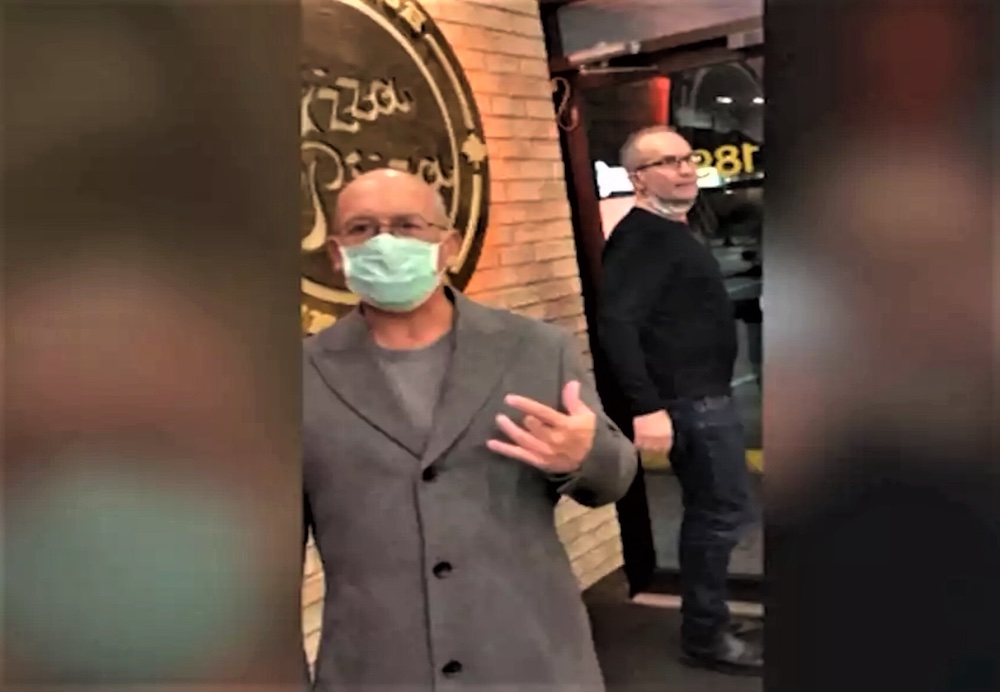

In the final hour of Feb. 20, two smartly dressed, middle-aged white guys cruising around Vancouver decided they had a hankering for pizza. The stakes seemed pretty low when they pulled into Pizza Pizza, a glowing outpost in an otherwise dimly lit plaza on the eastern edge of the Kitsilano neighbourhood.

But within a few minutes a video camera had captured the men screaming bigoted insults at the young workers and boasting of their riches compared to the servers “worth zero.”

On their way out of the store, a recording shows, the men encountered an apparently Asian teenager and physically attacked him.

The incident made the news and soon it was announced that Brenton Woyat, a wealth manager, and James Davidson, whose line of work remains unknown, had been charged with assault, and one with impaired driving.

What seemed to trigger their meltdown was the simple request by the staff that if the two customers wanted to come inside their place of work, they wear masks. The men were even offered a free one.

Such compliance, prescribed by the province’s top doctor, is expected of anyone entering public establishments in order to slow the spreading of COVID-19 infection a year into the pandemic, which has claimed 1,397 lives in B.C. and 22,428 in Canada. Put on this mask, here’s your pizza, have a good night. Simple enough.

Which makes the whole conflagration a weird one-off — or does it?

Experts The Tyee talked to say versions of the bizarre episode are all too common during the pandemic. They can be distillations of toxic masculinity, a sense of entitlement or superiority, contempt for low-wage workers, xenophobia and racism — released after being whipped up by far-right rhetoric, social media algorithms, and liquor or drugs.

In fact, the Pizza Pizza incident joins a number of documented attacks on retail and service employees by British Columbians incensed by the face mask requirement.

Staff at a camera shop in the upscale Kerrisdale neighbourhood endured a customer proclaiming to them: “What’s amazing is the level of brainwashing the vast majority of the public are under.” And, “This is discrimination.”

In Dawson Creek, a Walmart customer refusing to wear a mask pummeled a store greeter to the ground, repeatedly punching his head into the floor.*

In Nelson, a hotel employee suffered a heart attack after being spat on and screamed at by a customer refusing to wear a mask.

That night at Pizza Pizza, Woyat stood at the counter wearing a mask. But Davidson clutched one in his hand or wore it uselessly under his chin, his mouth exposed as he declared, “You're Nazis. You guys are complete fucking morons. COVID is a joke. You guys are fucking brainwashed.”

He shouted: “Are you fucking Middle Eastern or where are you from?” And, “I’m worth $50 million, you’re worth zero.”

Dr. Steven Taylor, a psychologist in the University of British Columbia’s psychiatry department and author of the book The Psychology of Pandemics, said he couldn’t comment specifically on the men charged in any particular incident without assessing them directly. But he noted there is a psychological pattern to many of the mask-related confrontations during the past year. It can be a backlash by people outraged by the feeling that people beneath them are giving them orders.

“You get these dramatic blow-ups that are displayed when people are told what to do and it threatens their sense of entitlement,” Taylor said. “And if you’re not only being told what to do, but being told what to do by someone perceived as being at a lower-status level, it escalates a sense of unfairness for a person with a strong sense of entitlement.”

At the receiving end of such abuse are often the lowest-paid, frontline workers, expected to enforce public health orders “in a highly individualistic society where there’s an allergic reaction to being told what to do.”

Woyat has been suspended from his job at Canaccord Genuity pending a company investigation. “We are incredibly disappointed to learn of a shameful incident of inexcusable behaviour involving one of our employees,” the company said in a statement. The Tyee’s attempts to reach Woyat were unsuccessful.

A person matching Davidson’s name was sued a year ago by a woman sharing his last name in a family law proceeding over a motor vehicle accident, the case settled.

Reached by The Tyee, Davidson said, “There was no racial motivation whatsoever. The only thing this whole story was related to was a huge excess of alcohol. No other story here. I am very saddened by the event but cannot comment further.”

He told reporter Bob Mackin “it’s drunk and disorderly; basically there’s no mask connotations, we have no feelings about that.”

For many people, alcohol has a “disinhibitory influence” that can lead to them expressing ugly views, noted Taylor. But the COVID-19 crisis has produced other influences as well. “Pandemics are pressure cookers that exacerbate social extremes,” Taylor said.

While this pandemic, like others in history, has supercharged racism and xenophobia, what’s very up-to-date about this one are new kinds of disinhibitory influences, experts note.

The pandemic is filtered through the internet and a media sphere that provides ready access to right-wingers railing against the government, and conspiracy theorists promoting the myth that public health measures are part of an oppressive hoax.

And some of those influences are racists. “Is everyone who’s a COVID-conspiracist also a racist? No,” said Evan Balgord, executive director of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, in an interview. “But we’re seeing this unfortunately mainstream COVID conspiracy anti-lockdown movement managing to attract far-right individuals. Every hate group we monitor is somehow involved in COVID conspiracies.”

Connections are formed on the web as a pandemic skeptic searches for information and like-minded thinkers, he said. “What I’ll call ‘regular’ conspiracy theorists might not immediately recognize they’re talking to a neo-Nazi online, but what starts as a Venn diagram becomes closer to a circle.”

The effect is heightened by social media algorithms that sense a user’s interests and then target them with select content and advertisements that expose them to concentrated, more-extreme versions of their views and sympathies. Facebook and Twitter have said they’re cracking down on extremism. “But it hasn’t really worked yet,” Balgord said.

Vancouver Police Department spokesperson Sgt. Steve Addison told The Tyee that at Pizza Pizza, “both men allegedly became verbally aggressive, swearing and making racial slurs at staff” and that “those details will make up evidence that will be part of a court case.”

BC Community Alliance organizer Markiel Simpson asks: “What was the motivating factor for those two men to go out and assault that random Asian person, when we’ve had a more than 700-per-cent spike in random acts of violence against Asians in the city? To me, it appears that might have been motivated racially.”

He is troubled the perpetrators so far are not charged with hate crimes. A weakness in Canada’s hate crimes law, he says, means judges only consider racist motivations at time of sentencing.

“I feel the police aren’t connecting those dots,” Simpson said. “You’d think that type of incident from the Pizza Pizza meets the threshold” for a hate crime charge. “Or it should.”

For low-wage workers — disproportionately people of colour — such attacks by customers are “not just demoralizing,” said Simpson, “but for groups of people who aren’t reflected in positions of power, it comes with sentiments of disenfranchisement.”

When Balgord looks at the Pizza Pizza incident and similar ones, he concludes it’s not those struggling the hardest financially who are most likely to lash out against wearing a mask or other health measures related to the pandemic.

“It’s not about economic anxieties,” Balgord said. “Are there people who are severely economically damaged by what’s happened through COVID? Yes. But many come from means, who are doing better than okay.”

Divisions related to the pandemic were chronicled last week in a Research Co. opinion poll that found nearly one in every five British Columbians think the coronavirus pandemic is definitely or probably “not a real threat,” or weren’t sure. Pandemic skeptics were most likely to mistrust the media’s pandemic coverage and governments’ response.

Nearly one in six polled said that because of a disagreement related to COVID-19, they have unfollowed a person on social media, while 13 per cent ceased communication with a friend and eight per cent have stopped talking to a family member.

People who did not consider COVID a threat reported a much higher degree of alienation from friends and family over the issue.

The largest group in B.C. who are certain COVID-19 is not a “real threat” were aged 35 to 54.

It’s two young people of colour, as usual, behind the counter of Pizza Pizza at 11:30 on a Saturday night two weeks after the eatery became a briefly famous example of how pandemic pressures trigger abuse and violence. The employees who were on duty then aren’t working this evening. Tonight’s pair hustle efficiently to ready pizzas and cheesy bread for customers as an Uber Eats driver waits and a manager takes calls in the back.

The employees prefer not to talk to a reporter and they demur when asked to bring out their boss for a try at an interview. At the same strip mall, the Starbucks and Triple O’s are dark, and despite a sign boasting “Open 24 hours,” Siegel’s Bagels is locked, lit only by a flickering fire tended by overnight bakers. Across the street, Lululemon’s red logo peers like an eye from the blackness.

In such settings, frontline retail workers need protections and supports while doing their job, in the view of UBC psychologist Taylor. “If you’re at Pizza Pizza or Subway and getting abused by clients, you need strong management and a sense they’re there to support them, to debrief with them.”

To endure such attacks has “got to be really stressful and they’re going to need the same sorts of supports as for health-care workers. Workplaces need to be proactive and prepared.”

Every person reacts differently in the aftermath. But if a conflict causes them to feel “stuck,” ruminating about what happened long afterwards, it’s important they reach out for help — and inquire if there are any employee assistance supports from their employer.

“It might be a good idea to talk it over with friends or family, your family doctor, or seek the advice of a mental health professional,” Taylor said. Discuss it with “anyone who can acknowledge the outrageousness and inappropriateness of what happened to you. The situation was not your fault, but others can help you cope with the injustice of it.”

There is something valuable to learn, as well, for people who feel the urge to explode when asked to put on a mask by a person just doing their job.

The Pizza Pizza incident is an example of what Taylor called “maladaptive behaviours,” which is to say self-defeating actions that harm the person doing them.

“They create the very problems they’re intended to solve,” he explained. “Blowing up in a pizza parlour is self-defeating. You get arrested and spend the night in jail. You get fined. You have to deal with the conflict you’ve created.

“And in the end, you don’t even get your pizza.”

*Story updated on April 28 at 11:39 a.m. to correct the B.C. community where a store greeter was attacked after telling a customer to wear a mask. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Coronavirus, Media

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: