selective logging techniques to practice forestry while lowering the cut. Adaptation options like this might be less profit-driving for industry in the short term, but a win for communities who will ultimately bear the costs. “The public often has to pay for it, physically and financially as well.”

As she spoke on the phone from Parker Cove, Lisa Burns was still looking out at a backyard full of sandbags, debris and pieces of broken road.

Community members are attuned to the ever-present risks posed by fire and water. They don’t stack firewood next to their houses, and they cut branches of cedar trees up to the top. They have sandbags at the ready. The community is rebuilding, but the recent crisis unearths the not-too-distant past, said Burns. “It brings up a lot of stuff,” she said. “It has been a tough couple of years for everyone.”

But Burns said the community has proven a critical ingredient for those facing recurrent disasters like the one that hit Parker Cove. She takes solace in knowing she and her family are not alone and everyone will pull together.

And if another disaster comes, Burns knows there will be bedrooms for neighbours to stay in and kitchens open for shared meals.

“Both of my children have said, ‘So Mom, are you thinking about living somewhere else?’ And it's like, no. This is where we live. This is where we want to be.” ![]()

Read more: Environment, Urban Planning

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: