Looking at the patient’s health records on his computer screen, the data transfer specialist could see they had received five vaccinations. But it was impossible to know what they had been for.

The records had come that way in a transfer from one of Canada’s biggest providers of electronic medical records. “Essentially, they have stripped out the type of vaccination,” the technician said, speaking on condition of anonymity as he was not authorized by his employer to talk publicly.

A doctor or other health professional looking at the record would have no way to tell if the patient was due for a particular vaccine or if they had already had it. That kind of incomplete information, the technician added, “could cause a significant health issue.”

The problem is typical of how medical files arrive dangerously incomplete or otherwise corrupted, he said. “It’s a daily frustration for everyone, including the doctors.”

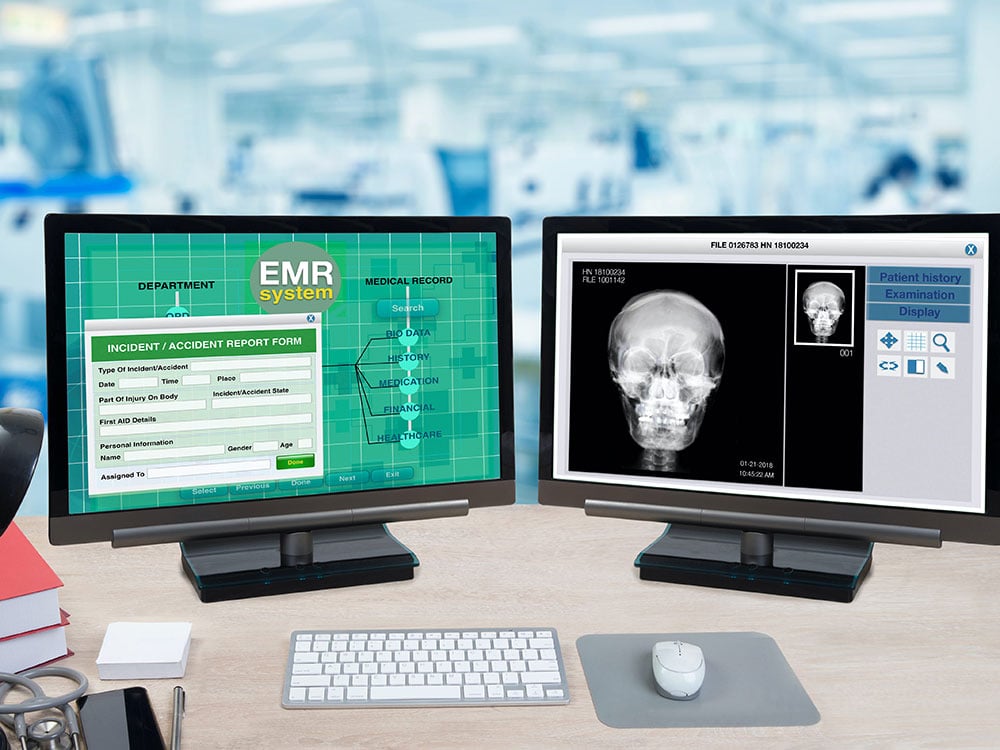

For decades electronic medical records, or EMRs, have held promise as a way to make health care better, safer and more efficient for patients, providers and the system as a whole.

And yet despite hundreds of millions of dollars having been spent, and roughly 93 per cent of doctor’s offices adopting EMRs, there is still no national or provincial system in Canada. Instead there is a sprawling patchwork of dozens of providers and numerous products with no agreed upon data sharing standard that would allow them to work better together.

Patients see the failure. A digital health survey Canada Health Infoway released in April found that a quarter of respondents said their care providers did not have their health information or history ahead of or during their visit.

Nearly one in three said they had “experienced at least one gap in communication and co-ordination of their care in the past 12 months.” The figure was even higher for people with chronic conditions or who had large numbers of encounters with the health system.

As with many issues in health care, mainly delivered by the provinces with some federal government support, how best to fix the problem is a subject of much debate and little agreement. There is no national standard and while some provinces have mandated one, B.C. has not.

“In an ideal state, every patient, every hospital, every provider would have access to all the information they need all the time, and there is not an easy way to do that at this point in time,” said Joshua Greggain, president of the Doctors of BC, in a March interview.

“Without a massive, sweeping, courageous change that will cost billions of dollars, there isn’t an easy path forward to pull all the current information together,” he said.

Even systems run by the different B.C. health authorities and other provincial organizations can’t talk to each other, Greggain said. “There’s not interconnectivity between those entities, so there’s a bunch of siloing of information that doesn’t connect to each other, creating the barriers that we face.”

He gave the example of a cancer clinic in a hospital where the clinic and the health authority that runs the hospital are using different versions of an EMR from a particular vendor. “They don’t connect to each other,” he said, “even though the patient’s in the same physical space in the same physical hospital.”

There are at least 15 EMRs in common use in Canada in physicians’ offices. As of 2021 even the most popular, Accuro EMR, owned by QHR Technologies, was used by no more than about 17 per cent of physicians according to survey results. QHR has been owned since 2016 by grocery store corporation Loblaws Companies Ltd.

The other big providers are telecommunications company Telus Health, which owns and operates at least five different systems, and WELL Health which has at least four. The sector is similarly fragmented in the country’s hospitals.

A Doctors of BC survey of its members in 2022 found 81 per cent of respondents “would prefer to have fewer or a single EMR.” The primary reason they gave was “fewer EMRs would support interoperability and reduce silos and barriers to information sharing.”

More than 10 per cent were considering switching vendors, but concerns about data portability were making doctors reluctant to make changes even when they were unhappy with their current system.

The technician said certain providers are worse than others, and problems transferring data between them are common. Examples included missing data, missing attachments, mislabelled files and incorrect forms being used that resulted in data fields getting populated with nonsense.

One frustrating case was a transfer of files from a very small clinic that generated almost 300,000 records, roughly 500 per patient per day. It was far more than would normally be generated.

After investigating, the technician discovered the high number was the product of a glitch where the transfer duplicated records every time they mentioned a new medicine, date or doctor. When a doctor wrote a prescription on a particular day, instead of one record the transfer created three.

The more complicated the file, the more records it generated. One involving four doctors, three medicines and three dates turned into 36 records. When the technician eventually redid the transfer, there were a much more manageable 12,000 records.

It is typical, he said, for data to arrive late, incorrect, or in a format that’s changed, all of which creates problems for the technician, the health-care provider and ultimately patients.

Robert Brown, a retired doctor in Sidney, B.C., says the reason vendors have little interest in making it easier to transfer records is clear. “They’re investing in data because owning the data is the power,” he said, noting that they are competing for market share.

Doctors are legally responsible for maintaining medical records and have to keep a file for at least 16 years after they’ve stopped making entries to it, but in many cases they do not control them and are dependent on the vendors for access.

It’s common knowledge in the medical world, Brown said, that the companies control access to records and that when a doctor leaves a clinic they don’t get their patients’ data in a usable form. The vendors, competing for market share, appear to have little interest in sharing better and in fact have some incentive to make it difficult for doctors to switch providers, he said.

Doctors of BC president Greggain made a similar observation. “That has been my experience as a physician,” he said. “Because I’m a customer and this is a private entity, they want to have me stay with them, so it becomes very difficult to transfer in between.”

None of the three major EMR providers responded to messages by publication time.

A Doctors of BC survey of members last year found “Physicians want a simple, fulsome sharing of patient information across the province with a few exceptions.”

While about 56 per cent were satisfied with the EMR they were using and 43 per cent were satisfied with their vendor, there was recognition that “Changing EMRs is a time-consuming and expensive process.”

At the same time, members said the current number of options in use “creates fragmented communications” and it was an issue that “EMRs in the community and across hospitals don’t communicate with each other.” People who had worked in Alberta, the U.S. or New Zealand viewed the systems they’d use in those jurisdictions as superior.

The world leader, said Greggain, is Estonia. The small country on the Baltic Sea set out years ago to create one EMR that would be used by everyone in health care and the government paid for it all. Estonia has a population a little over 1.3 million, a bit more than a quarter of the number of people who live in B.C.

The countrywide system in Estonia uses blockchain technology for security and allows patients online access to their own records, which are pulled together from the country’s various health-care providers.

“Functioning very much like a centralized, national database, the e-Health Record actually retrieves data as necessary from various providers, who may be using different systems, and presents it in a standard format via the e-Patient portal,” an Estonia government website says. “A result is a powerful tool for doctors that allows them to access a patient’s records easily from a single electronic file.”

It’s the kind of tool Canadians can only dream of. A 2022 survey for the Commonwealth Fund comparing health care in 10 wealthy countries found Canadian physicians were much less likely than those in other countries to be able to exchange information about patients with doctors outside of their practice, including clinical summaries, laboratory or diagnostic test results and lists of medications.

In B.C. and the rest of Canada, EMRs are yet to live up to their promise, Greggain said. “They’ve definitely given us better quality information, they’ve given us unbelievable quantity of information, it’s the synthesis or integration of that information that’s continued to be a burden.”

When health care moved over from using paper charts, there was the expectation that digital records would save time, be more efficient, be clearer and be searchable, Greggain said. While some of that came true, they have also created a daunting flow of information.

“The speed of information has absolutely exceeded expectations,” Greggain said. “The challenge is that’s then amplified a thousandfold over for the amount of information flowing through any of the EMRs, which creates the difficulty where people, physicians, are constantly interacting with their EMR so that upwards of 30 or 40 per cent of their day is information flow and not necessarily patient care.”

He added, “Medicine used to be called death by a thousand papercuts, and now it’s death by a thousand clicks.”

To fix the issues with interconnectivity, the obvious solution would be to follow Estonia’s lead and mandate one EMR system for everyone, but doing so would present its own challenges, he said.

Mandating one system would take choice away from physicians, many of whom are partial to whatever system they are accustomed to using, Greggain said. Many have chosen systems not just based on how well they work, but on what they cost. “It’s this continual balancing measure between interoperability and affordability, as well as choice versus transferability.”

For 10 years Giovanni Armani had a management role leading data migration for Telus Health, overseeing the transfer of about 10 million patient files a year, a job he left two years ago. He no longer works in health care and does not speak for the company, but shared his own personal observations.

“Data transfer in health care, especially within Canada, is a mess,” he said. “It’s extremely difficult. There are limitations in terms of what data gets moved over, the completeness of the data, or how much of the data moves over, how fast it moves over, what access the doctors have.”

Armani first got involved in the field after discovering how hard it was to gain access to his own record, despite claims from governments and others that patients own the information about them. “In reality that’s not true,” he said. “It was guarded behind all the EMRs and fees and doctors. So in Canada the patients don’t own their charts, even though I would say most people believe their chart belongs to them, because the custodians are the physicians, the primary provider, and they get to basically control access.”

Adding a layer, many doctors lack the technological ability to manage the records effectively, so they need the vendors for that. When a doctor leaves a larger clinic to start their own practice or join another practice, he said, data transfers tend to go smoothly when the separation is on good terms, but less well when there are hurt feelings.

“From what I’ve seen they really have to beg, borrow and plead if it’s not an amicable divorce between the doctors,” Armani said, estimating that happens in 10 to 20 per cent of cases.

At the same time, he said, at least in B.C., there are no regulations or standards to ensure transfers go well and that the physician who is responsible has control over the data. While Alberta and Ontario have interoperability standards, a similar effort in B.C. a few years ago known as the EMR-to-EMR Data Transfer and Conversion standard fell short. “It didn’t go anywhere. There was no adoption or no enforcement of it.”

In the absence of standards set by a government, players in the industry do what makes sense to protect their own interests. “Every vendor will have its own format and what they consider to be part of the core data set, and not part of the core data set, how it should come out, what information should come out,” Armani said.

Data residency rules add another wrinkle, Armani added, limiting Canadian vendors to using older technologies than what would be available in the United States or elsewhere, such as advanced language models that could decipher information like handwritten prescriptions or other records that are hard to standardize.

He said there needs to be a standard made and enforced, and in Canada it makes sense to set it nationally since doctors and patients regularly move across provincial boundaries. Governments need to invest in making records interoperable and vendors need to be at the table as standards are developed, he said.

Canadian EMRs may be a mess, but the rewards of cleaning it up will be huge, Armani said. “Ultimately it’s just empowering both patients and decision-makers,” he said. “If we can unlock it, I think there’s benefits for so many things, research and funding and just distribution of physicians. There’s so much power in examining the data that exists in these EMRs, but right now as a country, or a province, or a region, we can’t do anything on that because they are so segmented.”

B.C.’s Health Minister Adrian Dix said the need for better data management is obvious.

He pointed to pharmanet as a recent example of the power of good data management. The provincial drug plan’s centralized record-keeping made it possible to see that a large number of prescriptions for the diabetes drug Ozempic, popular as a weight-loss aid, were going to people in the U.S. and that a surprising number of the prescriptions were being written by one practitioner in Nova Scotia.

The pattern could be seen thanks to the centralized database, he said. “You do that and it really helps you.”

But he acknowledged most of the province’s health data is managed poorly. “You’re right, all of this for the system, this sort of highly balkanized IT systems at the acute level, the different systems, Cerner and Meditech, different health authorities, all of that is a challenge.”

To illustrate, he gave the example of attachment to primary care. The only way the government knows that roughly a million British Columbians — one person out of five — lacks a family doctor is through surveys, he said.

While he has the sense that the situation is improving, the only information available is anecdotal and the government has no easy way to determine if there really has been progress. And if there has indeed been progress, he added, there’s no way to demonstrate it. A better EMR system would make it possible to answer those kinds of questions.

The province’s recent agreement with doctors on primary care includes efforts to fix the EMR problems, Dix said, noting the solution will take more than just setting a standard to be followed. “You can establish standards, but you also have to upgrade the technology.”

The problems are long standing and were mismanaged by previous governments, Dix said. “There’s all these elements of IT in the system that haven’t worked very well and we’re building them out to make them better, but this is the system we inherited,” he said, blaming the problems on the BC Liberal government the NDP took over from in 2017.

“The previous, I think they call themselves a ‘business-oriented government’ catastrophically failed in delivering this, even though money was provided to them under Infoway,” he said. Canada Health Infoway is a federally funded effort to improve information-sharing.

It was so bad that B.C. had its own homegrown eHealth scandal with criminal charges laid against former Health Ministry assistant deputy minister Ron Danderfer and two other people, Dix said. Danderfer pleaded guilty and was sentenced to two years’ probation.

“The mismanagement of this issue at its core, at a time when hundreds of millions of dollars were being provided to British Columbia, was very challenging.”

The federal government’s priority was getting the money out the door and B.C., like other provinces, flailed around with it and failed to build the kind of system that was needed, Dix said.

At the time Kevin Falcon, now the leader of the BC United official Opposition, was the health minister. Looking back, he agrees little was achieved with the money spent.

“I was there when the federal government was pouring all this money into their medical records program and it’s gone on for, it’s still going on presumably, and I think there’s been very little to show for literally hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars,” Falcon said.

“The landscape of government is littered with technology efforts that have been a failure,” he said. “We suffered them when we were in government. The current government I’m sure is having their fair share.”

The health data project was led by the federal government, Falcon added, which has tended to have even worse disasters on technology projects than the provinces.

Nobody from Health Canada was available for an interview. A spokesperson providing a response to emailed questions failed to address why, despite the large past investments in digital health records, Canada lacks a better system.

Over the past year the federal, provincial and territorial governments have developed a draft Pan-Canadian Health Data Strategy that is “reflected in the commitments related to health data” included in recent agreements to improve health care, the spokesperson said.

“The Government of Canada intends to work collaboratively with provinces and territories on four shared health priorities, including modernizing the health-care system with standardized health data and digital tools.”

A modern data system will help save lives, the spokesperson said, adding the work is underway. “This will help ensure Canadians and their health-care providers have secure access to the information they need for quality, person-centred care, and that insights from appropriately anonymized health data are available to inform research and decision-making.”

In a 2019 article in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, Nav Persaud, who teaches and practises family medicine in Toronto, argued for rebuilding the country’s health records system from the ground up, starting with primary care records.

“Despite billion-dollar efforts to promote information transfers between jurisdictions, sharing health information today often requires feeding it through a fax machine or sealing it in an envelope for mailing,” he wrote.

“Care is frequently based on incomplete information: patients try to remember which vaccines they have received, radiography is repeated because the results are not available, and family doctors attempt to piece together what happened during hospital admissions and emergency department visits.”

While it was good that most primary care providers were using electronic health records, there was unfortunately no co-ordination in selecting them. “Some clinicians have even created their own electronic health record,” he said. “As a result, doctors now log into a myriad of separate systems for primary care and hospital records, laboratory and imaging results, and prescription documentation — systems that usually cannot connect with one another.”

He argued for adopting a single electronic health record system, preferably one that’s open source that can be customized to meet local needs. Canada Health Infoway should be given the mandate to pick and improve one system, with input from patients and clinicians, he said, and the provinces and territories should only fund the one option.

In B.C., nearly 20 years ago, the provincial government committed to accelerating the development of electronic health records and making them meet national standards and be compatible with other systems across Canada.

The advantages would be obvious, B.C.’s auditor general wrote in a 2010 report. “Health records in electronic form are not only more legible and more easily retrieved than paper-based health records are, but they provide patients and their health-care providers with complete and up-to-date details about the individual’s health profile,” it said.

Potential benefits included a decreased risk of a patient being sent for duplicate tests, prescribed inappropriate medication or experiencing delay in receiving service. “Overall, by enabling better health-care planning, monitoring of health outcomes and health research support, an EHR offers citizens longer-term benefits such as safer and more effective health services.”

The Health Ministry was moving in the right direction, but “there is still a long way to go before British Columbians fully realize the benefits of having an electronic health record,” the auditor general reported 13 years ago. “Once the components are built, it will still take some time before they are integrated across the health sector and regularly used by health professionals in treating their patients.”

More than a decade later, the path remains foggy.

“There is no North Star at this point,” Greggain from Doctors of BC said. “What we really want to be able to do is serve patients, give patients as much information as available to them, have seamless flow of information between current providers, hospitals, health authorities, etc., ideally across the region, if not the province, if not the country, and we’re a long way from that.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: