As British Columbia records more toxic drug deaths than ever, the minister responsible defended what experts and advocates have called a delayed and inadequate response to B.C.’s six-year-old public health emergency.

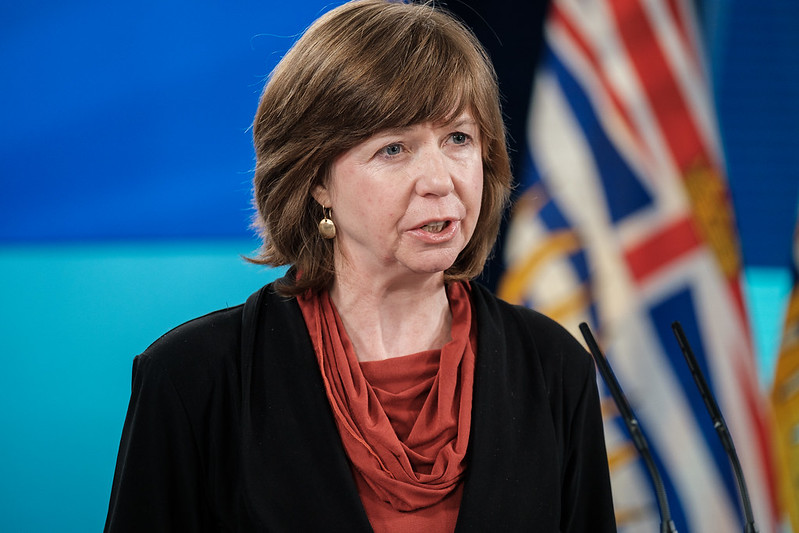

“We are in two public health emergencies, compounded by decades of stigma and isolation and alienation from health care from some of the most vulnerable people in our society,” Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Sheila Malcolmson said in an interview with The Tyee Thursday.

“We are making up lost ground.”

The same day, the BC Coroners Service confirmed 201 people died of poisoned drugs in October, the highest number ever.

And after 10 months, 2021 is already the second consecutive most fatal year on record with 1,782 lives lost. Last year, 1,765 people died.

In the nearly six years since toxic drug deaths were declared a public health emergency, the rate of deaths has doubled to 41.2 per 100,000. More than 8,500 British Columbians have died in that time. Toxic drugs are the leading cause of unnatural deaths in B.C., more than car accidents, homicide and suicide combined.

Chief Coroner Lisa Lapointe said the slow response to the toxic drug crisis will be a “stain on our province for decades to come.”

“Simply put, we are failing,” Lapointe said Thursday. “This crisis is not going to turn itself around, this crisis needs some true intervention on a meaningful provincial scale.”

BC Green Party Leader Sonia Furstenau again called for an emergency all-party legislative committee to expedite legislation “to end the brutal loss of life.”

“That would take politics out of the process, and we can be bold,” said Furstenau in an interview, noting a similar committee facilitated a rapid government response to COVID-19.

The BC Liberals also renewed their calls for more addiction treatment beds and for a similar all-party committee to take immediate action to stop deaths.

"We need action, concerted and focused action, that attacks the problem — not empty words," said MLA Trevor Halford, Opposition critic for mental health and addictions in a Thursday news release.

Malcolmson acknowledged there is much more work to be done. But she did not indicate her ministry would be changing course despite the evidence its current strategy has failed to curb deaths.

Without any budget to administer its own programs, Malcolmson’s ministry has also been criticized as a way to deflect criticism from the Health Ministry, which is ultimately responsible for administering overdose prevention programs through health authorities.

Asked whether the current number of deaths represented a failure in her mandate or warranted her resignation, Malcolmson did not directly answer the question and ended the interview.

“The fact that the drug toxicity increases are outpacing the ability of our health-care system to implement solutions and set up resources within health care is tragic, and something that just further reinforces our determination to do more,” she said before hanging up.

Furstenau said Malcolmson needs to be transparent about how she is measuring success in her ministry’s response, and what accountability will look like if she does not achieve it.

If its main metric is the number of toxic drug deaths decreasing, then “no, the ministry has not achieved its goal,” she said.

Lapointe said new and potent combinations of criminalized substances like fentanyl, carfentanil and benzodiazepines continue to escalate the crisis and increase deaths.

Lapointe has called for rapid access to safe, regulated supplies of criminalized substances, known as safe supply, to prevent deaths by separating people from the increasingly toxic drug supply.

“We have not seen a rollout of safe supply on a scale commensurate with the risk to health and safety in our province,” said Lapointe, noting that co-op models, compassion clubs and other solutions need government support to reach as many people as possible.

“There is intent, there is good will, there are plans. To my mind, they’re not urgent enough.”

Malcolmson pointed to the province’s expansion of prescribed safe supply, which it began in March 2020 in response to the pandemic and said it would expand again in September 2020.

But that promised expansion in the program did not come until 10 months later in July. In that time, at least 1,694 more people died of toxic drugs.

Drug user advocates and experts said the new measures were too small and too slow.

Malcolmson said the benefits of the expanded program would be seen in the “weeks and months” ahead.

Furstenau said blaming delays on “lost ground” before the government’s time in power would be acceptable “maybe in year one, but not in year five.”

Lapointe, whose agency’s mandate is to investigate the cause of death and make recommendations for death prevention, declined to place blame on any individual or organization.

But she said without widespread access to low-barrier safe supply, other government efforts to decriminalize personal possession of substances and expand treatment and recovery options for people with substance use disorder will not end this crisis.

“As long as people are dependent on the for-profit, unregulated illicit drug market, their lives are in jeopardy,” said Lapointe. ![]()

Read more: Health, BC Politics

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: