Joanne’s gnawing anxiety would start as soon as her workplace, the Hotel Canada in downtown Vancouver, came into view. It’s a looming seven-storey building with small rooms and shared bathrooms, the type of hotel known as a “single-room occupancy hotel,” or SRO. The century-old buildings dot the city’s downtown, housing some of Vancouver’s poorest and most marginalized people.

Joanne was a front-desk clerk at the hotel at 518 Richards St., a job that includes monitoring the front door of the building, checking on tenants every hour, responding to emergencies and dealing with drug overdoses.

She liked much of the work with the tenants, even though most struggled with substance use and mental illness and things could quickly spin out of control. Once she had a gun pulled on her, and sometimes tenants would call her derogatory names.

But Joanne said the hardest thing was feeling like she had no support from her co-workers.

It never really let up. One tenant with mental health issues repeatedly set fires in his room — in one case, twice within 45 minutes — but Joanne said she wasn’t able to respond to attempt to put the fire out because her co-worker was incapacitated after using drugs and she couldn’t leave the front desk.

“My co-worker would disappear — she’d turn off the walkie talkie,” Joanne said. “So I was by myself.” All she could do was wait for the fire department to arrive.

“And then I had an overdose that we had to deal with where I kind of froze a little bit, because it was somebody I know. And then my co-worker never let me live it down.”

After six months of dealing with post-traumatic stress disorder and severe anxiety, Joanne left her job in early 2020, deciding the stress wasn’t worth it.

“I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m not risking my life for this — is this worth 14 bucks an hour?’” she said.

Today, Joanne says she can’t leave the house when it’s dark, and whenever she hears ambulances or police sirens, “I freak out.”

Working in any SRO is challenging. The residents are almost all dealing with mental health and substance use issues and living in extreme poverty. Supports — in the community and within the buildings — and funding are inadequate.

But other workers have similar stories about SROs managed by Atira Property Management Inc., a subsidiary of Atira Women’s Resource Society. They say the buildings are poorly maintained and cleaned, workers don’t have enough training, and employees are paid less than staff doing similar work at other organizations.

Janice Abbott, the CEO of Atira Women’s Resource Society, says the problems at the buildings stem from deeper issues: drug prohibition, a broken housing and mental health system, and trauma and poverty.

Residents in the buildings have a wide range of challenges that make life difficult for them and affect relations with staff, she said.

“In addition to folks who are struggling with substance use, people are struggling with what it’s like to be chronically poor over a long period of time, all of the health conditions that arise as a part of poverty and how that impacts your mental wellness,” Abbott said.

When Bronwyn Elko worked at another Atira-managed SRO, Carl Rooms, from 2009 to 2015, bathroom doors didn’t lock and sewage water frequently backed up into shower drains, she said. A male co-worker belittled female tenants, wore a knife to work and repeatedly “joked” he would help Elko commit suicide. Although Elko repeatedly reported the problems to the company, she said the situation never improved.

On most of her shifts working at the Arco Hotel in 2020, Jennifer Hall Russell said her co-workers would be passed out after using drugs, meaning she was mostly working alone in the 55-unit building.

Kida Steel showed up to one shift at Carl Rooms in 2019 to find that the master keys for the entire building had disappeared from the office, likely taken by a tenant or building guest.

“I didn’t know if there was a crime in progress, if someone was being confined,” said Steel, who refused to work that shift because of safety concerns.

Atira denies the situation was unsafe, and a WorkSafeBC arbitrator ruled in favour of the employer — a decision that Steel plans to appeal. Steel refused work on two other occasions when she believed it was unsafe, but the arbitrator also ruled against her in those cases.

Nicole, who worked at the Gastown Hotel until April, said it was common for some of her co-workers to swear at residents and call them names like “stinky bitch.”

“The fact that the workers are rude, that they swear at tenants, yell at them, is a huge thing for all the tenants, because everyone’s had some kind of trauma involving that,” Nicole said. “And it’s not an isolated thing.”

In the Gastown Hotel on Jan. 31, a front-desk clerk working alone overnight attempted to provide first aid to one of two victims of a stabbing, while fending off attacks from the assailant. One man, Jeremy Greene, died in the attack; a year earlier, tenant Tonya Hyer had been beaten to death in the hotel.

On March 18, 24-year-old Shania Paulson died after being shot in the Arco Hotel during a dispute over drugs. And on July 29, 40-year-old Michael Bailey was shot and killed at the London Hotel.

After four homicides in 18 months and more than a year of working through the stresses of the COVID-19 pandemic and a raging overdose crisis, current and former employees are speaking out about conditions inside SRO hotels operated by Atira Property Management Inc.

The workers The Tyee talked with said they knew the work would be challenging and involve mental health crises and overdoses. Most understood Downtown Eastside street culture.

It was the lack of support from co-workers and management that made the job dangerous, demoralizing and hard to do, they said.

“It has to stop somehow,” Nicole said. “It may be better training, maybe hiring people that are a little more qualified, because none of us are qualified to deal with the stuff that we deal with every day in these places.”

Eight employees share stories

The Tyee spoke to eight current and former APMI employees for this story. All are women, and five still live in the Downtown Eastside. The Tyee is using pseudonyms for some because they still work at Atira or other social service agencies that do similar work, and they fear they could face employment repercussions for speaking to the media. The Tyee confirmed the women had worked for the company by reviewing paystubs, tax records, work emails or WorkSafeBC documents.

The eight employees described working in buildings that were dirty and poorly maintained. Several said they frequently worked alone in the SROs, where severe mental health issues, disputes over the illicit drug trade and the frustrations of poverty can boil over into violence. Two of the workers advanced to management positions while four worked as front-desk workers the entire time they were employed with Atira Property Management.

The employees said despite the challenges and dealing with some extremely difficult residents and visitors, they loved parts of their job, especially working with tenants, and had good working relationships with some co-workers.

But they said staff are poorly paid and have little training, and many of their co-workers are frequently unable to perform their duties because they use drugs while on the job. The employees who spoke to The Tyee felt their concerns were not being heard and didn’t feel supported by their employer; some also said they didn’t feel supported by their union.

Several employees said they are still affected by the post-traumatic stress they believe was acquired or worsened while working at the buildings.

Abbott says the work is challenging and has called APMI employees “heroes” for the difficult work they do. Around 80 per cent of residents in the buildings are “struggling with substance abuse,” she said.

Atira also has a mandate to hire 80 per cent of its workforce from the Downtown Eastside community — an attempt to lift people out of poverty, Abbott said, and many of the people who work at the buildings also have a history of current or past substance abuse. Atira planned to hire eight people who are moving into its buildings from the Strathcona Park encampment as staff in their new homes.

It’s also common for workers to live at other APMI-run SROs.

When Atira learns of problematic substance abuse at work, Abbott said the organization works with the employee to treat addiction as a chronic health condition. She said Atira takes into account the amount of trauma that people have gone through since the overdose crisis worsened in 2016 and recognizes that trauma is a trigger for relapses.

Atira has “robust internal complaints processes that provides staff the opportunity to raise concerns both on the record and anonymously,” Abbott said. Employees can also raise concerns through their union — the BC General Employees Union — or WorkSafeBC, she said.

The Tyee submitted a freedom of information request to WorkSafeBC for any orders, close calls or workplace injuries for four Atira-managed buildings in 2020 and received information on just one incident. The incident occurred at Dominion Hotel in February 2020 and involved a tenant’s behaviour, but full details of the incident are redacted for privacy reasons. After investigating, WorkSafeBC found that APMI did not conduct a preliminary or a full investigation into an incident that had the potential to cause serious injury to a worker and ordered the company to submit a report detailing how the employer would prevent “such events” in the future. WorkSafeBC staff later wrote that they were satisfied with APMI’s compliance with that order.

Abbott acknowledged employee complaints about cleaning and maintenance. She said it’s an ongoing challenge to maintain the aging buildings, especially considering the number of non-tenants who live in the buildings or visit and cause constant damage to toilets, doors and other parts of the buildings.

But employees say they have repeatedly tried to raise such issues with the company, and nothing ever seems to change.

Stephanie Smith is the president of the BCGEU, which represents Atira Property Management employees. She says the union isn’t aware of any problems at the company that workers at other supportive housing sites don’t also experience but said the APMI collective agreement does include detailed language on bullying and harassment.

“One of the things that was brought to us by the members at Atira and was identified as a real issue for them was bullying and harassment,” Smith said. “It is in other sectors as well, but we were able to negotiate really strong and very specific language around bullying and harassment in response to the issues that were being raised by workers there.”

Housing of last resort

In Vancouver, a city with some of the most expensive real estate in the world, SRO hotels are the housing of last resort for people who haven’t been able to find housing anywhere else because of poverty, substance use or severe mental health issues.

SROs were built at the turn of the 20th century as hotels to house seasonal labourers and travellers. Narrow hallways lead to tiny 100-square-foot rooms, and most rooms don’t have their own kitchens or bathrooms — 20 tenants on a floor will often share one toilet. The buildings are concentrated in the Downtown Eastside and other parts of downtown Vancouver.

In the mid-2000s, with SRO buildings rapidly changing hands as real estate prices rose, entire buildings were regularly being illegally evicted or ordered to vacate because of building safety issues. The B.C. government began buying the buildings in an attempt to preserve badly needed affordable housing.

Most are operated as supportive housing, with staffing and other programs to help tenants stay housed. It’s key to current municipal and provincial strategies to house growing numbers of homeless people in B.C., and governments depend on social service agencies to operate the housing.

But critics say the supports are inadequate, especially given the mental health and addiction issues of many tenants.

Atira Women’s Resource Society operates shelters, transition homes and permanent housing for women across the Lower Mainland. Canada Revenue Agency filings show AWRS had $45.1 million in revenue in 2020, with $34.3 million of that coming from government funding.

Atira Property Management, a for-profit property management subsidiary of the society, manages SROs, both private and government-owned, as well as condos and other rental buildings. The property management company was created in 2002, and by 2015 was managing 90 buildings with a staff of 280.

A 2015 profile of Abbott in Business in Vancouver described how she wanted to start a for-profit business that would “expand Atira’s funding beyond fundraisers and government grants.” In the story, Abbott described how she decided to start a property management company because of her organization’s existing expertise in running non-profit housing for women.

In 2007, APMI began managing a portfolio of SRO buildings that had been bought by BC Housing. According to Abbott, the buildings “were offered to other non-profits, but those non-profits turned them down because of their condition.”

Abbott is married to Shayne Ramsay, the CEO of BC Housing — an agency that has frequently contracted Atira to operate housing and handles complaints from tenants. BC Housing says it protects against any conflict-of-interest concerns by “a rigorous conflict of interest declaration and conflict screen protocol.” BC Housing says Ramsay is not involved in any decisions about Atira projects, including contracts, approval of projects, reviewing operations or any other issues.

Today, Atira Property Management Inc. operates 20 SRO buildings, far more than any other non-profit housing provider; 11 of those buildings are owned by the B.C. government. PHS Community Services Society runs seven SRO buildings, while Lookout runs four and RainCity runs two.

It’s an extremely challenging type of housing to operate. Tenants or other visitors often deal drugs in the buildings, and being involved in the illicit drug trade can lead to situations where tenants who deal are being threatened or attacked inside the buildings. Overdoses are common.

The buildings also house people with severe mental health issues who sometimes resist pest control or having their rooms repaired, or threaten to harm themselves or others. Some tenants are very elderly, while others have physical or cognitive disabilities. Even though the rooms are just 100 square feet, they often house the guests or partners of tenants as well.

A 2013 study of 293 SRO residents found that 45.8 per cent had a neurological disorder, half of the participants suffered from psychosis, 18 per cent were HIV positive and 70 per cent had been exposed to hepatitis C.

“Atira is a very experienced housing operator that works with a range of clients, many who have high needs, have faced trauma and may be experiencing multiple health issues,” Laura Mathews, manager of media relations for BC Housing wrote to The Tyee in an email. “The work their staff do can be complicated and challenging.”

But Mathews also said BC Housing is concerned about residents’ recent complaints about the buildings, which have included concerns about cleanliness, delayed maintenance and rat infestations. BC Housing says current residents can email their concerns to the agency.

A 2012 CBC investigative story raised concerns about the publicly owned SRO buildings that were operated by Atira Property Management: staff and tenants complained the buildings were filthy, poorly maintained, and that employees were often under the influence of drugs while on the job.

Many of the publicly owned buildings have since been renovated with government funding, but problems persist. Despite being completely renovated in 2014, including getting new pipes, the Gastown Hotel still has plumbing problems and frequent floods, according to tenants and staff. A Tyee investigation found persistent plumbing problems at the London Hotel meant many bathrooms, sinks and showers haven’t worked throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. The hotel is scheduled to close in September so the private owner can repair the pipes.

Andrew Drury advocates for people on bail and probation, a role that involves helping his clients navigate services in the Downtown Eastside, including housing. Drury said other supportive housing agencies also have problems with working conditions and staff not feeling supported by their managers, but he said SRO buildings managed by APMI are particularly understaffed, not cleaned properly, and repairs seem to be slow.

Drury said he’s found that tenants don’t get much help from staff when there are problems with their rooms.

“The tenant will end up needing to do things for themselves. If they go to staff to get something done in their rooms — repairs, or clean up in a washroom — it’s probably not going to get done,” Drury said. “But if they have someone advocating for them in the community, it will get done.”

In some buildings, including the APMI-operated St. Helen’s Hotel on Granville Street, tenant support workers are stationed in an office on each floor of a building during the day, a system that Drury said works better because staff are aware of what’s happening on each floor. He said inter-agency partnerships — where one agency, such as PHS, Lookout or Atira, operates a building, but another organization is doing outreach in the building with health or tenant support teams — also seem to work well, because the organizations keep each other accountable.

Drury singled out the London Hotel as having some of the worst problems. He said BC Housing tends to put vulnerable people who have been recently homeless into the building, where they are often bullied by other residents or get their rooms taken over by drug dealers who live in the building.

Abbott said the SRO hotels are intended to support people facing those challenges.

Maintenance issues and low pay

The City of Vancouver’s Rental Standards database shows that in December, nine out of the top 20 buildings with the most building safety and condition issues were operated by APMI or Atira Women’s Resource Society; eight were SRO buildings located in the Downtown Eastside or downtown Vancouver.

By April, the number of Atira buildings in the top 20 had dropped to five, indicating many of the issues identified in 2020 had been resolved. No other non-profit housing provider had more than one building in the top 20 group.

Data on police calls to SROs in 2020 show the Carl Rooms, operated by APMI, had the most calls per unit, at 12.2, followed by 7.7 for the Hotel Irving, operated by PHS Community Services Society. Six out of 10 of the buildings with the most police calls are operated by APMI, while two are operated by PHS and two are operated by RainCity.

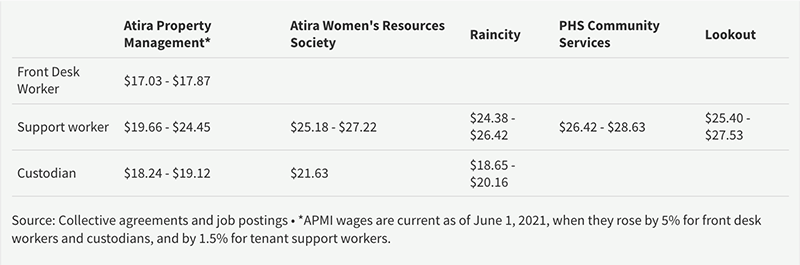

APMI also pays its staff less than other non-profit housing operators, including its own parent organization, Atira Women’s Resource Society.

Support workers at Atira Property Management Inc. start at $19.66 per hour under their BCGEU contract. That’s 28 per-cent lower than the starting wage for the same role at the parent Atira Women’s Resource Society. RainCity, Lookout and PHS Community Services, which all manage SROs, pay at least 24 per cent more as a starting wage for support workers.

Custodians at APMI start at $18.24, 16 per cent less than their counterparts at Atira Women’s Resource Society. The starting wage at RainCity is two per cent higher.

And front-desk clerks at APMI, responsible for screening visitors, monitoring tenants and responding to emegencies, start at $17.03 an hour, rising to $17.87. Before a union-negotiated pay increase that kicked in on June 1, front-desk clerks made between $16.22 and $17.02 an hour. Other supportive housing providers pay significantly more.

While APMI workers are represented by the BCGEU, workers at Atira Women’s Resource Society, PHS Community Services, Lookout, RainCity and the non-profits Kettle Society and Bloom Group are part of a common collective agreement between a number of unions and the Health Employers Association of BC.

When The Tyee asked whether this pay disparity makes it difficult to retain staff, Abbott initially denied that APMI pays less than other organizations. She then said that because the staff chose to organize with the BCGEU, The Tyee would have to direct questions about the collective agreement to the union.

“Interesting that Ms. Abbott wouldn’t address this,” Danielle Marchand, press secretary for the BCGEU, wrote in an email to The Tyee.

“The supportive housing sector is complicated in terms of funding sources, sectoral agreements and job classifications — all of those factors impact wage disparities between agencies. Ultimately the BCGEU’s position is that workers in the same sector doing the same work should have parity in wages, benefits and working conditions. We will continue to work with our members towards that goal.”

Worker Nicole said the low wage — about $650 a week to start — is part of the reason that many front-desk workers continue to live in SROs themselves. Employees are not allowed to live in the buildings they work in, but it’s not uncommon for front-desk staff to go to work at an APMI-operated building and come home to an APMI SRO.

Because it’s easier to transfer to other housing within the same supportive housing provider’s portfolio, some workers who are Atira tenants said they felt trapped in the Atira system.

Abbott said there’s a shortage of housing that allows people to move out of supportive housing when they no longer need it.

She said APMI pays a relatively low wage (now starting at $17.03 an hour) to front-desk staff because Atira has a mandate to hire around 80 per cent of its staff from the Downtown Eastside community, and the front-desk jobs are unofficially considered “peer” positions for people from the community who have barriers to employment.

“If you want to start… change for people, having the opportunity to earn an income, having health and dental benefits, having paid sick time, having a pension all count,” Abbott said.

Peer workers are people who often have barriers to employment, but whose lived experience helps them relate to people who have experienced homelessness or substance use. They’re most commonly hired at safe drug consumption sites, and the work is a way to gradually introduce people back into the workforce. Recently, some peer workers at overdose prevention sites have spoken out about stipends that fall below minimum wage, unstable work hours and not receiving the same benefits or protections as full employees.

Andrew Ledger is the president of CUPE 1004, which represents workers at PHS Community Services Society and has been working to unionize peer workers at PHS.

He said peer workers have become more common in the past five years, but at PHS they are usually hired for harm reduction work, not employed as front-desk workers in supportive housing buildings.

“They bring a unique skillset that is absolutely needed,” Ledger said. “But unfortunately, that has come with a discounted rate of pay and that’s across the board, whether it’s the health authority or a community services society.”

Abbott describes the front-desk workers at Atira Property Management as “basically peer workers.” They are still members of the union and have full pay and benefits, she said.

The employees The Tyee spoke to were surprised to hear their jobs described as peer positions. “I’m not peer support, nor have I ever heard anyone called that in the office,” said Nicole, who made $17 an hour after four years on the job as an overnight desk clerk at the Gastown Hotel. She recently got a job working as a front-desk worker at another housing provider and is now making around $25 an hour — $8 more than when she worked at APMI.

Elko also said she had never heard her job referred to as peer work and called it a “slippery ruse.”

“I suspect it’s a convenient way to justify paying people less,” she said. “Atira front-desk clerks do pretty much the same job as desk clerks who work for other agencies — and last I heard, they were also paid more.” Elko said the job includes acting as a first responder, a security guard, doing basic building maintenance and helping high-needs tenants.

“I spent a lot of time listening to the problems of tenants [and staff] and trying to resolve their issues,” Elko said. “I also spent a crazy amount of time cleaning up raw sewage coming up through the toilets and shower drains, without proper safety equipment.”

Abbott said workers currently have access to protective safety equipment, and at the time Elko worked at Atira, she could have reported her concerns to her shop steward, the health and safety committee or WorkSafeBC. Elko says she did report her concerns, but they were never dealt with to her satisfaction.

According to a recent APMI job posting, front-desk workers are responsible “for maintaining the safety and security of the premises, responding to tenants’ questions, answering the phone and responding to questions/taking messages from callers, undertaking hourly floor and room checks; responding to emergencies, including administration of naloxone,” a drug that reverses opioid overdoses.

Abbott said it has been difficult this year to find enough staff at APMI SRO buildings, with many workers absent because of COVID-19 exposures or cases, or because they are dealing with the loss of friends or family members.

While APMI has funding to staff overnight shifts with two employees, many employees are working alone at night because it’s been difficult to find enough staff.

But that labour shortage hasn’t stopped APMI from taking on contracts for more buildings, as BC Housing spends millions to acquire emergency housing to address rising homelessness during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since the spring of 2020, Atira Property Management has received contracts from BC Housing to operate the former Howard Johnson at 1176 Granville St. and the Patricia Hotel at 403 E. Hastings St.

Chaos at Carl Rooms

Following a rough patch in her life when she hadn’t been able to find work for several years, Bronwyn Elko was excited to get hired at Atira in 2009. The organization’s mission to end violence against women appealed to Elko, who had previously worked at an organization that runs transitional housing for women in the Yukon.

At first, Elko pinned the chaotic working environment on the fact that Atira Property Management Inc. was new to running SRO buildings. But as time went on, she got more and more frustrated. Her pleas for supplies to help organize the building’s bundle of keys and reports of broken doors, lights and constant plumbing problems never seemed to lead to any improvement.

Elko said the building wasn’t a safe place for workers or for residents, especially women.

“There was a lot of sexual harassment,” she said, with both tenants and co-workers facing harassment from some staff. “There was a lot of staff coming to work, doing drugs, being high on the job or disappearing on the job.”

Abbott said the company has a comprehensive harassment in the workplace policy and all complaints of bullying and harassment are thoroughly investigated.

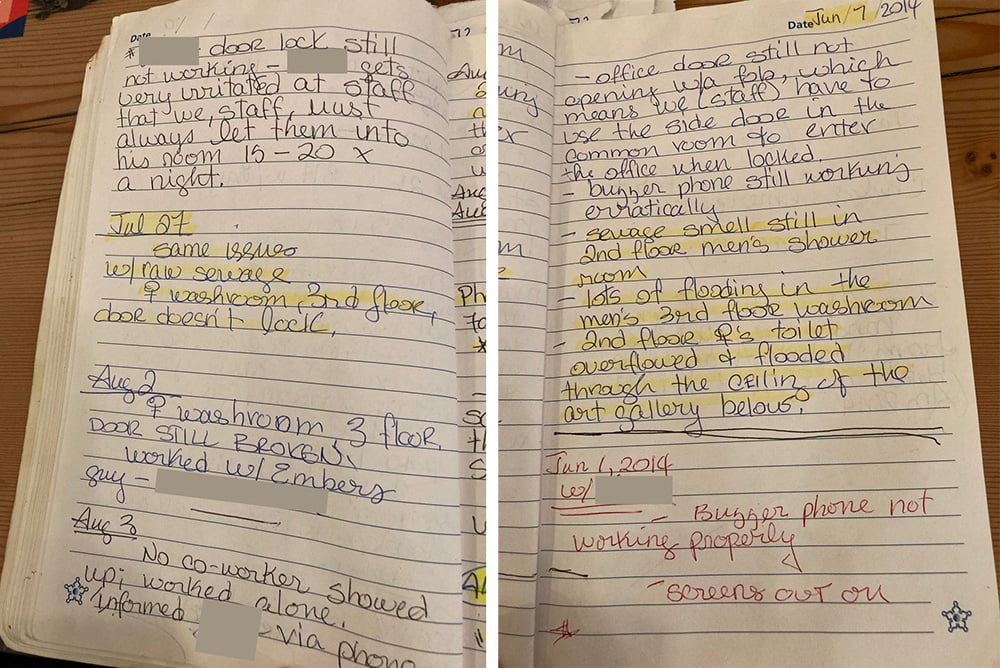

In a diary spanning January 2014 to March 2015 that she shared with The Tyee, Elko documented a litany of building maintenance problems. From Jan. 12 to March 9, 2014, the front door wasn’t closing and locking properly. From Jan. 19 to June 28, the front door buzzer, which tenants need to use to be let into the building, wasn’t working at all or only worked sometimes. Plumbing problems plagued the summer months, with constant floods and sewage backing into shower drains. Staff were exposed to sewage and afraid the air might be contaminated and make them sick.

“I wrote in the log re: second floor women’s washroom flooding with raw sewage again,” Elko wrote on July 25, 2014. “This is a chronic issue at Carl Rooms which has gone on for years.”

Abbott said there have been major problems with the plumbing at Carl Rooms for years, and it is “beyond the scope of day-to-day maintenance.” Abbott said BC Housing, the owner of Carl Rooms, is responsible for addressing the plumbing problems.

In January 2014, Elko was hit, pushed and threatened by a woman who lived in the building; her co-worker didn’t do anything to help, calling the incident a “catfight” when she asked him why he didn’t do anything to support her during the tense interaction, according to Elko. A video of the incident, which The Tyee has viewed, shows the co-worker sitting in an office chair while the tense interaction between Elko and the tenant took place.

A year later, Elko said she encountered bloodstained clothing and drug paraphernalia in one of the women’s bathrooms. The lock on that bathroom was repeatedly broken, and both male and female tenants had been assaulted there, Elko said. “People got hurt in that washroom.”

The blood in the bathroom was a common enough sight in the hotel, where people often used drugs in the shared washrooms. But that day, the sight of the bloody clothing triggered a traumatic response in Elko, which she traces back to feeling unsupported by her co-worker.

Elko would never work at Carl Rooms again, and continues to deal with the post-traumatic stress disorder she says was caused by working at the building and has prevented her from working since.

When she worked at the company, Elko said she was a member of the Occupational Health and Safety Committee and frequently raised concerns about safety with both the union and management, sending emails to both her manager and Abbott about maintenance and safety issues.

She said her messages brought little change, and she didn’t feel supported by the union.

In one email from August 2015, the manager of Carl Rooms wrote to Elko that the third-floor women’s bathroom had been fixed and the entire doorframe replaced — and then the door was broken again a week later.

“I have serious doubts that the door can remain repaired as long as there are no cameras pointed at those bathroom doors to see who’s doing the damage,” the manager wrote. He went on to say there had been no new cameras installed, despite his recommendation in a work site violence risk assessment sent to WorkSafeBC.

“We made it clear [to WorkSafeBC] that it could only be done with proper funding from BC Housing. There is absolutely no way Atira can just foot that bill,” he wrote.

Drury said conditions at Carl Rooms have improved recently, which he attributed to inter-agency partnerships serving residents working well.

Concerns about training

While the BCGEU’s Smith said the concerns the union hears from APMI workers are similar to the issues faced by other workers in supportive housing, employees who have experience working at other organizations say not all supportive housing providers operate the way APMI does.

Julie left APMI in the summer of 2019 after a year and a half on the job. She says she quit after being sexually harassed for months by a supervisor who had offered her a management position. (She never reported the harassment to the company, fearing the consequences if she spoke up.)

Julie went on to work at RainCity, which operates supportive housing buildings and shelters, including some SRO hotels in the Downtown Eastside. While working there, Julie said co-workers also used drugs on the job. But she said the response from the company was different from what she experienced while working at Atira.

“One great thing with RainCity is, when they get wind of this, they actually act upon it. And they don’t discipline the staff, they actually offer the staff support,” Julie said.

Abbott said Atira offers help to employees who relapse and need help dealing with substance abuse.

Abbott said Atira used to contract the Open Door Group to do training but is now in the process of moving to a training program designed in-house. She said Atira hopes to roll out the training using iPads that employees will be able to use while they’re at work to complete the training modules online.

Kimberly Corbett, now the manager of a building run by Atira Women’s Resource Society, said she managed the Gastown Hotel until 2018. She said she loves working at Atira and said APMI workers are well-trained.

“All the front-desk staff go through… basic security training,” Corbett said. “They all get first aid; they all get non-violent crisis intervention training. And I know this because I’m a facilitator and I trained them all.”

But other former employees said that in their experience, that was not the case.

Hall Russell said she worked her first shift without any training at all, including how to administer the opioid overdose reversal drug naloxone.

Joanne said she did not have naloxone training when she started working at the Hotel Canada and worked for several weeks before attending training sessions. She said she went online to find resources to teach herself how to administer naloxone.

Nicole said she had sent an email to Abbott, asking for better training for staff.

Former workers lobby for higher pay, more training

Hall Russell worked at five APMI-operated SROs as a relief front-desk clerk between the summer of 2020 and February 2021. She said she liked working at the Arco and Carl Rooms, but at other buildings, she felt unsafe the entire time.

At the Cosmopolitan, a filthy and mostly empty building owned by the Central City Foundation, Hall Russell said it was impossible to know who actually lived in the building and who to let in when she worked there in the fall of 2020. People who didn’t live in the building frequently used the rooms, and the risk of those people overdosing was high. At the Winters Hotel in Gastown, there was a constant threat of violence because tenants who were involved in the drug trade had angered another dealer.

The Central City Foundation says the Cosmopolitan was “infiltrated and taken over by illegal tenants” in 2019, but as soon as the organization learned about the situation, it took steps to take back the building and repair the damage.

Hall Russell said it’s important to hire people to work in the buildings who understand substance use and the life experiences of tenants, and don’t further stigmatize residents.

She said it’s a “nice idea” to hire from the community, but “I don’t believe that it is in anyone’s best interests to have an entire building staffed by people from the community,” she said.

“They need to alter their hiring practices so that there are people in the buildings who have actual training and expertise in these types of situations… and they need to pay people more than $16 an hour.”

Elko said she thinks the constant maintenance problems in the hotels lead to more frustrations and more conflicts between tenants, and between tenants and staff.

Given the state of the buildings and the high needs of tenants, Elko said she’d like to know why Atira isn’t “lobbying BC Housing to raise the standard of care here.”

But Abbott said it’s not simply a matter of more funding. Mental health supports are voluntary, and tenants can refuse them. Even when they are being supported by a mental health team, severe mental illness means some tenants will refuse to allow necessary maintenance on their room or refuse treatment for insect infestations.

She said adding too many building staff could mean buildings would start to feel like institutions. Abbott said a better question is whether health, mental health and housing services are working together properly. She said residents can be connected with mental health teams, but still not get all the care they need because it’s not available or because they reject certain interventions.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Atira and many other housing operators limited guests in their buildings — a move that has upset many tenants and that Vancouver Coastal Health warned could be dangerous because it meant more people would use drugs alone, raising the risk of overdosing.

But Abbott said the buildings weren’t designed for the high number of visitors who go through the SROs every day, and she’d like to see an addition to B.C.’s Residential Tenancy Act to “allow some consideration of the number of guests.”

“When you’ve got maybe 10 or 12 or 15 bathrooms for 100 tenants, and then you’ve got 150 people a day coming in, that has a toll on the building, it has a toll on the tenants,” Abbott said.

“So having some kind of special section or accommodation of the uniqueness of single-room occupancy hotels and of supportive housing would be helpful. The trick is always to balance the privacy of the tenant with the reality of supportive housing.” ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Labour + Industry, Housing

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: