When the paneer sold out, that was it for the day.

Since the early 1970s, Indian restaurants and sweet shops were the places to get the fresh cheese. The hub to pick it up was the southern stretch of Main Street in Vancouver, known as the city’s Punjabi Market and Little India, a destination for members of South Asian diasporas from across B.C.

Sweet makers in the Lower Mainland were masters of working with milk, turning it into traditional dairy products. It’s the main ingredient in a number of intricate South Asian confectionary, called mithai in a number of languages, that require hours of attention and are sold from glass cases like jewelry.

Step into a sweet shop in the Punjabi Market and you’ll find gulab jamun, balls of deep-fried milk dough in a cardamom syrup, and varieties of burfi, squares of fudge-like condensed milk, from carrot to pistachio, glittering with edible silver.

It was the sweet makers who made paneer for restaurant dishes and a limited quantity for customers who missed cooking with it from home.

In India, paneer is typically made from buffalo milk. In B.C., sweet makers made it work with cow’s milk, one litre of which could yield 130 to 150 grams of paneer. Jugs of milk would be poured into their woks — the largest standard size could hold 40 litres — to be boiled, then curdled, drained, pressed, cut, cooled in water and sold in small batches.

The quality, though, was “hit or miss,” recalls Gurpreet Arneja, who moved to the city in 1978.

The search for paneer led some locals to make trips across the U.S. border, where a dairy was making it in Blaine, Washington. Arneja’s wife Raj, who grew up in New Westminster, remembers drives to fill up on cheap American gas and pick up a block of paneer.

Unfortunately, the quality there was a miss. “I felt it was a bit rubbery. It broke very quickly,” Raj recalls. Like many, she opted for making it at home, but only for special occasions because it’s a lengthy overnight process.

Paneer is a fresh, acid-set cheese — a category that includes the German quark and the Latin American queso bianco — which doesn’t require aging and can be made with an accessible acid like lemon juice. One of Raj’s go-to dishes is matar paneer, paneer with green peas in a tomato sauce.

In the 1990s, more restaurants and sweet shops opened up to serve the growing number of Indian immigrants settling in suburbs like Surrey.

India is a dairy titan of a country, producing and consuming the most milk in the world. In the north, paneer is a common source of protein, especially for vegetarians. But despite the local demand for this protein brought about by newcomers, there weren’t enough paneer-making sweet masters to go around.

One day, Arneja was having lunch with his niece’s husband Vineet Taneja, who had arrived from New Delhi in 1993. Their conversation landed on the paneer problem.

Neither of them worked in the food industry. Arneja was an instructor of industry and technology at Kwantlen University College. Taneja was a manager of a Future Shop.

But Taneja’s father and brother were engineers who manufactured dairy equipment in India. He wondered if they could produce Indian dairy products in Canada on a commercial scale.

Could paneer be packaged and sold out of fridges? Could the shelf life be extended beyond a matter of days? Could they make enough that a block could be sold for a few dollars? Beyond paneer, could they make an entire repertoire of Indian dairy products?

If the two were to embark on such a venture, they knew they would be treading new territory even by India’s standards because the country doesn’t have a strong cold supply chain. A product like paneer was something that people were used to buying fresh from a local maker. “It was all being made in an artisan fashion all over the country,” said Arneja.

Starting a new business in dairy processing would also mean stepping into Canada’s highly regulated dairy industry, with its strict regime of quotas. Critics have called it a “dairy cartel” while some rival American producers wish they had a system of supply management like it.

Recognizing the scarcity and hunger for Indian dairy, Arneja and Taneja took a trip to Haryana, India to learn about the traditional craft and bring it back.

In 1997, they launched Nanak Foods in growing Surrey. From their start in a 1,500-square-foot facility, they would transform the landscape of Indian dairy in the region — and stock products like precious paneer in fridges around the world.

Securing the shelf

It wasn’t hard to find machinery for making other cheeses that would work for paneer, but it did take a year of experimentation, sleepless nights and wasted milk to get a product they were happy with.

Then came the next challenge: securing shelf space as the new product of a new brand.

“You can have the best product, but if you don’t have the shelf space to showcase it to consumers, it’s not easy,” said Arneja.

At the time, the South Asian grocery chain Fruiticana was just taking off, thanks to the immigration and suburbanization that seeded the potential for new stores in Surrey. Fruiticana’s founder Tony Singh saw the potential of paneer right away and was the first to display it prominently in his stores.

“I remember them coming into my store and bringing in the product from the back of their car,” said Singh. “It was a lifesaver for my wife and my mom. They were making it at home, but very rarely because it’s a long process. From there on, it became a daily, weekly food.”

All the better that Nanak, like Fruiticana, was also based in Surrey. Getting stock directly from a local producer, bypassing the hands of distributors, is important for grocers, especially for a refrigerated product like dairy. There were one or two American companies that had tried to export frozen paneer to Canada, but shoppers didn’t take to it.

Once Nanak’s hit the shelves, the success of the product was in customers’ hands.

Arneja knew it would be a challenge to change the routines and buying habits of people who were used to making the trip to their local sweet shop to buy their paneer.

“People had to be convinced that it’s going to be equally good or better than what they’re used to buying,” he said.

The packaged paneer also had to win the confidence of people who were used to making it at home. Seeing immigrants settle in Canada, he knew that many on tight budgets would not spend money on food they could make themselves.

But the convenience would prove too hard to resist. A block of paneer was about the same price as a jug of milk, which would lose more than 85 per cent of its volume when boiled down to make the cheese. Nanak’s paneer could also be kept in the fridge for up to four months, cutting down the need for commutes to Punjabi Market and local sweet shops to pick up paneer that had to be cooked within a matter of days.

A new market for milk

For Arneja and Taneja, paneer was just the beginning. While they always had other Indian dairy products in mind, there was also a practical reason for expanding their line.

“We realized you can’t really survive producing one food product,” said Arneja. “The stock rotation becomes very slow and expiry dates start creeping up.”

An assortment of products would mean more sales in stores and fresher stock delivered more frequently. Scaling up would also allow them to keep prices low.

But to make more Indian dairy products, they needed more milk.

“It’s very tricky to convince the powers that be to get more,” said Arneja.

While provinces decide how much milk farmers have to produce, the federal government decides how much can be processed into other dairy products.

One of the factors that the Canadian Dairy Commission considers is whether a milk processor will be producing products that might displace an existing one. Nanak sparked no worries of this, instead identifying new products for a new market that would potentially create more demand for milk.

The duo made the case that it would be a “win-win” situation for Nanak as well as B.C. farmers.

Together with the BC Milk Marketing Board, they were able to convince the Canadian Dairy Commission to give Nanak higher quotas every time they came up with a new product.

Indian dairy products have a long history in B.C., says Satwinder Bains, the director of the South Asian Studies Institute at the University of the Fraser Valley.

One of them is ghee, the clarified butter foundational to South Asian cuisines and religions and has medicinal properties.

Immigrants were making it as early as 1908, when Vancouver’s first gurdwara opened in Kitsilano, she said. Ghee was used in lamps and in the karah parshad, a sacramental food offered to all visitors.

Bains has also heard stories dating back to the 1940s of Indian families in B.C. keeping milk cows, which they likely made into traditional dairy products because nothing was available in stores.

Bains happened to be sitting on the BC Council of Marketing Boards, which oversaw the milk board, when Nanak was first requesting milk quotas. The milk board came to them asking, “What is paneer? What is this thing?” Bains, a rare South Asian voice on the board, was there to explain it to them.

From there, Bains watched Nanak take off, filling a demand that had been around for decades using the province’s own milk.

“It was a game changer,” she said. “We’re not getting milk flown in from Quebec. It’s right here in our backyard, our neck of the woods.”

Filling the fridge

With local sweet makers in limited supply, Nanak stocked sweet shops with Indian cheeses and other dairy products to help out.

“We cut their production times drastically,” said Arneja. “Instead of a sweet maker spending time to make an ingredient, they would purchase the ingredient from us and concentrate on making the finished product.”

One of the items Nanak supplied was chhena, disc-like patties made from kneaded curds. The popular dessert rasmalai consists of chhena served in a clotted cream called malai, flavoured with saffron and cardamom, and a sprinkling of nuts.

And for people who wanted to make sweets at home, Nanak produced packs of khoa for sale in stores, the milk solids that serve as the base of many treats.

After paneer, Nanak tackled ghee, which people were used to making at home by cooking down store-bought butter.

There were occasionally jars sold in local stores in small quantities. Dairy products are incredibly difficult to import in Canada and it’s likely that they were brought over in luggage and resold illegally.

Then came dahi, Indian-style yogurt. While it was commonly made at home, it could come out inconsistent.

“It’s very hard to control the time and temperature of the incubation,” said Arneja. “When it’s produced at a commercial level, everything from the time, the temperature, to the addition of the bacterial culture is controlled right down to a science.”

With Nanak producing these hard-to-make staples that didn’t used to exist in stores, the brand became a household name.

“When we bring on new product, people are still hesitant because they think they can make it at home,” said Raj, who joined the company as the director of corporate engagement and philanthropy. For years before her husband started Nanak, she too avoided the store-bought paneer from the U.S. because she could make it herself.

“[But] because people are finding it so handy, and because the taste is so authentic, things are flying off the shelves all the time.”

From handmade to high tech

Canada’s dairy regulations that were tough to navigate in the beginning proved to have an upside: building international trust in Canadian dairy due to the strict standards.

Nanak began shipping internationally as early as the year 2000. Business has only taken off from there.

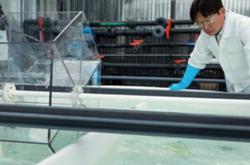

Inside Nanak’s over-100,000-square-foot production facility in Surrey, items are wrapped by thermoforming, laser coders are used for inkless printing and x-rays inspect products for anomalies.

Over the years, Nanak went on to develop their own sweets in refrigerated and frozen packages: rasmalai, gulab jamun and burfi among them. In 2011, when the duo brought their rasmalai to Germany to show off at Anuga, the world’s largest trade fair for food and beverages, it took the prize for top innovative product.

The company entered another market, one that had been dominated by western offerings like Hamburger Helper for so long: ready-made frozen foods. For those needing a quick bite for themselves or to serve guests — but wanting Indian flavours — Nanak produced its line of products that included pakoras, poppers and pizzas.

From there, paneer took to the skies. Nanak supplied it to producers of in-flight meals, along with their appetizers and desserts.

More products meant more milk, but also more technology. But in India, artisan dairy products and sweets were not made on this scale.

“There was no standardized or readily available equipment,” said Arneja.

Food processing technologies from multiple countries and companies had to be brought together. For kaju katli, a sweet made from cashew paste served in diamond-shaped slices, Nanak brought in equipment from Japan, Germany and the U.S. in addition to Canada to create a single production line.

But even this large facility isn’t big enough for the company’s needs. When the pandemic came, it stretched what space the company had because they had to hang onto product that they could not ship.

Nanak is currently waiting for the City of Surrey to approve their proposal for a new facility in Campbell Heights, to amalgamate their production and storage. For their round-the-clock workers, they’re also proposing a 20,000-square-foot daycare. The size of the entire facility: 293,000 square feet.

Paneer planet

Products like paneer were hard to introduce to western shoppers and supermarkets for many years.

“Getting shelf space for a product that was not ‘mainstream’ was not easy,” Arneja said, imagining non-Indian shoppers walking into a store, picking up the paneer, and going, “How do you pronounce the thing? What is it? How do you use it?”

It wasn’t until a little over a decade ago that he noticed more interest in their products from western consumers. As they frequented Indian restaurants, they became curious about buying Indian products and eating them at home. Now, Nanak’s products have broken into certain locations of big grocers like Loblaws, Save-on-Foods, Walmart and Costco.

Nanak’s exports have followed the Indian diaspora around the world. There are stores that stock their products in over 20 countries, such as Germany, Hong Kong, Japan, Singapore, Australia, Trinidad and the U.A.E. For the international market, Nanak developed a special frozen version of paneer with a shelf life of 14 months to be thawed when used.

In Canada, the Indian diaspora continues to grow. India has become the top country of origin for immigrants as well as international students.

“They’ve made it much easier for everybody,” said Fruiticana’s Singh, who now has 22 stores in B.C. and Alberta and knows that just about everyone is picking up a jar of ghee.

“They’ve done a great job in bringing in a taste of India that was hard to find and hard to make at home. Rasmalai was my favourite dessert. It was only made at my house once a year. Now, I can open the fridge and it is there for me twice a day.”

Nanak is now there in the kitchens of those finding their footing in a new home, whether it’s young students just learning how to cook, tech workers logging long hours or family members making dinner for everyone under the roof. The ingredients are there for celebrations, but also everyday meals, saving them time and bringing comfort and connection.

“Gulab jamun, rasmalai, some of the halvas, paneer — all of these items are not easy to make,” said Arneja. “It’s changed their lifestyle. It makes them feel at home. Leaving home in India, going to a different land, they [don’t] have to miss out on basic staple foods.”

Read more: Food, Labour + Industry

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion and be patient with moderators. Comments are reviewed regularly but not in real time.

Do:

Do not: