Toxic drugs killed at least 161 people in British Columbia in April, the sixth anniversary of the province’s declaration of a public health emergency over drug poisonings.

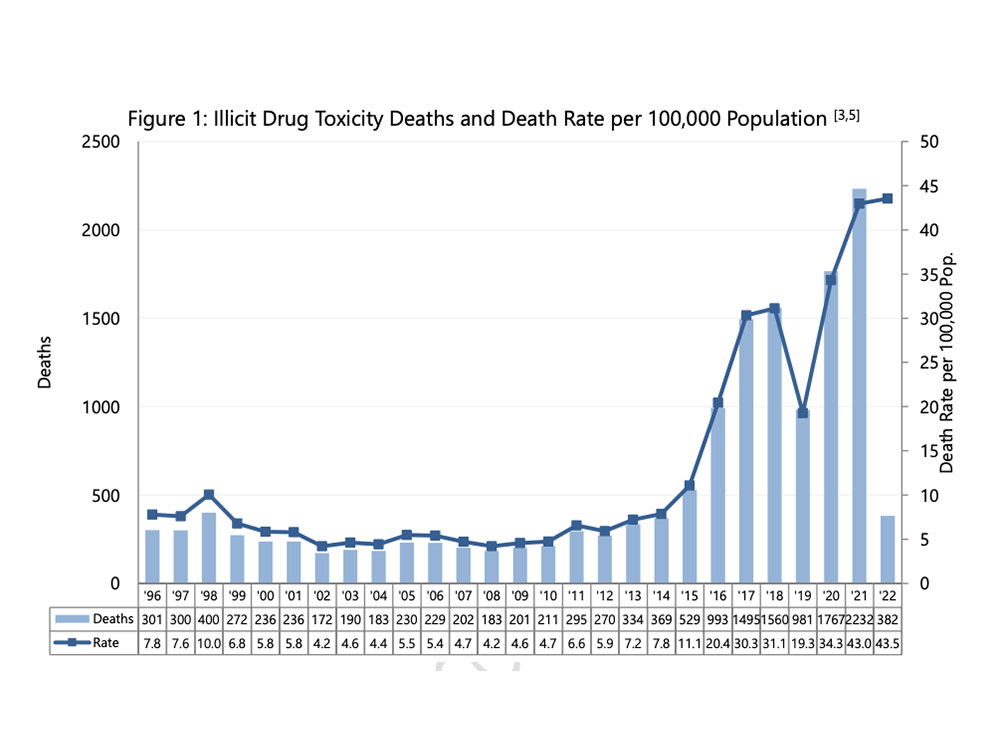

Data from the BC Coroners Service shows deaths in 2022 are on pace to match 2021, the deadliest year on record, when 2,236 people lost their lives.

Last year 721 people died in the first four months, compared to 722 deaths in 2022.

That means five or six people are dying on average each day as the drug supply becomes increasingly unpredictable and prescribed alternatives remain difficult to access.

Twice as many people per capita are dying in 2022 as they were in 2016 when the crisis was declared. About 41.1 people per 100,000 are dying right now, compared to 20.4 six years ago.

“Anyone using illicit substances, whether they are regular or occasional drug users and whether they know their dealer or not, is currently at risk from the unpredictable, unregulated supply,” chief coroner Lisa Lapointe said in a news release today.

Drug surveillance data released today demonstrates just how toxic the supply, driven by profit and organized crime, has become.

Fentanyl has been found in about 83 per cent of deaths in 2022, with extreme fentanyl concentrations in up to 17 per cent of deaths in April. Before the pandemic, that figure was about eight per cent.

And benzodiazepines, a class of non-opioid sedatives, are now found in about 45 per cent of deaths, up from 15 per cent in July 2020.

When mixed with opioids, benzos make it more likely someone will stop breathing during a drug poisoning. They also do not respond to naloxone, making the poisoning more difficult to reverse.

The updated death data comes on the heels of news that the federal government has agreed to grant B.C. permission to decriminalize personal possession of up to 2.5 grams of some substances in an effort to curb the harms of criminal penalties and deaths.

Based on today’s data, more than 1,500 people will die of toxic drug poisonings before decriminalization takes effect in January.

Advocates and drug users have criticized the measure as too small a step. They have also cautioned the small amounts allowed by the rules could lead to more toxic drugs as the market adjusts to a new threshold.

Two drug user advocates told The Tyee a 2.5-gram threshold for possession, down from the 4.5 grams initially requested by the province, is too low and not reflective of current use patterns.

Drug users and health advocates have said for years that separating people from the unregulated toxic supply should be the priority in order to stop deaths.

A recent death review panel convened by the chief coroner called for access to safer drug use and care.

B.C. claims more than 12,000 people have access to safe supply programs, but experts say the programs fail to provide a safe supply of pharmaceutical-grade, regulated substances to genuinely replace the poisoned supply.

In reality, only about 500 people in B.C. have access to a truly safe supply of criminalized substances through a number of small pilot projects in the Lower Mainland and Victoria.

"The panel highlighted access to a safer drug supply as the most critical life-saving need in this crisis, along with a co-ordinated, goal-driven provincial strategy and a comprehensive continuum of substance-use care,” Lapointe said.

At the time, Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson called the panel’s recommendations and tight timelines, many of which have already passed, unrealistic.

"There is no magic bullet to end the drug poisoning crisis,” she said in a statement today. “But decriminalizing people who use drugs is essential to stemming the tide of the toxic drug crisis, and to reducing the stigma around drug use.”

Vancouver, Victoria and Surrey continue to be the municipalities with the highest number of deaths.

But Northern Health’s death rate continues to be the highest in the province and is increasing. About 57.8 people died per 100,000 in that region, up from 49.3 last year.

The proportion of women dying has also increased from 20 per cent to about 26 per cent of deaths in recent months.

On average, First Nations people are about five times as likely to die of toxic drugs than their non-Indigenous peers, due to intergenerational trauma from past and ongoing colonial violence as well as limited access to primary health care. For First Nations women, that rate is 10 times greater than non-Indigenous women.

Lapointe stressed that urgent action must be taken to separate people from the increasingly toxic supply to prevent deaths.

“Our province is on the path to yet another tragic milestone in terms of lives lost,” she said. “I am hopeful that the implementation of the panel's recommendations, on an urgent basis, will stop these preventable deaths." ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: