Deborah Cook recalls attending family funerals as an adult, and being surprised to bump into friends she’d made at residential school at Port Alberni.

“It would be like, ‘Hey, I'm glad to see you. I haven't seen you since they closed the school down, but why are you here?’” she said. “And they would say, ‘It's because this is my family.’”

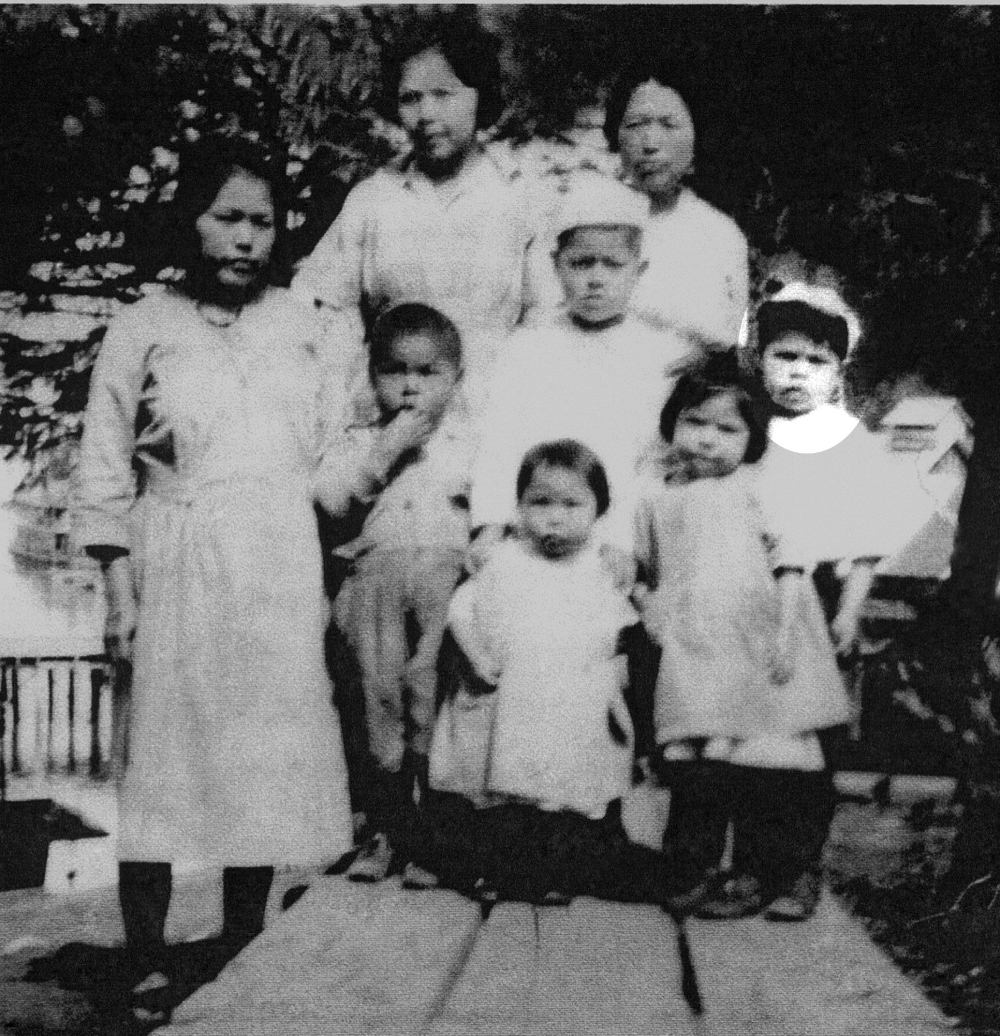

They were more than friends: they were related to her, cousins or sometimes aunts or uncles. Knowledge about their family ties had been taken from them when they were forced to attend residential schools. The colonial institutions separated Indigenous children from their parents and culture for 10 months of the year, provided little education and left students with deep emotional scars from the abuse many endured at the facilities.

The discovery of hundreds of unmarked graves at Indian residential schools this year has also highlighted what was already well-known in First Nations communities: the so-called schools were deadly for Indigenous children.

But the destruction of Indigenous people’s knowledge of their own family relations didn’t start with the residential school system, Cook said. Family relationships were emphasized in Oral Tradition at the beginning of every potlatch, an important ceremony for many B.C. First Nations. Potlatches were banned by the Canadian government between 1885 and 1951 as part of a colonial effort to destroy Indigenous culture.

“At the beginning of every potlatch, they introduce births and deaths within the families. So that you could come away with knowing that part of your history, your family,” said Cook, a member of the Nisga’a Nation who also has ties to the Huu-ay-aht First Nation through marriage.

“But once that was outlawed, and then the children taken to attend residential school, the churches and the government weren't interested in making sure we children know our families. We were never taught that.”

Cook is now using a program developed by the Vancouver Public Library to retrace those lost connections. Participants in the Connection to Kith and Kin program work with librarians and archivists to access the census, death records, military service records and other documentation to build out a complete family tree, sometimes stretching back generations. The program is based out of the VPL’s Britannia branch, although sessions have been taking place over Zoom during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The research process can be more difficult for Indigenous people because racist colonial practices like residential school and the ’60s Scoop disrupted and disconnected families, and can make searching for records harder.

Doing the research can bring up painful emotions, so the program has been designed to include Elders who can support people emotionally and culturally.

“This is a very colonial system, the way all the records were kept, and people could be experiencing trauma just with finding certain records,” said Noreen Ma, the head of the VPL’s Britannia branch and the co-ordinator of the Connection to Kith and Kin program.

“These were written by Indian agents... and there wasn't any sensitivity. If you were Indigenous, then in some of the census sheets, you would be recorded as ‘R’ for ‘red,’ or they might list someone or the ancestor of someone as a ‘savage.’”

Daniel Cook, Deborah’s son, provides technical support for the program, but he also participated in one of the sessions with his mom. Seeing the slapdash way census-takers wrote down information about Indigenous families was a “rage moment” for him, he said. But despite encountering names written incorrectly, he and his mom were still able to use the records to piece together information.

“I got to learn a bit about one ancestor owning a hotel,” Cook said. “I was like, 'Oh that's cool — what happened, where's our hotel right now?'”

Around 75 people have taken part in the program since it began in 2018, Ma said, and some participants have been able to use the information they’ve researched to be able to apply for Indian status (a designation in Canada’s Indian Act) for themselves and other family members. People with Indian status are eligible for benefits like on-reserve housing and extended health benefits.

Participants in the program work at their own pace, with librarians and archivists on hand to help out when people run into research roadblocks. Librarians are able to go beyond the standard genealogical tools like Ancestry.ca, and have sometimes been able to reach out to the churches that ran residential schools and other institutions to get records that might help fill in the gaps.

For Marvin Delorme, participating in the program led to a reunion with family he hadn’t seen in decades. Delorme lives in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood and first heard of the program through a notice on the bulletin board of the nə́c̓aʔmat ct Strathcona library branch. Delorme said he left his home in Grande Cache, Alberta, in 1983 and then spent years lost in alcoholism, moving around the Prairies and B.C. and unable to truly connect with his family.

Delorme has been sober for the past 19 years, but it was participating in the Connection to Kith and Kin program that set him on the path to reconnect with his parents and sisters. When a reporter interviewed him for a story about the program in the Globe and Mail, he sent the article to his sister on Facebook. She reached out, inviting him to come for a visit, and in 2020 he was able to make the trip back to see his parents and sisters.

Delorme said he always thought his entire family was Cree, displaced from the area that became Jasper National Park in 1916. But he learned that some of his ancestors are also Métis, and hailed from places like Quebec and Saskatchewan. Learning about his Métis relations, he suddenly understood why it had been common to hear people speaking Michif as well as Cree when he was growing up.

“I never really could understand why they would speak this foreign language in our community,” Delorme said. “But that’s who we were.”

Cook said she’s now on the hunt for the military service records for her husband’s father, who fought in the Second World War. She said she’s hoping to find out where he did his training, how long he was stationed overseas and where.

Cook is a third-generation residential school survivor: she attended Port Alberni Residential School, her father was sent to Coqualeetza near Chilliwack, and his parents went to Crosby Girls’ and Boys’ Home near Lax Kw’alaams.

“They stole family. They stole my family. I never really feel good about that — besides the fact that they never let me grow up with my own brother and sisters in one house with my parents,” Cook said.

As she’s done more research, more and more names that are familiar to her from residential school have popped up on her family tree. And she’s remembering relatives who would ask her who she was and who her parents were when she came home for the summer, then explain how they were related.

“As a little girl I wouldn't be that interested and say, ‘Oh well hey, you teach me my family tree, I want to know how we’re related,’” Cook said.

“Now that I'm old enough, I want to learn all about it.”

If you are an Indian Residential School survivor, or have been affected by the residential school system and need help, you can contact the 24-hour Indian Residential Schools Crisis Line: 1-866-925-4419. ![]()

Read more: Indigenous, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: