The Canadian history taught in schools today is not the same education that Samantha Cutrara received over 20 years ago.

“There’s a real trend right now on historical thinking, on teaching the historical method and teaching with primary sources,” said Cutrara, a history education strategist. “There is more of an emphasis on inquiry in classrooms.”

There’s more Indigenous content today, too, thanks in large part to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s 2015 Calls to Action that demanded schools teach the whole history of settler-Indigenous relations. And there’s more consideration given to the histories of Black and people of colour, particularly around Black History Month in February.

But the focus of Canadian history education is still on white, male, heterosexual, European-descendent Canadian settlers, says Cutrara, to the near-exclusion of Indigenous, Black, people of colour, immigrants, women, queer and trans people.

What does exist in terms of diverse histories, Cutrara says, is typically included without context — what she calls “add and stir” additions to the curriculum.

As a PhD student in 2011, Cutrara observed four Canadian history classes in Ontario, speaking to high school students who “hated” Canadian history, many of whom were people of colour, Indigenous or Black.

Because of the white heterogeneous focus, the curriculum failed to engage students, Cutrara said, let alone encourage efforts to present a history that challenged colonialism, racism, sexism or homophobia.

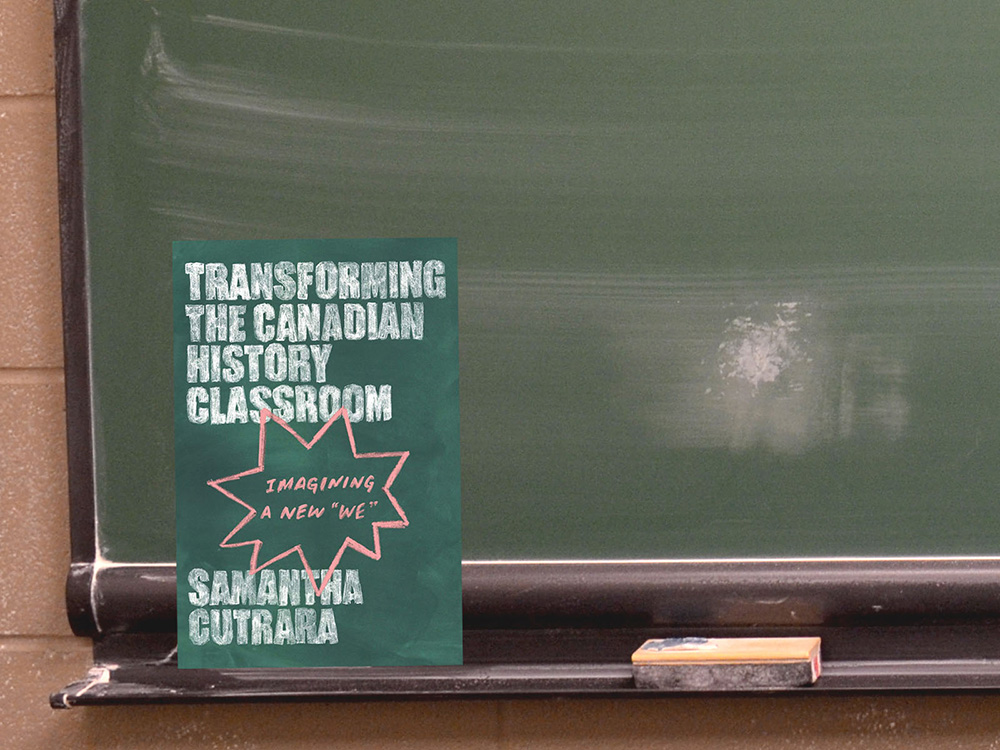

With her new book, Transforming the Canadian History Classroom: Imagining a New “We,” published by UBC Press, Cutrara aims to change how Canadian history is taught, arguing we can turn the topic from “ho hum” to engaging for all students.

The Tyee spoke with Cutrara about her path to becoming an advocate for a transformed history education, her theory of “Historic Space,” and her hope the book will reach everyone dissatisfied with their Canadian history education. The interview has been lightly edited for clarity and length.

The Tyee: What inspired you to get into Canadian history education?

Samantha Cutrara: I was doing an undergrad degree in transnational women’s studies and I also worked at a “pioneer” museum where I was in a full costume. I could see that I could bring some of these theories of intersectional feminist analysis into this very traditional space. Not only that, I could see that it was really needed to push beyond boundaries of gender, but also how we understood things like ethnicity and the past.

From that experience, I developed something called “Historic Space,” the idea that we understand history in these little compact spaces, and we need to challenge those spaces. That is the work I’ve been doing since then, through my graduate education and my professional work.

How are you proposing we change how Canadian history is taught?

When I say “we,” I mean anyone that’s doing any sort of education. We really need to think about who and what we consider to be Canadian. Because what I talk about a lot in the book is that a teacher often will look at racialized students, look at students that are different from him or her and say, “I’m the real Canadian; those students aren’t. It’s my responsibility to teach them Canadian history.” And what I argue in the book, which is why the subtitle is Imagining a New ‘We,’ is that we need to have a broader, inclusive understanding about who and what is on this land and how that influences how we are Canadian and how we understand the Canadian past.

The second thing is I think we need to [do] — again, this comes back to Historic Space — is yes, make sure that traditional history is taught, but bring in counter-stories as a way to challenge that traditional narrative. Because if we’re not challenging that traditional narrative through the stories we tell and the questions we ask, we wind up doing “add and stir.” And that’s certainly something we want to move away from.

A lot of the book is about getting young people to bring their own histories and teach the class, is that right?

Yes. Bringing in their own histories, but also bringing in the questions that young people fundamentally have about who they are in the world around them. So it’s not just about bringing in histories that match a student’s identity. It’s bringing in the complexities of all of our lives and acknowledging those complexities. And when we do that, it is easier for students to see themselves within history.

There are a lot of classrooms in Canada that are entirely white. What kind of complexities would you bring in when everyone seemingly has the same racial background?

It’s not just complexities of race. It’s also complexities of identity, migration, class, gender, sexuality, family home-life composition. There are so many ways that we can understand the complexities of our lives. So if there’s a whole class full of students who are white, there are probably a lot of things that are dissimilar about them as well. Maybe they are interested in travelling, maybe they have a history of migration, maybe they have different relationships with labour, gender, sexuality, all these areas. Just because there’s a class full of white students doesn’t mean they’re still not trying to figure out who they are in this world.

And in particular, for students who might be leaning towards white supremacist feelings because they feel really threatened by things like Black Lives Matter, helping them understand the complexities of whiteness might be able to dispel some of that anger and fear that comes from those types of actions and beliefs.

How diverse were the educators you spoke to?

The teachers that I worked with in the research all identified as heterosexual white women. They were different ages and in the teaching profession for different amounts of time. There wasn’t actually a lot of diversity in the teaching faculty I worked with, which makes sense. The majority of teachers are white women.

Most of the teachers I’ve spoken to really have a desire to teach towards students they see are marginalized. And white teachers, myself included, can often fall into this trap of being a “good” white by just acknowledging whiteness or acknowledging racial inequity.

What I say in the book is even though you think that might be enough, that is actually the worst thing you can do, because you’re not going far enough. I’ve seen that teachers are willing to do this work, but often they just don’t have the kind of critical tools to do it in the ways that align with who their students are and what they need.

My work is based in critical race theory, in intersectional feminist theory. And a lot of the work that I draw on is from mainly racialized women scholars who are writing about dynamics of race, and teaching and whiteness, in ways that really helped me understand more of the dynamics that I was seeing in the classroom.

The history education theory community in Canada is very white. And when you are going to these spaces to present with other academics, they all agree with you, but we’re all coming from similar racial backgrounds. And so, what I often do is also go to conferences, or I watch talks, or I work with other scholars who are mainly doing Black history, not history education, but Black history. Because then you can see the types of storytelling that are happening outside the history education community.

That is something that I think those of us in the history education community need to reconcile more. Why is the history education community so white, but there are so many other scholars doing work on histories related to different First Nations, Black Canadians, Jewish Canadians, Asian Canadians? In the book, I try to build on some of those theories and bring them together.

How would you scale up the practice of teaching a more critical history education?

Scaling up to me suggests a bigger approach. What I think teachers need to do is try to do less. Don’t think that they need to know everything and allow the classroom to be a space of community, collaboration, exploration, inquiry. Teachers don’t need to feel like “I need to know all these histories,” but rather, to enter a classroom being like, “Let’s look these things up together.” And I think that is a way we can get to a “more authentic” history education that allows for greater complexities.

When teachers put that burden all on themselves, they’re inevitably going to fail, because we’re just humans. We’re not going to be able to know everything. It’s allowing for greater space to be in community with the people in your classrooms and the people in your community.

Should we be changing, though, how we teach people to become teachers?

Certainly. There’s a lot of people who do really excellent work in faculties of education trying to get teacher candidates to do different things. But research has also shown that teachers approach their work with a purpose defined before becoming a teacher. So a lot of that stuff they learned that might be different than how they were taught history doesn’t necessarily get through.

I think that helping teachers articulate their purpose and to know they don’t need to know everything, those are the keys that are going to help them be able to build those communities in their classroom.

We can have tools and tricks and methods, but at the end of the day, it’s about relationships and how we’re going to centre that in the classroom.

What would you say to people who say this way of teaching history is politically correct or too political for schools?

It’s not a revisionist history. It’s looking at the past. It’s looking at the diversity of the past. It’s not trying to cherry pick stories to make us feel better. It’s quite the opposite. It’s saying here’s the traditional history that we are normally taught, this is what’s in the textbook, OK, we got that. Now, let’s talk about the various ways that we can challenge these histories. It’s allowing us to be honest with the past and the past to be honest with us about how we got to this place.

I have a video series and a podcast series, and I spoke to some really amazing American historical re-enactors who re-enact the life of enslaved people on plantations, mainly in the southern United States. And one of the people, Joe McGill, wants to save slave dwellings, so he called it the Slave Dwelling Project. Bringing these histories into the ways that the plantation is normally interpreted isn’t revising history, it’s actually being honest with what’s there. Those are the types of things that I want to bring into more classrooms, that I want to allow space for in more classrooms.

How common is it for pedagogical studies like yours to involve youth opinions?

Not as often as I or, I think, everyone would like. It’s difficult because of the ethics review. I worked with a lot of 15-year-old students, which means I needed the principal’s permission, the teacher’s permission, the parents’ permission and the student’s permission to talk to them for anything that was on the record. So that’s often a barrier. I think in the history education community, we need to spend more time talking with youth. And that’s why a lot of smaller projects are really great to allow for some of that.

But we often focus a lot more on teaching than we focus on learning. We focus on methods, and we don’t often focus on students’ experience. That’s one of the key things I wanted to be able to bring to this field with this book. We often don’t talk to youth who are failing. I spoke to students who were about to fail their Canadian history class, who already failed, who were taking it two or three times. What can we learn from their experiences, rather than just think they weren’t successful, they were just bored, they were just on their phones.

Have you received any feedback from the teachers whose work you criticized in the book?

I have been in contact with most of them, actually. And it’s been really interesting. It was 10 years ago that we first met, and the teachers are in a different place in their lives and in their understanding of who they are as teachers and their relationship with their students.

I think it’s important to remember that while we may engage with teaching behaviours that we might think were good and then see in hindsight that were not, it doesn’t mean we can’t become better. And in fact, this notion of striving to be better, striving to deconstruct our practices, is really important. It’s been a nice way to come back around and reflect with those teachers on this experience. I think it also helps that it’s been about 10 years.

I have also bumped into some of the students, and that’s been really great. First, they’re adults now. But to say to a student we weren’t sure was going to pass the course, “I just want you to know that I think about your voice and your opinions every single day. And I’m working on a project right now to honour that.” It’s been so lovely to be able to say that to them.

You mention in the book that you made a promise to a bunch of 15-year-olds. Did you tell them about the book back then?

It’s hard to explain to 15-year-old students what doctoral research is. So how we explained it is that this is research that could change what history education looks like. And one of the students in the focus group said, “That’s why I’m talking about this, because we could change how history’s taught. If anybody actually listens.”

And that phrase, “if anyone listens,” has haunted me, because it’s my responsibility to put words out there. Sure, somebody could read the dissertation. But I’m under no illusions that that’s going to make any sort of change. I always felt it was my responsibility to ensure that what those students shared with me were able to be shared with a larger audience.

For adults who have already gone through Canadian history education, what resources would you recommend to help critically re-engage with that history?

I would encourage them to first engage with different types of theories. Do a Google search of critical race theory or intersectional feminist theory, to see other ways of reading the world. Then I would encourage them to read or look at documentaries beyond what they normally gravitate towards, and to think about those things together. What are things I’m assuming here?

This is a lifelong project, a project of constantly thinking about “In what ways am I comfortable? What ways am I not comfortable?” And to always strive to be able to know when you are in a hall of mirrors and you’re reading, watching or listening to things that just reflect your own point of view. What are some other ways that we can engage in stories beyond ourselves? How could there be a different way of understanding this?

So often, you’ll hear something like “Slavery: in the past, people didn’t know that was wrong.” Well, who knew it was wrong? Enslaved people. So how are we understanding these particular narratives? Which ways are we getting trapped in them? It’s a willingness to be able to be in a greater relationship with the people around you, knowing that they don’t necessarily have the same experiences that you do.

This isn’t just a classroom project. I really think this book is good for anyone interested in questions about Canadian identity. ![]()

Read more: Rights + Justice, Education

Tyee Commenting Guidelines

Comments that violate guidelines risk being deleted, and violations may result in a temporary or permanent user ban. Maintain the spirit of good conversation to stay in the discussion.

*Please note The Tyee is not a forum for spreading misinformation about COVID-19, denying its existence or minimizing its risk to public health.

Do:

Do not: