Lilia Zaharieva lived in COVID-like conditions long before the pandemic. Like the 4,300 other Canadians with cystic fibrosis, she has an impaired immune response. The illness has forced her to spend much of her life practising physical distancing or staying home alone.

But those safety measures didn’t stop the progression of the disease through her body. In recent years, her average lung function has hovered around 30 per cent. It’s been a constant struggle just to breathe.

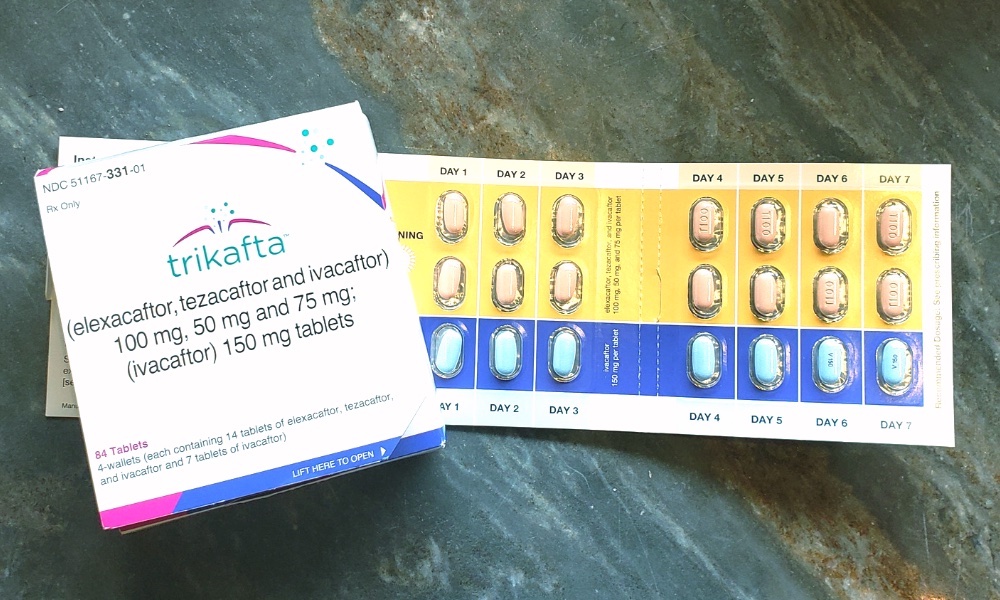

The good news for Zaharieva is that she is now taking a new drug called Trikafta that has significantly expanded her lung capacity. “For the first time in my whole life, I’m feeling really good. It feels like science fiction.”

But Zaharieva’s story is also one of ongoing struggle and doubt, because Trikafta carries a huge price tag and in Canada is still in its experimental phase. Zaharieva is caught up in a tangle of realities posed by the arrival of potential “breakthrough” drugs like this one.

Trikafta is only accessible through the benevolence of a corporation. How its six-figure price is set is hidden behind an opaque negotiation between its maker and federal officials. And Canada’s governments only cover such drugs once it’s decided they are “cost-effective” — even if they can be life-saving for some people with rare diseases.

Which means Zaharieva, and many others in drug trials, must carry the nagging fear the medicine that has transformed their lives might be cancelled or denied coverage, pricing it beyond their means.

And so Zaharieva has directed a lot of her limited energy into fighting the government for her very survival.

‘I felt the difference within hours’

There is no cure for cystic fibrosis, the most fatal genetic disease affecting children and young adults in Canada. Zaharieva was diagnosed at age two and told at a young age that she wouldn’t live to see 32. After turning 25, she stopped celebrating her birthday altogether.

“In a sense, cystic fibrosis always gives you that feeling of time ticking down,” she said. “I’ve lived my whole life basically between hospital visits.”

For years, she has fought for governments to pay for the drugs she needs to fight against the progression of her disease — cystic fibrosis primarily targets the lungs and digestive system but can also cause diabetes, malnutrition and male infertility.

Then came Trikafta. Researchers say the drug allows them to treat the underlying genetic defect that causes cystic fibrosis for the first time. The drug has the potential to help 90 per cent of those diagnosed with the disease.

Trikafta is not currently authorized for sale in Canada but was approved at the end of 2020 for an expedited drug review process. About 165 Canadians, including Zaharieva, already access the drug for free on a compassionate basis from Vertex Pharmaceuticals, the drug manufacturer, due to the severity of their condition.

“I felt the difference within the first few hours, and within four days, I didn’t recognize my own body,” said Zaharieva, who started her first dose of Trikafta in May 2020.

A 2020 study from Dalhousie University projects that if Trikafta was made available to Canadians in 2021, it could lead to dramatic improvements in the conditions of those with cystic fibrosis over the next decade. Forecasts show Trikafta reducing deaths by 15 per cent, as well as reducing severe lung disease by 60 per cent.

“In an individual, it has really profound effects in terms of improving your lung function and reducing the need for hospitalizations,” said Sanja Stanojevic, assistant professor in the department of community health and epidemiology at Dalhousie University and lead author on the study.

“We certainly didn’t anticipate the nearly 10-year improvement in survival, over the next 15 years, and we didn’t anticipate such a strong reduction in those people with severe disease.”

The Canadian Drug Expert Committee will decide whether to recommend Trikafta for approval on June 16, and Health Canada will make the final decision on June 23.

“We’ve been waiting so long for this day,” said Chris Black, volunteer lead provincial advocate for Cystic Fibrosis Canada. “We just need it to happen quickly, so we’re asking our minister of health to commit to providing access to Trikafta, as soon as possible.”

There are more than 1,700 known mutations of cystic fibrosis, so the experiences of those on drugs like Trikafta can be diverse.

“I can breathe again in ways that I’ve never been able to breathe and do things that I haven’t been able to do since I was 14 or 15,” said Matt Emig, who has been on Trikafta since mid-March.

Five years ago, Emig found that he couldn’t go hiking in the mountains anymore. Since starting Trikafta, he’s been out surfing the waves by his home in Tofino twice a week and once again can hike and bike. Cystic fibrosis often causes sinus infections, which caused Emig to lose much of his senses of taste and smell — something that has come back in recent weeks, to his amazement.

Emig says the coughing that used to keep him up every night, leaving him frequently with three hours of sleep, has disappeared. He’s now getting a full night’s sleep.

Trina Atchison was part of the first phase of the Canadian drug study for Trikafta in October 2018. Although it was a double-blind study, she says she quickly realized that she wasn’t receiving a placebo.

At her first pulmonary function test, two weeks into the six-month study, she and the researcher started crying from joy. Her results, usually in the 60s, came back at 87 per cent. Prior to starting the drug, Atchison says, she had been hospitalized for four months.

“Trikafta healed the holes in my lungs,” she said. “There are scans of my lungs, and you can see the holes in them, and then there are scans six months later and the holes are gone. It’s insane.”

The case for caution

Trikafta was approved by the United States in 2019, and in the United Kingdom and Australia in 2020. At least 18 countries have greenlit the drug.

However, there are dangers with taking unapproved medicines outside of a clinical trial, warned Alan Cassels, a drug policy researcher at the University of Victoria. Even after approval, he says, there can be dangers with drugs that have yet to be tested on larger populations.

“We’ve seen instances where drugs get approved really quickly and introduced to the market, and then we discovered the harms involved after exposing them to thousands of patients,” Cassels said.

Those who have received compassionate coverage of Trikafta from Vertex express feelings of survivor’s guilt for others who are not yet able to access the drug in Canada, or who may never gain access to it due to the anticipated high cost of the drug.

“Canada is praised for its health-care system, but it’s so incredibly flawed, especially when it comes to getting access to life-saving medications and different therapies and things like that for people with rare diseases,” Atchison says.

Secret pricing negotiations

Canada has yet to set a price for Trikafta, which will be negotiated once the drug is approved. In the United States, it costs US$311,000 per year.

Drug price negotiations between pharmaceutical companies and the federal government are confidential.

Cassels is critical of the secretive processes around the regulation of these prices — particularly as Canada has the third-highest drug prices in the world. Vertex has also been accused by advocates of leveraging its monopoly on cystic fibrosis treatments in drug price negotiations.

Vertex declined to comment on these claims, compassionate coverage or the factors that go into their decision to set the prices of certain drugs like Trikafta, saying that it is currently in negotiations with the pan-Canadian Pharmaceutical Alliance.

“I feel that sometimes, patients are being held hostage,” said Cassels. Patients struggle so that they can afford drugs not covered by the government because they are told of the potentially life-saving benefits, which he feels may not always be true.

For example, the drug Orkambi, which also treats cystic fibrosis, was found to result in a “modest improvement in lung function” in B.C. government trials. But some who took the $250,000-a-year drug found that it didn’t work nearly as well as hoped, including several of the people interviewed for this story.

And even for cystic fibrosis patients who receive coverage of their drugs, and for whom the drugs make a difference in their lives and stability, long-term security isn’t always assured.

Deciding to fight

When Zaharieva’s health-care provider at the University of Victoria abruptly informed her in 2017 that her coverage of Orkambi was ending, she found herself with only eight days left of the little pink pills. Without coverage, she knew she was facing a quick, painful decline in her health.

Her first thought was to sell everything she owned to afford the medicine — but as a friend reminded her, she didn’t own much and would soon be left with nothing.

So Zaharieva decided to fight. She launched a public campaign for British Columbia to provide Orkambi coverage. The next few months were a whirlwind of rallies, meetings with Members of the Legislative Assembly and media interviews as her fight for coverage garnered national attention.

But the battle took its toll. Zaharieva said an elected representative told her that by advocating for the B.C. government to cover an expensive therapy, she was “taking money from families and children.”

She was horrified to see the value of Orkambi, of her existence, constantly debated in the news. “I felt so dehumanized having a price on my life,” she said.

In 2017, B.C. decided it was “not cost-effective” to cover Orkambi due to the steep price and because the benefits “were of uncertain clinical significance.”

Instead, Zaharieva was able to stay on Orkambi through support from the community. The University of Victoria Student Society paid for a month’s supply, and members of the community raised funds as she began to ration her doses. Eventually in 2018, she was offered compassionate coverage by Vertex.

“I didn’t miss a day, which was incredible,” she says. “So many people were not that lucky.”

As many others are still unable to access Orkambi, Zaharieva joined another cystic fibrosis patient and advocate Melissa Verleg as a lead co-plaintiff to launch a class action lawsuit against the B.C. government for denying coverage to them and others with cystic fibrosis.

The case was delayed later in 2018 due to health complications faced by Zaharieva and Verleg, the latter of whom ended up in the ICU after losing access to Orkambi. However, Zaharieva has expressed interest in continuing to pursue the case following the release of the 2020 UN report on ableism.

When she first found out about the potential to switch to Trikafta from Orkambi, she didn’t even want to ask out of fear she would lose compassionate coverage.

‘Reverse grief’

Once Zaharieva was placed on Trikafta, she said she experienced a feeling she describes as “reverse grief.”

“At first, I couldn't believe what was happening,” she said. “And then I was so anxious to lose the medicine. So I was just sobbing all the time, everything made me cry.”

Knowing there are others out there who aren’t lucky enough to receive coverage of medications that could improve their quality of life, much like herself in 2017, is something that breaks Zaharieva’s heart.

“When I think of those who are waiting for this drug, I feel pain in every cell of my body,” she said. “Everyone has a taste of wanting to emerge from isolation, fear and a sense of foreshortened future for a drug.”

Atchison believes Trikafta could help prevent young cystic fibrosis patients, especially children, from developing irreversible scar tissue and damage from the disease. Instead of a life sentence, the disease may one day be manageable.

“It’s not a cure, but it’s an incredibly good treatment for 90 per cent of patients,” said Abby McFee, who has been on Trikafta since May 2020. “I think it’s going to be a real game changer.”

McFee is also optimistic for the precedent Trikafta could set in hastening the long approval process for rare disease drugs.

“I see this kind of laying a foundation to opening a pathway for rare disease drugs to get approved much quicker than they currently are,” she said.

Zaharieva sees a lesson in how quickly COVID-19 vaccines were produced and distributed, whatever the cost. “‘Big Pharma’ gets a major rebrand when able-bodied people live one year of inconvenience,” she said.

On Feb. 25, Zaharieva celebrated her 34th birthday — a milestone the doctors had doubted she’d reach. Trikafta, she reflects, “not only saved my life from end stage, but made me better within four days. I’m just so lucky to be the recipient of 20 years of research.”

On a walk one night in late summer, a few months into starting Trikafta, she found herself at the bottom of Sinclair Road in Victoria. The hill before her was steep. A year before, she would have had to take two breaks to walk up it. Zaharieva started to sprint.

Suddenly, she was at the top. She ran back down and did it again. And again. After the sixth time she collapsed onto the darkened street, crying with joy at the ability to run.

“It feels exhilarating. Like when you’re a little kid.” ![]()

Read more: Health, Rights + Justice

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: