It all started, as so many stories have in the last two years, with a COVID-19 outbreak.

On Dec. 20, 2020, in response to dozens of COVID cases at two work camps, pipeline company Coastal GasLink announced that as a “proactive measure and out of an abundance of caution” it was closing three of its dozen camps in B.C.’s northern interior to all but essential workers, sending employees home just as the holidays approached.

One month and 56 positive test results later, the outbreak was declared over. But I couldn’t help but wonder, how many cases had been transmitted to surrounding communities?

For at least one worker, a positive test result was alarming. He was swabbed just as he was about to make the hours-long drive home, and his result came the next day — after he had exposed his young adult children.

“They were a bit freaked when they found out I was positive. They isolated too, but they didn’t get sick,” says the worker, who shared his story on condition of anonymity. “Why would you wait until the last day and then test everybody? Meanwhile, it’s too late. The people that got home probably infected their families.”

In this case, the worker’s symptoms remained mild and he experienced no lingering effects. The rest of his family was fine, and he returned to work in the spring, the delay a result of public health measures imposed on work camps following the outbreak.

But he says most of the workers with whom he rode the daily shuttle between camp and the worksite received the same diagnosis after returning home.

How many other families had been exposed, I wondered?

This isn’t a story about that. (Sorry.) Instead, it is about the province’s non-response to COVID-19 information requested through its own freedom of information laws as I tried to understand and report on where infected people had gone once they left work camps and returned to their homes.

Last Jan. 4 was a Monday, and my first day back to work after the holidays. At 8:10 a.m., I filed my first freedom of information request of 2021.

“Dear intake officer,” it began optimistically, before going on to request the total number of people who tested positive for COVID-19 while spending time in work camps for LNG Canada, Coastal GasLink and Site C. While the province publicly reports outbreak numbers, I wanted total camp cases.

I also wanted contact tracing data.

“In addition, please provide the total number of positive COVID-19 transmissions in British Columbia communities that have been contact traced back to these work camps,” the FOI application continued, asking the request be directed to Ministry of Health. “If any of the records I am seeking are likely to be in the custody of another public body, please forward my request accordingly.”

Two days later, B.C.’s Information Access Operations, which processes all freedom of information requests to the provincial government, responded that the records I sought were held by the BC Centre for Disease Control, which is under the Provincial Health Services Authority. It directed me to file an FOI with PHSA, which I did before 9 a.m.

Then I waited. B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act gives government bodies 30 business days to respond.

Later that month, I received an update from PHSA that I would come to recognize as a recurring pattern: BCCDC’s communications department was preparing data that would fulfil my request. Would it be OK if communications responded instead?

I received two responses in early February, from both BCCDC’s and Northern Health’s communications departments. They were a patchwork of incomplete data, most already publicly available, for various companies, camps and time periods. Placed side by side, it was hard to believe that the two documents were provided in response to the same question.

Neither response included total camp case numbers, nor contact tracing data.

In closing my file, PHSA directed me to Northern Health. “We thought our communications department could provide a quicker answer to you than FOI, but after reviewing the request with the BCCDC, we believe that Northern Health will have the missing information that you are requesting,” it concluded.

On March 12, I submitted my request to the Northern Health Authority.

On April 9, I requested an update.

“My apologies,” came the response. “It has been brought to my attention, all requests from the media (reporters) must go through the NH Media Line.”

Now, let’s be clear: Canadians are entitled to make freedom of information requests, media and otherwise. There is nothing in the act that states that a call to a public relations team is necessary before making that request. In fact, they are two are very different processes.

Communications departments play a vital role in the dissemination of information. Their job is to respond quickly to media looking for answers on tight deadlines. But they also provide a polished response that’s significantly different from the raw data I was after.

"I’ve never even heard of a freedom of information officer requesting that you go to communications before filing a freedom of information request,” says Sean Holman, a University of Victoria associate professor of journalism and an expert in freedom of information laws.

“The whole entire point behind freedom of information is that it allows us to see for ourselves what government is doing rather than having a third-party intermediary that has a discretionary power to say some things and not say other things.”

Jason Woywada, executive director of the BC Freedom of Information and Privacy Association, says even the term “communications officer” can be seen as generous.

“Quite often, these are public relations officials. These are publicists and propagandists, in various extents, because they’re going to try and spin the information as positively as they can,” he says. “We’re not seeing any reason why communications officers should be directly involved in the release of information that is part of an FOI process.”

Yet at every pass, I was sent back to communications, with instructions like “all COVID questions from media are to be directed to Northern Health communications first.” When I pointed out gaping holes in the responses, I was told by the privacy department that it would check back with communications.

“This information was provided to you,” came one email. “Is there something further you were looking for not provided by communications?”

Um, yeah. The rest of the response. “Or am I to understand that this contact tracing data does not exist?” I asked.

Because by this point, I was seriously beginning to wonder.

In May, after a complaint to B.C.’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner, Northern Health sent me the same incomplete information that I’d received from its communications department — this time re-packaged as an FOI response.

It came with a twist.

“We have no statistical information that can be provided prior to November as [Northern Health] was directed that all COVID statistics requests should be made to [the Ministry of Health] or BCCDC,” it said.

Nearly five months after the Ministry of Health directed me to BCCDC, who then directed me to Northern Health — Northern Health was sending me back to the ministry and the BCCDC.

B.C.’s freedom of information legislation lays out the province’s duty to assist FOI applicants, including creating records where none exist and transferring requests to the appropriate body.

“You shouldn’t have to play 20 questions about where records exist,” Holman says. “That’s not consistent with what we would expect from a functioning freedom of information system.”

On June 22, I got a call from Northern Health’s privacy department. This time, I was told that while Northern Health collects and stores COVID-19 data, it’s under the control of the Ministry of Health, which approves its release.

“We were told that we’re not to be releasing any data for COVID,” the privacy officer told me.

Holman lets out a laugh when I repeat the line to him. “That’s insane,” he tells me.

“It sounds like the Northern Health Authority has a fundamental misunderstanding about what freedom of information is all about, and what the law requires,” he says. “I’m sure part of it is these agencies and ministries are under stress during COVID. I’m willing to cut them to a certain extent some slack. But after a year’s worth of trying to get data that should be readily available, my slack runs out.

“This is about an issue that falls squarely within public interest, so it shouldn’t be this difficult to get that information.”

Last month, B.C.’s information and privacy commissioner Michael McEvoy released a special report about the impacts of COVID-19 on access to information. It found that pandemic disruptions like staff redeployment, the shift to working remotely and increased workloads of those tasked with reviewing requests all contributed to delays.

In addition, it found that during the first year of the pandemic, almost all of B.C.’s health authorities experienced an increase in FOI requests — most significant of those was Northern Health, whose requests increased 91 per cent, from 55 requests in the year leading up to March 2020 to 105 in the year that followed.

Requests to PHSA also increased significantly, up 167 per cent, and requests to the Ministry of Health went up 43 per cent.

But the report also notes that delays in FOI responses pre-date the pandemic. A previous report released last year examined FOI data up to March 2020 and found that while the number of requests has increased since 2012, the number of responses received within the time allowed by the act has steadily dropped.

And while general non-compliance with the act spiked under the previous Liberal government, it crept up again in the year prior to the pandemic, with the on-time response rate at 83 per cent. “This means that in the remaining 17 percent of the cases, government delayed responding without legal authority,” the commissioner noted. The emphasis is his.

If staffing is the issue, Woywada says, the province is legally obligated to provide those resources. “Each ministry is supposed to have the resources to meet its requirements under the act, full stop,” he says.

Keep in mind, he adds, that every time someone seeking information through FOI agrees to the province’s request for an extension, those delays aren’t captured in timeliness reports because they don’t technically contravene the act — and requests for extensions are becoming increasingly common.

“Extensions are to be granted in exceptional circumstances,” Woywada says. “If every request receives an extension request, that’s no longer an exceptional circumstance.”

And while the commissioner’s report showed a slight decrease in complaints to its office, Woywada says quantitative data in the report doesn’t mesh with the anecdotal evidence he’s hearing from those using the system.

“We hear from other reporters that are talking amongst themselves... and the qualitative analysis is telling us that there’s a problem here,” he says. “It’s almost as though they’re trying to test how little information they can release to the public and maintain trust. That’s really problematic.”

Not all information is releasable under B.C.’s freedom of information laws. There are exceptions for things like policy or legal advice to government and information that could be harmful to law enforcement, public safety and personal privacy.

But if my request contravenes any section of the act, that has never been communicated to me.

Nearly 10 months after filing it with Northern Health — and a year after making it to the Ministry of Health — it remains in limbo. Currently, my complaint sits with B.C.’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner.

While it’s never been made clear to me which agency should respond to my request, a decision by B.C.’s Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner may shed some light on the province’s approach to releasing pandemic data.

In 2020, three First Nations made a formal complaint to the OIPC over the lack of information about nearby COVID-19 cases. The Heiltsuk Tribal Council, Tsilhqot’in National Government and Nuu-chah-nulth Tribal Council argued that under Section 25(1) of the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act, the province must disclose the information because it’s in the public interest.

In his December 2020 decision, McEvoy quotes provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry, who says that information collected under the Public Health Act “is under my control” and that she is “responsible for the policy and governance framework respecting, the collection, storage, use and disclosure of communicable disease information.”

The ministry argued that, in an emergency, B.C.’s Public Health Act overrides freedom of information laws.

“[The] decision to disclose information relating to managing the risk of transmission of COVID-19 is ultimately at the discretion of the PHO — she is given the authority, in her role as the senior public health official for the province, to determine whether disclosure is in the public interest,” it stated.

But the commissioner disagreed.

While ultimately siding with the province, saying it was providing enough information to mitigate public health risk, the commissioner said arguments positioning B.C.’s provincial health officer as gatekeeper for all COVID-19 data were unsubstantiated.

He pointed to Section 79 of B.C.’s Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (now Section 3(7) following a controversial overhaul of the act in October), which states that when information laws are at odds with other provincial acts, information laws prevail.

The commissioner also confirmed that the Ministry of Health was best suited to respond to pandemic-related freedom of information requests and that any override by the health act was “limited in scope.”

Woywada says overrides to the Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act do exist under B.C.’s Emergency Measures Act, which could affect the flow of information. But the province lifted its state of emergency in June.

“Emergencies are meant to be temporary, and the concern we have is this government is increasingly operating like it’s in perpetual emergency now, and that’s deeply concerning,” Woywada says. “To hear from a health authority that they aren’t releasing any COVID-19 information at all is problematic, because how can the public in that health authority trust the information that they’re being given when they can’t verify it?”

In fact, Holman adds, an emergency is the most important time to release information. When the public is left to rely solely on information the government chooses to release, some will turn to other sources, fuelling things like conspiracy theories and disinformation.

“Information is the one thing that you don’t want to stop flowing,” Holman says. “Information is the one thing that people desperately need in a pandemic. The fact that government has failed to recognize that and headed now in the opposite direction with its recent freedom of information amendments means that the NDP fundamentally misunderstands what a democracy should be all about.”

He adds that information is “all about control and certainty.” It helps us make decisions that keep ourselves and our families safe, particularly during times of uncertainty. Whoever holds that information also holds control and certainty, he says.

In June, I filed a parallel request with Northern Health, this time asking for internal government communications — rather than data — about COVID-19 cases at industrial work camps. Once again, I was told that “the privacy office is not releasing information regarding COVID-19 at this time,” but that it would be “assisting” communications with my response.

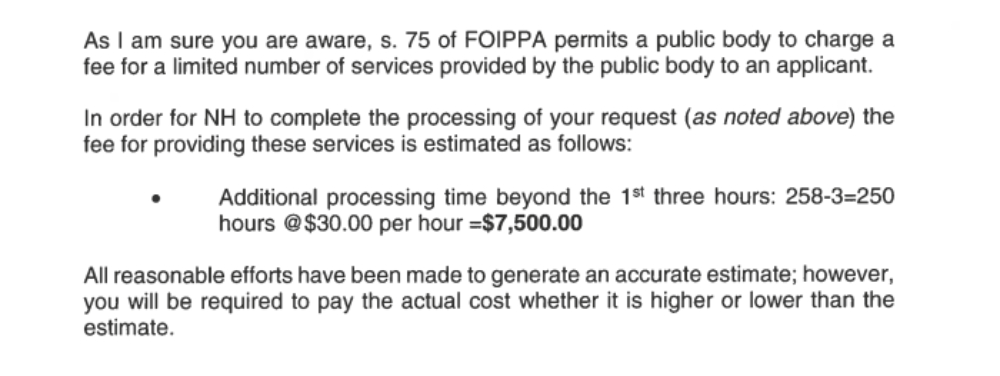

In October, well beyond its extended deadline, Northern Health told me my second request was too broad and estimated it would cost The Tyee $7,500 to retrieve the records. That fee estimate is now also with the commissioner.

The Ministry of Health declined repeated interview requests for this story.

In response to my emailed questions about the FOI process, it sent a detailed list of where COVID-19 data is available to the public — daily information bulletins, media availabilities and the BCCDC COVID-19 dashboard, to name a few.

It told me that last year the ministry responded to nearly 6,000 media requests — most of them related to COVID-19 — and did 420 interviews, produced over 4,000 statements and made 360 announcements.

“British Columbians can also access information through a freedom of information request,” it advised. “We are committed to continuously improving the FOI system so people in B.C. have timely access to information that they need and have been working to help people get their records faster.”

When pressed, the ministry confirmed that pandemic measures do not give provincial bodies the power to prevent the release of information about COVID-19.

But after multiple email exchanges, it still hadn’t answered my main question.

“Why am I being told that direction from the Ministry of Health is to not release any COVID-19 data through freedom of information requests?” I asked again.

The ministry did not respond. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Coronavirus, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: