For Elisabeth Ormandy, the turning point came in a laboratory as an undergraduate student at the University of Edinburgh. She was helping to run an experiment with mice that had a gene altered to affect receptors in their brains that mediate learning and memory.

The Morris water maze, named after Ormandy’s professor at the time, neurobiologist Richard Morris, consisted of a circular pool in which the mice were required to find a hidden platform beneath the water. The water was mixed with liquid latex making it opaque in appearance. Since the gene-altered mice could not rely on spatial memory they would swim in circles until they were exhausted and existed in “a perpetual state of anxiety and stress,” recalled Ormandy.

That was 19 years ago. “I remember thinking to myself at the time, to what end are we doing this experiment? Why do I care about spatial recognition in a mouse?” She decided to abandon studying neuroscience and move to the field of animal behaviour and welfare.

Today, Ormandy has a PhD from the University of British Columbia, lives in Vancouver and serves as executive director of the organization she helped establish in 2015, the Canadian Society for Humane Science. The first-of-its-kind Canadian organization is dedicated to promoting non-animal alternatives in teaching, research and testing in Canada.

She joins many other animal rights advocates in watching closely the progress of Bill C-28, unveiled in April by Environment and Climate Change Canada — the first update to the Canadian Environmental Protection Act in two decades.

Ormandy and others say it’s long overdue but that Canada lags behind other nations and needs to do much more.

The CEPA amendment would seek to “reduce, refine or replace the use of” vertebrate-animal testing “when assessing the risks that substances may pose on human health and the environment,” according to a backgrounder on the bill.

In a joint statement, Animal Justice, Humane Canada and the Canadian Society for Humane Science applauded the move as an important first step in ending the painful and often deadly practice of toxicity testing involving tens of thousands of animals each year in Canada.

The tests are outdated, unreliable, unnecessary and ultimately cruel, the three organizations say, and Canada needs to not just lower the use of these tests but to eliminate them as part of a major overhaul of how we treat animals in this country.

A more ambitious try was made with Bill S-214, which passed the Senate in 2018, but died on the order paper in the House of Commons when the 2019 federal election was called.

That bill, introduced by Conservative Sen. Carolyn Stewart-Olsen, would have amended the Food and Drugs Act to prohibit cosmetic animal testing and the sale of cosmetics developed or manufactured using cosmetic animal testing.

The animal-testing provision in the revised CEPA is a good starting point, according to Camille Labchuk, a lawyer and executive director of Animal Justice, Canada’s only national animal law advocacy organization, based in Toronto.

Labchuck believes the amendment will help Canada catch up with the European Union and the United States, both of which have strengthened their laws to require non-animal toxicity-testing methods be developed and adopted.

In a 2019 memorandum, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency also committed to “reducing its requests for, and funding of, mammal studies by 30 per cent by 2025.” Toxicity testing on animals would end by 2035.

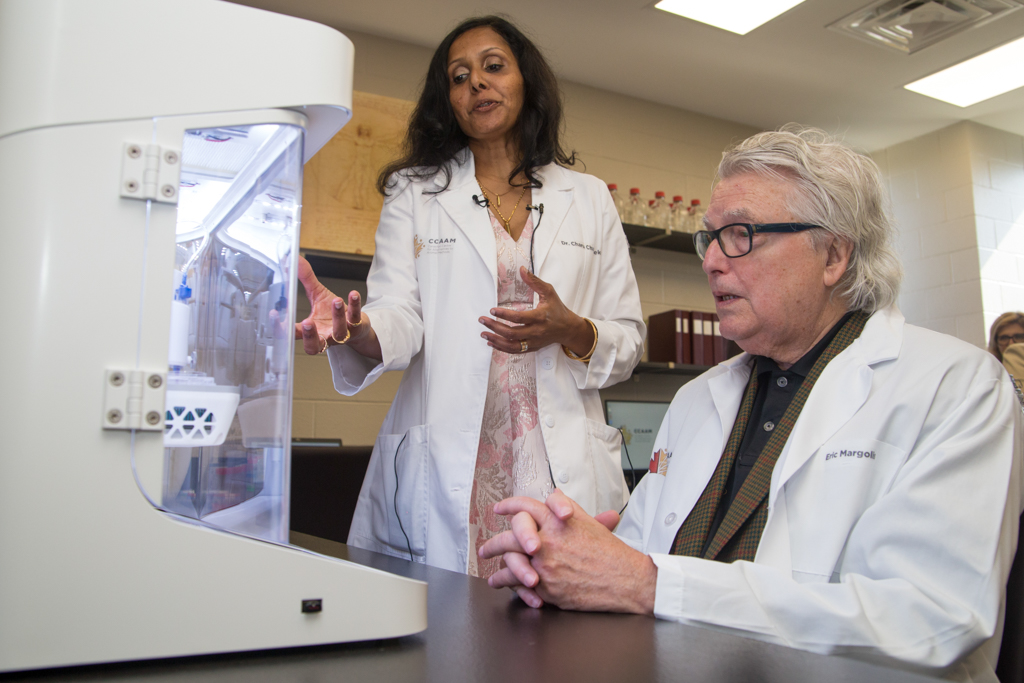

Labchuk said that the U.S. and the EU both invest dollars into alternative-research methods but Canada does not — despite having a world-class facility dedicated to that very goal at the University of Windsor.

UW’s Canadian Centre for Alternatives to Animal Methods explains in its mission statement: “Experimental animals continue to serve as the gold standard in biomedical research [but] 95 per cent of drugs tested to be safe and effective in animals fail in human clinical trials. Similarly, for evaluating the safety of chemicals, the legacy animal-based methods are not sufficiently reliable to accurately predict adverse outcomes on human health and the environment.”

The testing hub, which is designing such non-animal methods as cultured tissues, computer modelling and organs-on-a-chip, receives no funding from the federal government, and Labchuk and others want that to change.

Currently in Canada, animals are used to test the safety — for humans — of a range of consumer products, including cosmetics, cleaners and pesticides.

“These tests are often some of the most harmful and painful ways that we use animals in scientific research, because the point is to see at what level these products are toxic on animals and try to make conclusions on how they might affect humans,” said Labchuk.

For instance, in the Draize test, devised by toxicologists at the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 1944, cosmetics are inserted into the eyes or onto the skin of restrained rabbits to measure the effects of the substance, which can lead to blindness or edema. Humane Society International recently released a short film advocating for a global ban on cosmetic testing on animals.

An animal testing regulator without teeth

Grisly experimentation on animals has been the subject of video exposés by animal rights advocates and news media, in which CTV’s W5 featured disturbing undercover footage at a Montreal animal research lab, exposing mistreatment of hundreds of dogs, pigs and monkeys.

In 2019, 4,562,522 animals were involved in Canadian research, testing and education, according to the Canadian Council on Animal Care, an Ottawa-based non-profit peer-review organization that gathers data from about 200 academic as well as public and private-sector organizations it certifies.

The population of animals involved in testing and research is rising, according to an analysis of the CCAC’s 2019 data by the Society for Humane Science, which found that nearly 100,000 of the experimental animals are exposed to the highest category of inflicted pain (see sidebar).

In a statement sent to The Tyee, Environment and Climate Change Canada spokesperson Krystyna Dodds said that the animal-testing reference in the CEPA preamble “will recognize the importance of promoting new alternative methods and strategies in the testing and assessment of substances to move away from over-reliance on animal testing (particularly vertebrate animals) and towards computational models and other new approach methodologies.” This, she said, would align with similar commitments codified in U.S. and European Union laws.

CCAC executive director Pierre Verreault told The Tyee his organization “welcomes” the proposed CEPA provision, and believes the federal government should go further in adding milestones like the U.S. has set to discontinue toxicity testing on animals.

A 2018 survey commissioned by CCAC found that more than three in four Canadians found it acceptable to use animals to test medicines, but more than 90 per cent of the 1,000 respondents said the “welfare of the animals being tested is important or somewhat important when deciding whether to include an animal in a study.”

Verreault explained that the CCAC takes no position “for or against the use of animals in Canadian science.”

“Our role is that when it happens — if it has scientific merit; if it has pedagogical merit; and if it is regulatory testing — we make sure that it happens in an ethical way for the best care possible for the animals.”

For instance, the abuse revealed in W5’s 2017 exposé of Montreal-based International Toxicology Research Laboratories Canada, which remains certified by the CCAC, was addressed and resolved, said Verreault.

ITR “had to change many things, but brought it back to standards," he said, but declined to provide any details.

“Some of the images you saw [on W5] of the rough handling of animals were hard to look at — and there is never any need for that.”

Verreault added that the CCAC’s ethical principles are being reviewed and updated.

Environment and Climate Change’s Dodds said Canadian scientists are part of a global network working to develop non-animal methods of testing.

But alternative methods are already being used elsewhere. France’s L’Oréal now only conducts safety tests on its cosmetics using human stem-cells through its tissue-engineering subsidiary, Episkin. Other cosmetic brands have also banned animal testing.

Verreault expects that when sound alternatives are available in Canada, animals will no longer be poked, prodded or worse in the name of science. “But it will be a gradual process,” he offered, adding that using animals in labs is expensive.

However, Labchuk said there is no federal law that governs the type of scientific procedures that can be performed on animals or which provides for government inspections of research labs.

She explained that instead of Ottawa establishing a regulatory body, the National Research Council created the CCAC in 1968, with funding from both the government and CAC-certified institutions participating in its programs.

“But it has no law-enforcement authority,” said Labchuk.

Verreault said the CCAC has standards that certified institutions must follow for research, teaching and regulatory testing. The council has withdrawn a certification license in the past, and in 2019, six institutions were placed on a one-year probation — but the reasons for the actions are confidential, said Verreault.

Ormandy, who was a research fellow in animal policy development for CCAC from 2009 to 2011, explained the process to obtain approval from the council to use animals for research.

The application goes to one of about 200 local animal care committees across the country, whose membership includes veterinarians, animal-welfare experts, researchers, bioethicists and members of the public.

Ormandy said that, “the majority of people on those committees are scientists who have an investment in animal research continuing, so rejections happen very rarely.”

Private labs unaffiliated with CCAC can essentially conduct whatever animal research they like.

“The only way you would ever get any inspection of those private facilities is if there was a whistleblower who reported it under provincial cruelty-to-animals legislation,” she explained.

Canada lags UK and US on lab animal protections

Ormandy noted that the United Kingdom is miles ahead of Canada on this file. There, scientists wishing to use animals in research must receive approval at three levels. The researcher must first obtain a personal license and then one for the project, outlining the scope of the research. The researcher must also receive a government-issued certificate that designates where the regulated procedures will be conducted.

“You are also subject to random and routine visits by a home office inspector,” explained Ormandy, who shadowed one of those inspectors in her research fellowship with the CCAC. “In Canada, there are no unannounced visits.”

With its Animals for Research Act, Ontario is the only Canadian jurisdiction with regulations that “enables an inspectorate to control the registration of research facilities” and issue licenses for them, according to the CCAC.

However, Ormandy contended that Canadian laws “only really protect animals from the most egregious and wanton cruelty, whether that’s under the Criminal Code or provincial laws.”

“Canada has no Animal Welfare Act that lays out suitable conditions for animals on farms or in labs or in zoos or in aquariums.”

Labchuk, who served as press secretary to former federal Green party leader Elizabeth May from 2006 to 2008, agreed that Canada has been slow to reform animal protection, calling its research protections “a joke” compared to other countries.

She said the U.S. Animal Welfare Act features a national regulatory scheme with U.S. Department of Agriculture inspections and reports that are made public.

Liberal MP Nathaniel Erskine-Smith, who represents the Toronto riding of Beaches-East York, would like Canada to follow the U.S. milestones to eliminate animals in research labs — and have the federal government lead a campaign to encourage the country’s scientific community to begin finding non-animal alternatives for their research.

“The U.S. has proper targets to phase out animal testing in the same way we set a goal to reduce our carbon emissions by 2030 and reach net-zero by 2050 to address climate change,” said Erskine-Smith, who holds a master’s degree in law from the University of Oxford, where he studied constitutional law.

After winning election in 2015, the first private member’s bill Erskine-Smith introduced in the House of Commons was C-246. Also known as the Modernizing Animal Protections Act, the bill was tabled in early 2016 but was defeated at second reading; 117 Liberal MPs, including Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, voted against it. Only 39 Liberals voted for it.

Had Erskine-Smith’s bill passed, it would have given Canada’s animal-welfare legislation its first update since 1892 when animal-cruelty offences were added to the Criminal Code.

Erskine-Smith’s bill would have strengthened criminal penalties against those who kill, or cause unnecessary pain, suffering or injury to an animal, and added the new offence of gross negligence.

Some of the provisions would later end up in law, such as a ban on both animal fighting and importing shark fins.

And Erskine-Smith hasn’t given up pressing for change. He is part of a movement to improve animal welfare in Canada not only in the nation’s laboratories, but for our farms and food processing factories — and write those reforms into law.

More on that in the second part of this series, which runs tomorrow. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Science + Tech

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: