For the first time in a decade, Johnny stared at a concrete wall with a paint can in his hand.

He was nervous.

As a high school and college student in the mid-’90s, he was a graffiti legend in his hometown of Columbus, Ohio. Known by his graffiti name Johnny Cashola, Johnny used graffiti as a way to meet new people and express his creativity. He asked that we withhold his last name in this story to protect his privacy.

Johnny always doodled as a kid, and as he got older, he painted trains and alleyways throughout the city with his own tag.

He dreamed of becoming famous on the streets.

Over the years, graffiti gets painted over or removed. However, his work in Columbus is still untouched. “You can’t talk about Columbus graffiti history without mentioning my name,” Johnny said. “The newer generation are like, ‘He’s from the ’90s, you don’t mess with him.’”

After he met his wife and started a family, Johnny stopped doing graffiti. Yet as his son got older and began spending more time in school with his friends, Johnny began looking to see how he could meet new people himself.

After he moved to Vancouver for work last summer, he stumbled upon the Vancouver Coalition of Graffiti Writers, a now-defunct Facebook group that brought together graffiti artists and admirers in Vancouver, and connected with a group of people who offered to take him out painting.

On a hot day last summer, Johnny ventured out with a new friend to paint at a popular graffiti wall at Leeside Skatepark in East Vancouver.

He was nervous. Even though Johnny had rediscovered his old passion, he had seen other people who had retired, come back into the game, and flopped. He’d hear about current graffiti artists chastising older artists who lost a step. For guidance, he even asked his new friend if they outlined or made their 3D designs first.

After a couple of hours, Johnny took a step back from his artwork and his doubts faded away.

“Ahh,” he thought to himself. “I think this is going to turn out alright.”

The blue arrows and shapes were painted to his liking, and the 3D fades accentuated the letters in his design.

A new municipal government, a new graffiti prevention plan

Two years after it was established in 2020 to connect graffiti artists and fans, the Vancouver Coalition of Graffiti Writers shut down last month.

Leading up to the municipal election last month, A Better City Vancouver, more commonly known as ABC Vancouver, promised a graffiti prevention plan targeted at preventing illegal graffiti painting on the city’s streets.

The plan outlined building a specific Vancouver Police Department unit aimed at identifying and removing graffiti materials from repeat offenders. It also pledged to build legal graffiti zones in Vancouver.

Following ABC’s landslide victory, which saw mayoral candidate Ken Sim defeat incumbent Kennedy Stewart and the party claiming seven of the 10 seats on council, the page’s organizer, Trey Helten, closed the Vancouver Coalition of Graffiti Writers' Facebook page.

Helten said the decision to shut down was made to protect artists and to address the uncertainty of how the new municipal government would handle graffiti on Vancouver’s streets.

“Campaigns make promises. ‘Today we’re going to do all this stuff,’” Helten said, but he noted politicians don’t always act on their promises. On local campaign promises like ABC Vancouver’s pledge to prevent the spread of graffiti in Vancouver, Helten said, “It’s a strategy for someone to say ‘I’m going to get rid of graffiti’ and boom, you get all these votes.”

ABC Vancouver Coun. Sarah Kirby-Yung was disappointed when she heard that the Facebook page closed down. She’s a fan of city art and cites the Shoreditch neighbourhood in London as her favourite spot to see street art. Shoreditch is a hip community that has organized graffiti tours and attracted international artists to design murals.

“It has this really great vibe,” Kirby-Yung said. “People walk around the corner and you never know what you’re gonna expect.”

But she says Vancouver doesn’t have the same culture as Shoreditch, yet. Murals have been defaced and businesses have been tagged without their consent. Kirby-Yung says the city wants to strike a balance between creating spots and neighbourhoods for artists to paint and making sure people don’t feel like they are targets of vandalism.

“I’m a huge proponent of public art,” she said. “I think we have a huge opportunity to financially figure out how to help art thrive in the city.”

‘What this whole community wanted’

At its highest point, the Coalition of Graffiti Writers page had around 1,900 members.

Helten, who is also general manager of the Overdose Prevention Society, formed the group with his OPS colleague Sarah Blyth. As the toxic drug crisis continued to unfold in Vancouver, Helten and Blyth wanted to make the dark and dreary alleyways around the OPS more colourful.

In August 2019, the duo created an alley mural project to use public art like graffiti to spruce up the alleyways and commemorate those who had lost their lives due to overdose.

“Vancouver’s always had a graffiti culture, but that alley was sporadic, the colour splashes were really grey,” Helten said. “I remember this day, we walked outside, and [Blyth] was like, ‘this place is really grey. It looks terrible and this is a horrible place to die in.’”

A few months later, Helten connected with James Hardy, otherwise known as Smokey Devil, to launch the page.

The goal was to have a forum for graffiti artists and admirers in the city who wanted to praise artwork.

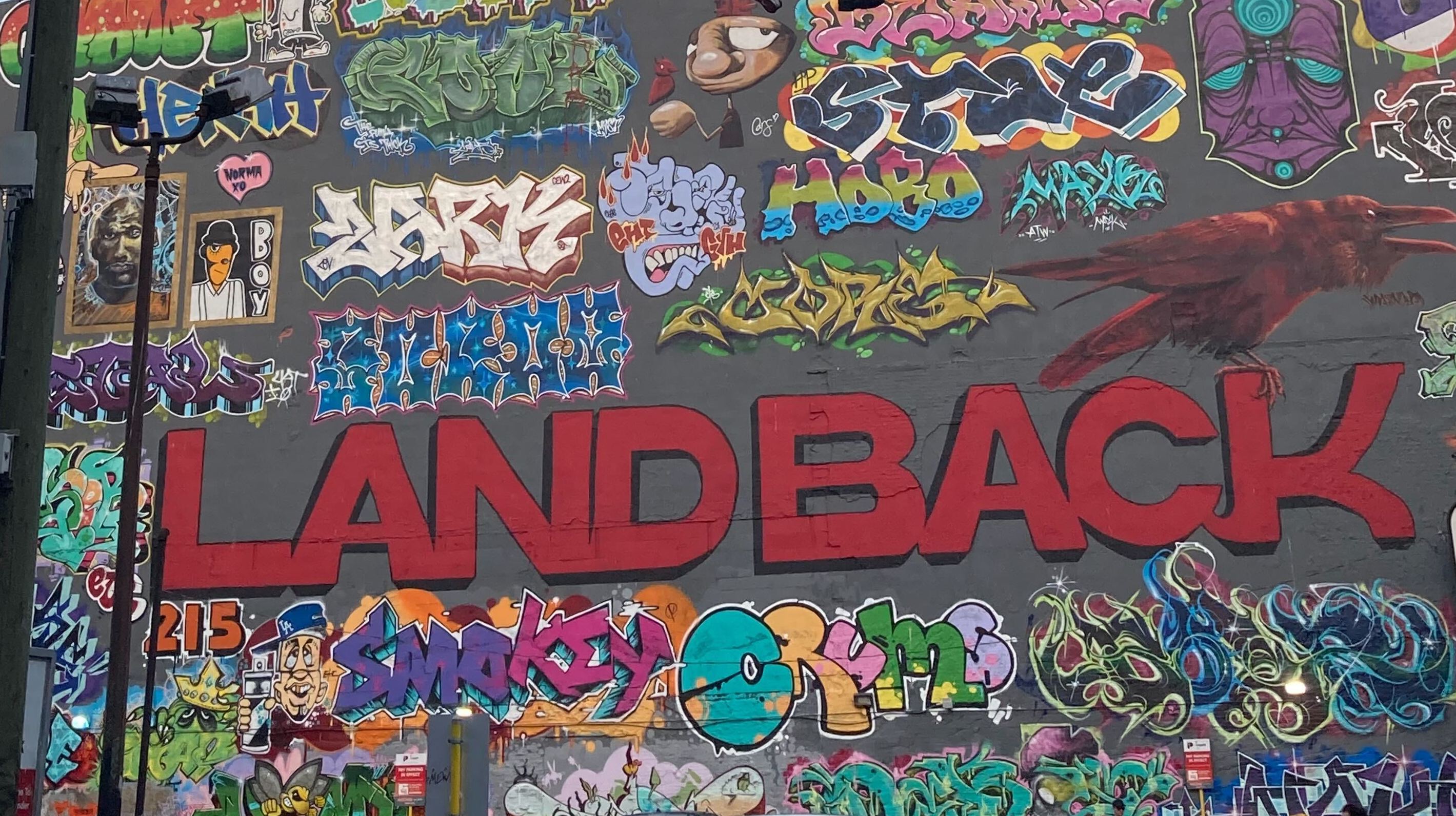

The group also connected artists with each other and businesses who wanted graffiti-inspired artwork, and provided a point of community consultation for collaborative projects including a six-storey “LAND BACK” graffiti mural at 99 W. Pender St. in 2021.

When Helten secured space to paint the mural, he asked members of a DTES news and updates Facebook page what they wanted to see written on the mural. An overwhelming majority of people wanted it to be Indigenous-focused, and Helten got 37 artists to contribute to the project.

“The Land Back wall is one of the most memorable things that happened,” Helten said. “It felt good to include people, and it felt important that it’s not just graffiti artists, it was what this whole community wanted.”

Not all graffiti is vandalism

Amid all the colour that graffiti has brought to the city’s streets, there was a 70 per cent spike in reports of what’s known as “nuisance graffiti” during the pandemic. Unlike graffiti displayed on legal walls, nuisance graffiti are tags and designs that are painted on businesses or private property without their permission.

Helten said that spike could be related to all the boarding that went up during the early days of the pandemic.

“To a street artist, that’s just canvas,” Helten said.

Over the past year, vandalism and illegal graffiti have continued to be a point of frustration for community members and business owners in Vancouver’s Chinatown.

A mural on East Georgia Street that highlighted the diversity of Chinatown was the subject of graffiti tagging in April. In May, a mural on the walls of Ten Ren Tea & Ginseng Co. by Carolyn Wong that celebrated the neighbourbood’s culture was defaced weeks after its creation.

That same month, Tommy Wong, owner of Chung Shan Trading Co. in Chinatown, wrote a message on his own storefront that denounced the people who have repeatedly tagged his business with derogatory and racist messages.

Businesses can be fined up to $500 for not removing graffiti on their walls within 10 days of being served a notice from the city. Helten thinks that the city should get rid of the removal fee.

He also believes the removal timeline is the main reason why businesses have issues with graffiti.

If that law was changed, he said, there wouldn’t be as much anger towards graffiti. He added that the city should set up a program that facilitates collaboration between street artists and businesses.

“There’s an opportunity to create more jobs for street artists,” Helten said.

A council motion passed last week includes plans to support Chinatown. One of the action plans calls on city staff to look into the possibility of removing or waiving fines to property owners who are victims of graffiti.

Kirby-Yung expects feedback on the bylaw by the first quarter of 2023.

“It was a concern that was raised by some folks. They said they get fined a few times and are like, 'Ok, come on. It’s costing me all this money to clean this up and then you want to charge me if I don’t don’t remove it quickly enough?'

“I felt like it was rubbing salt in a wound for people.”

In June, to reconcile with the businesses that were impacted, Helten and Smokey collaborated to paint murals in Chinatown that call on Vancouver’s graffiti artists to respect the neighbourhood.

Helten and Smokey hoped the art would show that not all graffiti is vandalism.

“Me and Smokey went over there, did outreach, to say, ‘Hey, not all of us are like this. We don’t destroy other people’s artwork.’”

Andrea Curtis, executive director of the Vancouver Mural Festival, credits Helten, Smokey and Blyth for taking initiatives to organize and advocate on behalf of graffiti artists in the city.

“I firmly believe that Trey deserves an award for outstanding Vancouverite,” Curtis said.

“He’s taken my team on tours through back alleys, Chinatown, and he’s not just showing us the different lettering, tags, introducing us to Smokey D. At the same time, he would walk by and gently nudge someone who might be slumped over on a door frame, making sure they’re alive.”

Johnny Cashola says it’s tough for artists to improve when they’re just starting out. Artists often begin by working on their own tag, using a simple marker on a wall. From there, an artist can expand their work by writing bubble letters before developing a full art piece.

He wishes there were more legal walls set up around the city for artists to refine their craft.

Can graffiti and the city coexist?

Skateboarding, which has been closely linked with graffiti and street art, was once regarded as a nefarious activity in Vancouver’s streets.

In the 1990s, Blyth co-founded the Vancouver Skateboard Coalition — a group that advocates for higher quality skate parks and acceptance of skateboarding culture.

Although skateboarding was highly stigmatized in the '90s, the coalition helped create numerous skate parks in the city and legalized skateboarding in Vancouver in 2003.

Blyth says that to get graffiti to a similar point, graffiti leaders need to continue being organized in discussions with the city. She’s spoken with Vancouver Coun. Brian Montague, who was also a former Vancouver police officer, and is encouraged by his interest in serving artists and the city.

“I felt like they really enjoyed Trey’s art and understood what the collective was doing, and wanted to have more conversation about how we could all work together,” Blyth said.

Curtis adds that it will be important to include graffiti artists and local business owners in all conversations regarding the future of graffiti planning.

“The business owners that have been suffering from [tagging], they’re looking to Vancouver’s first Chinese-Canadian mayor to stand up for that,” Curtis said. “Ken Sim and the ABC party have their work cut out for them in navigating a city that is for everyone and finds a way to celebrate the artists.”

Curtis doesn’t think extra policing will be a meaningful solution to illegal graffiti in Vancouver. She thinks sanctioning certain alleyways for graffiti as part of a pilot project could be one way to properly facilitate graffiti in the city.

In 2021, Vancouver council designated a 55-metre-long back alleyway at 133 W. Pender St. to become the city’s first legal graffiti wall. The project was the brainchild of Helten and the Vancouver Coalition of Graffiti Writers. Over $1,200 was raised through a GoFundMe to help set up the wall and collect supplies.

Paola Qualizza, chair of the Vancouver Public Space Network, said in an email interview with The Tyee that Vancouver's engineering department — which manages the pilot — will report back to council sometime in 2023 after it’s been in place for one year.

Qualizza hopes that the space will be kept and that street art will be expanded in the city.

“We also hope that there might be ways to enable more areas and likely through different models, ideally without needing the city to manage this,” Qualizza said.

“This could mean a role for local business associations, businesses, non-profits or neighbourhood groups — groups that have blank walls or streetscapes that could benefit from some colour and a bit of collaborative placemaking.”

‘The heartbeat of graffiti is illegal’

To establish a more cohesive graffiti culture in Vancouver, Kirby-Yung wants to build a community between artists and property owners. She understands that tagging can be seen as a form of creative expression for artists, but advises people to get in contact with businesses before painting on their walls.

Following the creation of the legal graffiti wall, the city has looked at other ways of fostering graffiti on Vancouver’s streets.

In the summer, city councillors Lisa Dominato from ABC Vancouver and Pete Fry from the Green Party brought a motion forward that suggested the city look at permitting “free-for-all” graffiti laneways in Vancouver. Kenneth Chan of DailyHive reported that the city council looked at Graffiti Alley in Toronto and the Venice Art Walls in Los Angeles as two examples of what other cities have done to manage and promote graffiti.

Kirby-Yung is open to expanding the pilot and is looking forward to hearing feedback from the legal graffiti wall at 133 W. Pender St.

“I am interested in having an artful city and I’m really interested in having conversations with people about how we do that.”

In the meantime, even though the Vancouver Coalition of Graffiti Writers has closed shop, artists like Helten and Johnny are still out on the streets, active in their craft. At the end of the day, campaigns make promises, Helten said, and it’s too early to tell whether ABC will act on their pledges.

“The heartbeat of graffiti is illegal, it’s an illegal act, [but] it’s freedom of speech,” Helten said. “And you talk to most of these graffiti artists, a lot of these prolific ones, they say street art, painting, graffiti, has kept me out of more serious problems.”

Johnny Cashola still has aspirations to paint. He hopes to stay connected with Trey and the artists he met through the group.

“It gave me community, but it also gave me reassurance of where I can and can’t go,” Johnny said. “One of the first things I said was, ‘Where can someone paint without getting in trouble here?’” ![]()

Read more: Art, Municipal Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: